Ghosts in the Vines

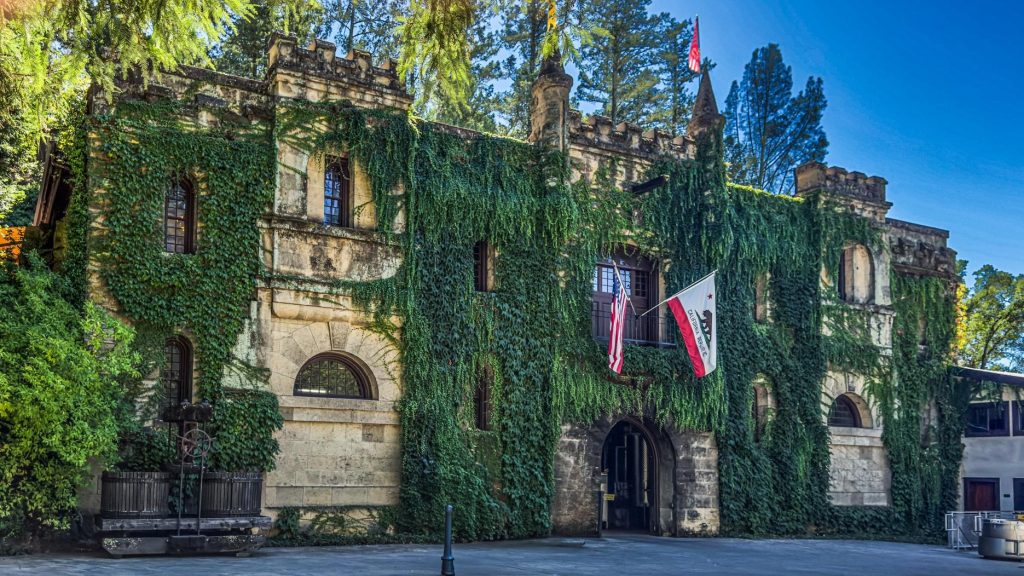

With Halloween right around the corner, it’s the perfect time to explore a spookier side of California—the ghost wineries of Napa Valley. The term “ghost winery” surfaced in Napa Valley in the late 1900s, when a new generation of vintners began uncovering abandoned stone cellars hidden beneath vines and ivy.

Their ghosts were not supernatural but historical—the echoes of men and women who built these cellars in the late 1800s, when California’s wine industry was growing like wild vines in summer.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, gold seekers heading north of San Francisco discovered fertile valleys ideal for grape growing. Many brought European winemaking traditions with them. In the early twentieth century, the Napa Valley boasted more than 700 wineries, winning international awards and expanding fast enough to rival Europe’s finest regions.

Then came the trials. Phylloxera—the root-destroying pest that ravaged Europe—struck California and wiped out roughly 80 percent of Napa’s vines by 1900. Just as the region began to recover, the nation enacted the 18th Amendment—the Volstead Act—kicking off what became known as Prohibition.

For fourteen years, the manufacture and sale of wine and other alcohol was outlawed. Only a few wineries survived, often by exploiting legal loopholes: Beaulieu Vineyard made sacramental wine for the Catholic Church; Beringer followed suit; Inglenook shipped grapes by mail order, with winking warnings not to let the juice ferment.

Bootleggers introduced a criminal element, often producing poor-quality, even dangerous wine mixed with chemicals. This era led to a massive decline in legitimate winemaking, forcing many family vineyards out of business.

By 1933, only 40 wineries were still standing. The rest were ghosts—stone shells scattered across the hillsides, reminders of what might have been. But Napa, ever resilient, rebuilt. Once the Volstead Act was repealed, vines were replanted, cellars reopened—and the region began its ascent into global prominence.

Chateau Montelena, built in 1882 and silenced by Prohibition, stunned the world nearly a century later when its Chardonnay won the 1976 Judgment of Paris. Far Niente, founded 1885 by John Benson and forgotten for fifty years, was rediscovered by Gil Nickel in the 1970s; its careful restoration ignited Napa’s fascination with preserving the past. Charles Krug—founded in 1861, purchased by Cesare Mondavi in 1943—became California’s first modern tasting room.

The new wave of winemakers — visionaries, romantics, and risk-takers — began unearthing many more of these ruins through the rest of the century. They found not just stone and timber, but stories: stories of those who came to the region with only a dream, some skills, and a piece of land, the ghosts of people who built the foundation for one of the wine world’s most successful legacies.

Ghost wineries have become symbols of Napa’s grand wine roots and renewal and proof that vines, like people, can return stronger after being nearly uprooted.