Some stories require no embellishment. This is such a story.

In 2018, a lifelong friend called Margaret Seidler to share concerns about a health risk she’d learned about on the DNA testing platform 23andMe. Seidler submitted her DNA to the site years previously, but didn’t think much of it. Her friend’s health scare worried Seidler, however, so she logged back in to look at her health markers.

That’s when her life changed.

Not because of any health prognostication.

“There was a message that had been sitting there waiting for me for over a year from cousins that I didn’t know about,” Seidler told Forbes.com. “The cousins had a picture, and it was obviously people of African descent.”

Seidler is white.

“I contacted my cousins and they wanted to know about their ancestry. I went back to my grandmother’s family Bible that I had had since 1983 and started looking up names of people I thought were in New York. It turns out that many of them had come (to Charleston, SC) 100 years earlier than I ever knew,” Seidler continues. “In service of my African American cousins out of St. Augustine, Florida, which is where they are, I found out that I was an eighth generation, not a fifth generation, Charlestonian, and had 100 years of slave traders in my family here in my hometown.”

Not dabblers in the slave trade, tycoons of the slave trade.

Seidler’s fourth great grandfather William Payne made a fortune as an auctioneer. Her research discovered he had, among other things, auctioned 9,268 enslaved human beings. Payne operated the largest auction house for enslaved people in Charleston.

“Shocked. Appalled,” Seidler explained of her emotions upon learning this. “I always thought because I was from a family near the east side that I had been exempt from all of what I had learned about slavery in Charleston. As I started researching, I was realizing that I was really from people who were quite wealthy here and in the thick of (the slave trade). They’d all lost their wealth after the Civil War.”

Mia S. McLeod

Not wanting to keep her family’s secret buried any longer, Seidler worked with researchers in Charleston to place a bronze historical marker at the site where her Payne family ancestors sold nearly 10,000 individuals into slavery.

“I thought I was going to feel better,” Seidler said.

She didn’t.

“I thought the burden was going to feel lifted, that I had uncovered truths that Charleston didn’t even realize in modern times,” she added.

It wasn’t.

Seidler wanted to apologize. Apologize to descendants of the people her family had enslaved and sold. She enlisted the services of South Carolina African American genealogy specialist Robin Foster. Seidler’s own research had found more than 1,100 newspaper advertisements for William Payne & Sons human auctions, surely, working with an expert, hundreds, if not thousands, of descendants could be found and apologized to.

It’s not that easy.

Slaveholders were clever and devious along with evil.

Slavers consciously, purposefully, obscured familial connections of the people they kept in bondage. They didn’t want them knowing their families. They didn’t want them to posses the strength of knowing who they came from. Enslaved people weren’t given last names. They were kept illiterate, by law. Slavers didn’t keep records of family lineages and the enslaved couldn’t do so.

By design.

In the eyes of slavers, the enslaved were property, like furniture, to be used and abused, not people, with parents and grandparents and siblings and cousins.

Seidler’s work with Foster revealed exactly one living descendant of the people her family enslaved: Mia S. McLeod.

State Senator Mia S. McLeod.

When Seidler sent an email to McLeod in 2020 expressing her desire to talk, McLeod had served 14 years in the South Carolina State House. The email came to the McLeod family funeral home which had been in business over 100 years.

“I didn’t know what this person wanted to share,” McLeod told Forbes.com. “She just said she had a family connection and I knew that my dad would want me to call her. So I did.”

McLeod’s father, the family’s historian, had recently passed.

“My dad always said you need to know your people and he’d tell us all the time you come from good stock,” McLeod remembers. “Now, when he said that as a child, I didn’t fully understand what that meant.”

Oddly enough, Seidler would help McLeod understand exactly what her father meant.

“Oh my goodness, I could not have anticipated the conversation that we had initially; it was such a long and thoughtful and engaging conversation,” McLeod said. “I had been through a lot personally and politically by that point and I just reached out to honor my dad. He would have wanted me to do that. I didn’t expect to go beyond that.”

McLeod and Seidler’s relationship has gone way beyond a single email and follow up phone call. The two have become connected, sharing their story.

On September 6 at the African American Research Library & Cultural Center, a branch of the Broward County Florida Library in Fort Lauderdale, the duo will tell their story again as the opening dialogue for “To Be Sold: Enslaved Labor and Slave Trading in the Antebellum South,” an exhibition on view at the AARLCC Gallery through December 27, 2025. The exhibit explores the brutal history of the domestic slave trade in the American South and the labor performed by enslaved Africans, primarily in South Carolina. Admission is free.

“I love Margaret. We have become family. When she called that day, we had such a heart-to-heart conversation, we talked about the fact that there was a connection, because our family’s name. We talked about my Morris family and our funeral home, and what my dad did know and what he shared with us before he passed away,” McLeod remembers. “I had no idea who (Seidler) was. She knew who I was, which is odd to me, because she lives in Charleston, and that’s a couple of hours away from Columbia, where I live.”

“To Be Sold”

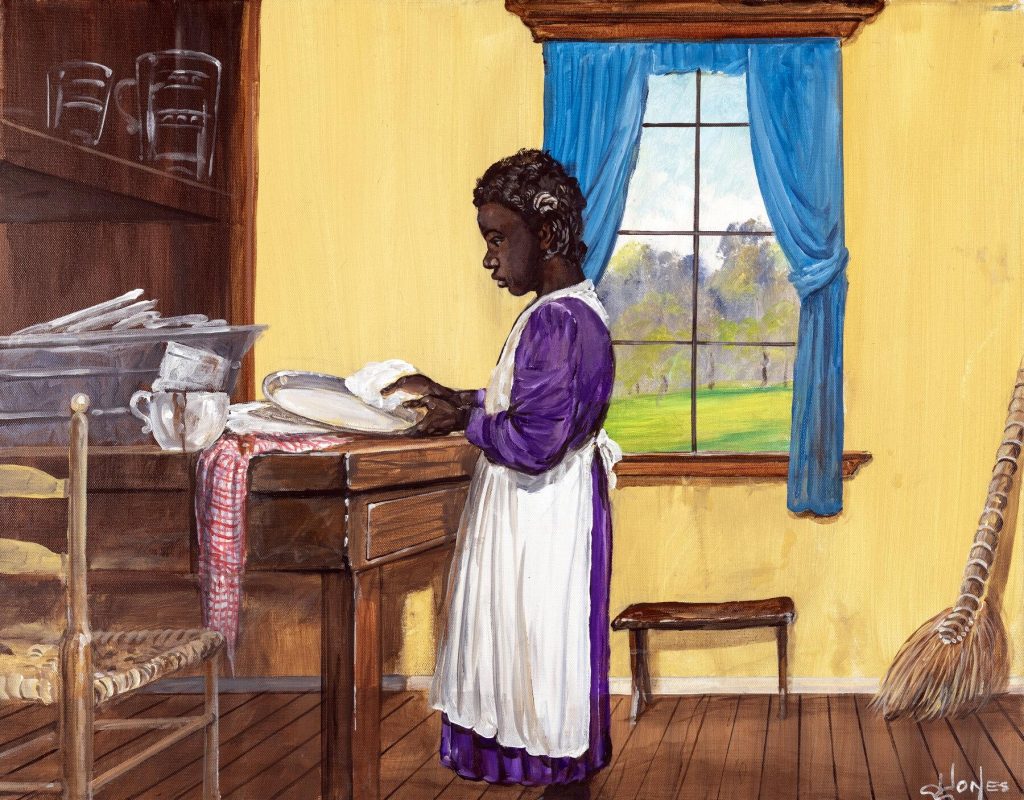

The Fort Lauderdale exhibition is inspired by Seidler’s book “Payne-ful Business: Charleston’s Journey to Truth.” Featured in the book and exhibition are artist John W. Jones’ haunting, historically accurate visual interpretations of the slave auction advertisements Seidler’s research uncovered. The combination of original documents and illustrations humanizes the history and legacy of slavery.

“All the paintings that you’ll see in Fort Lauderdale, they’ve all been vetted (and) very specific, little, tiny things had to be redone because we put a lot of research into the paintings,” Seidler said. “What we’ve learned in the last year and a half as this (exhibition) has been in South Carolina, is that the art–it’s the paintings that enable people who look like me to be able to go deeper into this whole subject of history that is not pleasant. (The paintings) humanize the people.”

The Broward County Library had a preexisting relationship with Jones, having presented his “Confederate Currency: The Color of Money” exhibition in 2021-2022.

Tameka Hobbs, Library Regional Manager for the African American Research Library and Cultural Center, was pitched on the Center hosting “To Be Sold.” She was open to the idea, even met Seidler, but she receives endless pitches to use the space.

“It wasn’t until I got the book that it really settled in my spirit,” Hobbs told Forbes.com. “I’m a historian by training, even though I work in the library, my research is on African American history, primarily 20th century, so I was familiar with these (enslaved auction) ads. To have Mr. Jones transform these into beautiful paintings, you vivify and understand that these are people, and more than that, you get a sense of how much labor, skill, intellect, ingenuity Black people contributed, not only to Charleston, but if you multiply this throughout the South–which was a huge economic engine for this country–when you understand that all of this talent was being exploited, that all of the profit that came from this work never enriched those individuals–their families got nothing–all of that taken together is heavy and necessary for us to continue to deal with.”

America was founded on slave labor and stolen land. The wealth and power the nation has been able to accumulate since emanates, directly, absolutely, from two great sins. The country’s original sins. Sins, without which, America would have in no way developed as it did.

“It’s interesting to see the energy that’s been put behind the Juneteenth holiday and all the celebrations and all the parties, but very rarely do you have the moments where people think about what it took to survive that experience for centuries and what was lost behind it,” Hobbs, whose ancestry, coincidentally, traces back to South Carolina, said. “In some ways, this (exhibition) is the other side of that coin, a necessary confrontation that we all need to have to remember this very, very important part of American history.”

Not everyone thinks this confrontation is necessary.

You Can’t Handle The Truth

On August 19, 2025, Donald Trump posted to social media chiding the Smithsonian Institution, and by extension all American history museums, that their treatment of America’s long history of slavery was overly focused on how bad it was. The blasphemy was consistent with a feature of Trump’s second reign: the regime’s immediate and unceasing support of white nationalism, white supremacy, and attacks on Black history.

“This is documentable fact. These are facts of American history that involve real people, and so it deserves to be talked about and discussed,” Hobbs said when asked her opinion of Trump’s post. “It was a major part of why the United States is what it is today, this economic success cannot be separated. You don’t get to pick the happy parts and leave out the other parts because they are connected. While there may be strong feelings, perhaps, of disdain against stories like this, I’m incredibly proud of my ancestors who survived these institutions and did what they needed to do in order for me to be where I am today and telling the story; continuing to keep the flame is the way that people like me can honor our ancestors and their struggle.”

Florida, where the exhibition is being staged, has been at the national vanguard of right-wing efforts to sanitize slavery, erase Black history, and give residents a phony-baloney, flag-waving retelling of American history. At the behest of Republican governor Ron DeSantis, Florida’s Department of Education approved in 2023 new American history guidelines that will “inform” students that some Black people benefitted by learning useful skills while enslaved.

From her time in the South Carolina legislature, McLeod has seen it all before.

“How intentional our policy makers, not just in my state, at a national level, to see the intention behind rolling back the rights and freedoms of Black people in particular, and to attempt to erase not only the history, the pain, the suffering, but the contributions and everything that my ancestors have worked so hard–my family has been in the state and contributing for at least seven generations,” McLeod said. “To serve in a legislature where the emphasis is on white people in general, and for them to not feel bad is the way it’s framed here. Nobody is concerned about the way I feel. Nobody is concerned about the way my ancestors felt. To have someone like Margaret, who doesn’t look like me, acknowledge that, and not only acknowledge that, but take action to enlighten, to engage, and to do better by everybody so that we can look at our shared history, our shared past, and move forward in a positive way. I hope that is what people gain when they hear us and when they see the exhibit.”

Like McLeod, Seidler is uniquely qualified to communicate her message of acknowledgement and reconciliation in an era where power welcomes neither. She’s worked in conflict resolution since the early 1990s, speaking at conferences. She wrote a book about leadership in 2008. She discusses her story every Thursday at two o’clock at the old slave mart in Charleston on Chalmers street.

“When I present, I don’t try and make people feel bad. I want them to feel open to what my experience has been, so that they can then take a risk,” she said. “If you go to page 107 in the book, that’s where the ask is. I never imagined this. I thought this was Charleston’s journey to truth, in fact, ‘Payne-ful Business’ is America’s journey to truth, because the people who were described in those paintings did the same sort of work up and down all of the colonies.”

Seidler wanted the truth, no matter how difficult or ugly it was for her family. Truth seeking, and truthfulness, are in short supply in America.

“As hard as it was to learn that Margaret’s ancestors enslaved mine, I can’t imagine not being able to talk about that and to really sit with that, understand that, gain clarity about it. Of course it’s painful for me and my family, it’s also painful for Margaret to know and to see and to discover the kind of damage that her ancestors did,” McLeod said. “She’s not responsible for that, and I think it’s important for us to acknowledge, as the first step, and then to take action. We can’t do that when we are being intentional about acting as if it didn’t happen and trying to erase what we know did happen and the way it happened and who’s responsible.”

No one living in America in 2025 is responsible for the nation’s history of slavery. Everyone living in America in 2025, however, is responsible for either acknowledging and working to repair the damage it created, damage continuing through the present day, or for erasing and obscuring that history and working towards re-entrenching the racial and labor power dynamics it enforced.