Imagine discovering that someone has not only stolen your identity, but used it to enroll in college, collect thousands of dollars in federal financial aid, and then vanished — leaving you to clean up the mess. This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. It’s happening thousands of times across America as fraudsters exploit weaknesses in the student aid system, turning what should be a pathway to education into a sophisticated criminal enterprise.

The numbers are staggering. In 2024, the Foothill-De Anza Community College District received roughly 26,000 applications, of which about 10,000 were flagged for possible fraud before the start of the quarter. Century College reported fraud rates comparable to those seen in the Foothill-De Anza Community College District. Minnesota’s Riverland Community College averaged more than 100 potentially fraudulent applications annually over the last two financial aid cycles. Most shocking, the College of Southern Nevada accumulated $7.43 million in debt during the Fall 2024 semester due to fraudulent student enrollments, money they were required to repay to the U.S. Department of Education.

These examples represent only a fraction of the many incidents reported in what has become a thriving underground economy built on stolen identities and federal student aid fraud.

The “Pell Runner” Playbook

The scheme is straightforward but highly effective. Fraudsters, often called “Pell runners” or “ghost students,” acquire stolen or synthetic identities from underground markets and use them to bypass college enrollment safeguards. Once admitted with the minimum required credit hours, they apply for federal financial aid, particularly Pell Grants designed to help low-income students.

The economics are attractive to criminals: at many community colleges, tuition costs are minimal or even waived. After covering these nominal fees, the remaining aid — potentially up to $7,400 per case — gets deposited directly into the fraudster’s bank account, ostensibly for living expenses. But instead of attending classes, these “ghost students” disappear once the funds arrive, often directing payouts to accounts opened with stolen identities at online banks, avoiding the risks of traditional brick-and-mortar transactions.

The Role of Social Media

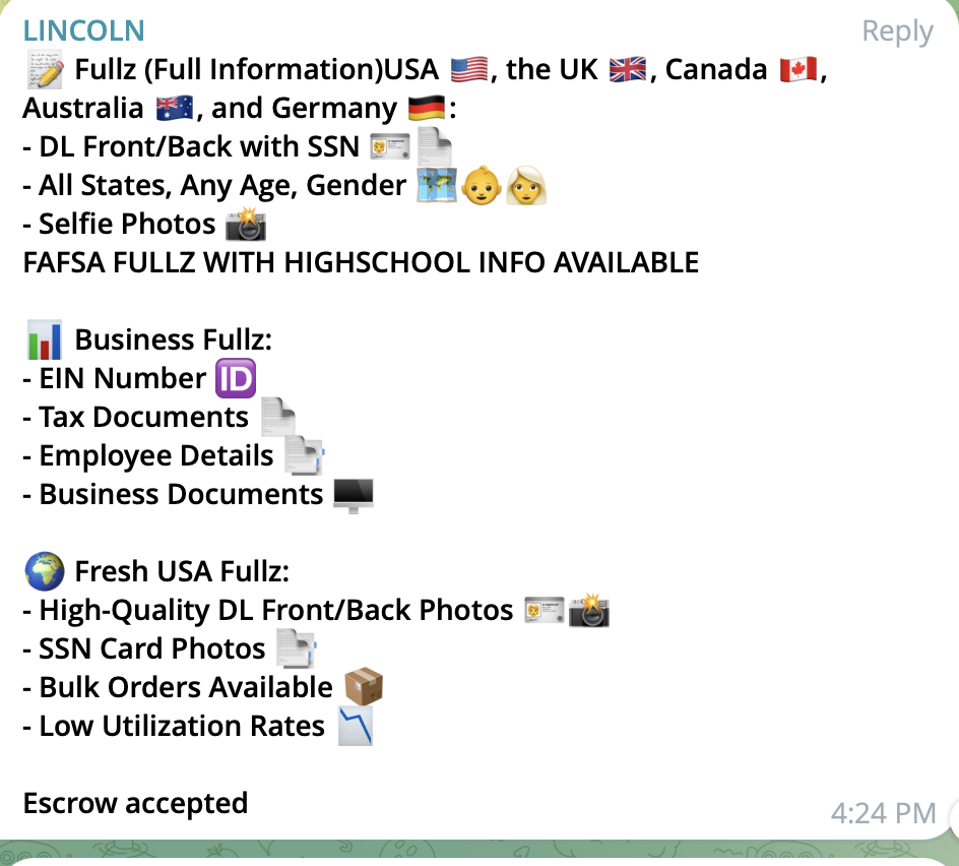

What makes today’s Free Application for Federal Student Aid (“FAFSA”) fraud particularly concerning is how social media platforms have become the infrastructure supporting these operations. On Facebook and Telegram, black-market vendors offer three key services that make student aid fraud accessible to virtually anyone.

First are “Fullz” — complete packages of stolen personal identifiers — ready to be used in fraudulent applications. Some sellers enhance these with stolen high school transcripts to make the paperwork look airtight. While some operations appear to be run from within the United States, others are clearly based abroad, demanding payment in foreign currencies for the stolen data they ship across borders.

The sophistication is escalating rapidly. Automated bots like “Monkey Express” now function as illicit e-commerce platforms, instantly delivering stolen identities tailored for fraudulent student aid applications. These bots advertise “fresh” profiles of young adults born between 1997 and 2006, the ideal demographic for passing institutional and federal verification checks.

Second are comprehensive tutorials sold for up to $300 that guide newcomers through the entire fraud process step-by-step. One tutorial I reviewed featured the identity of a 40-year-old Louisiana woman whose information has been circulating in criminal networks since 2021, used not just for student aid fraud but for renting apartments, opening bank accounts, and creating at least five synthetic identities.

Another tutorial featured a FAFSA submission confirmation summary, disclosed by the fraudster in a PDF file as proof of a successful application. The identity in this case belongs to a 60-year-old man from Idaho. Unlike the long-running pattern of abuse uncovered in the female victim’s case, my investigation shows that fraudsters only began exploiting this identity in 2024—and, so far, have used it just twice.

Third are specialized “cash-out services” that help fraudsters convert stolen funds into usable cash while concealing their tracks. In the fraud economy, stealing the money is only half the job—spending it without getting caught is the real challenge. Many scammers lack the tools, infrastructure, or contacts to move illicit funds safely, so they outsource the task. These operations advertise “college refund check” services and FAFSA withdrawal assistance, offering everything from ATM cashouts to cryptocurrency conversion.

One vendor’s advertising included a screenshot from a bank’s mobile disbursement portal, showing several historical check transactions sent to an address in California. My investigation into that address revealed a troubling pattern: it has been linked to multiple identity theft attempts, often during periods when the property was listed for sale. Notably, the fraudulent college refund checks appear to have been mailed there just after the home was sold—a strong indicator that the location is being exploited as a mule address.

From Ghost Enrollment to Enforcement: Securing the Student Aid System

The ripple effect extends far beyond individual victims. Higher education institutions, particularly community colleges, depend heavily on FAFSA funding for their operations budgets. Schools often build anticipated aid into their tuition and fee projections, using this predictable funding stream to secure financing for new facilities and expand high-demand programs.

Losing FAFSA funding can be devastating. Hampshire College in Massachusetts faced over $1 million in cuts to staff benefits and administrator salaries when FAFSA delays caused enrollment shortfalls. Saint Louis University delayed budget approval due to uncertainty around first-year enrollment and tuition revenue. Colorado institutions warned of simultaneous enrollment declines and budget instability due to FAFSA delays.

Recognition of the problem is driving new security measures. Beginning in summer 2025, first-time FAFSA applicants will be required to verify their identity with a government-issued photo ID, either in person or via live video. California’s Community College System has voted to require ID verification for all applicants statewide.

While these steps move in the right direction, they address only part of the challenge. Since sophisticated AI-driven tools allow fraudsters to defeat document verification methods, we must do more to leverage historical signals associated with identities during verification processes, making it harder for fraudsters to slip through institutional safeguards. The fight also requires direct efforts to disrupt the online fraud ecosystem itself — the social media marketplaces where stolen identities are packaged and sold, where tutorials teach newcomers the trade, and where specialized services help launder the proceeds. This means engaging directly with the leadership of social media platforms to explore rapid, effective methods for shutting down the thriving fraud markets operating in plain sight.

As the new academic year starts, the race is on between fraudsters perfecting their techniques and institutions strengthening their defenses. Millions of dollars in taxpayer funds and the educational opportunities of legitimate students hang in the balance.