By Ioannis Ioannou, Associate Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at London Business School

In parts of East Africa, AI tools are increasingly able to predict rainfall patterns, crop failure, and soil degradation. Satellite imagery and machine learning models inform planting schedules and flag pest risks early. These tools—developed by agritech startups and increasingly integrated into the procurement strategies of multinational agribusinesses—offer resilience through foresight. But while global firms adjust sourcing and hedge exposure, smallholder farmers—who produce around a third of the world’s food—often lack the means to act on the same insights. Irrigation, credit, and institutional support are scarce. Foresight is not the constraint. Capacity is.

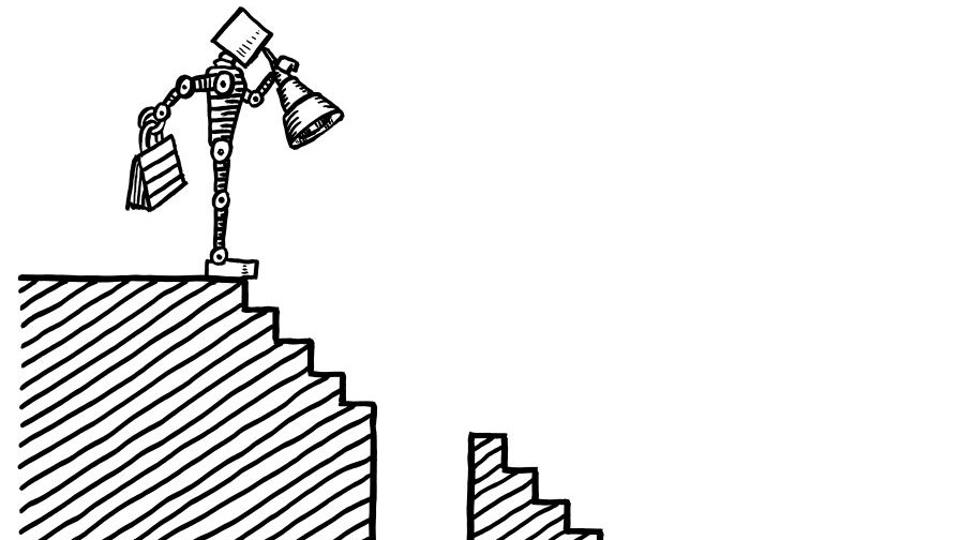

This asymmetry points to a deeper challenge: the growing gap between those who can anticipate disruption and those with the means to respond. Artificial intelligence is reshaping how we assess climate risk, optimise resource use, and navigate supply chain volatility. But it may also widen existing disparities—less by harming low-capacity actors directly than by accelerating the adaptive advantage of those already ahead. As foresight becomes central to sustainability strategy, the question shifts from who can see risk to who can act on it—and who is positioned to do so more effectively than others.

At the heart of this shift lies what I call the ‘foresight gap’: the widening distance between insight and agency. The issue is not data availability. Many actors—municipalities, farming cooperatives, suppliers—now have access to forecasts, dashboards, and models. The issue is that insight, in the absence of financing, technical tools, or enabling institutions, often leaves actors aware of risk but unable to manage it. The result is uneven resilience, where some accelerate while others struggle to keep pace.

AI could reinforce this pattern. Corporates with advanced modelling reconfigure procurement, redirect investment, and hedge operations. Suppliers in more vulnerable environments shoulder the consequences. Risk moves, but does not diminish. This is a form of selective adaptation: those with resources fortify their position, while others absorb the shock. Over time, this dynamic risks undermining both equity and stability. A transition that reallocates risk without building shared capacity creates fragility at the system level.

Agriculture illustrates this dynamic, but the pattern extends far beyond it. Cities with the means to invest in AI-integrated infrastructure planning are improving energy efficiency and emergency response. Others, particularly in the Global South, operate with outdated systems and limited technical capacity. In insurance, AI is reshaping climate risk pricing, pushing premiums upward or removing coverage in high-risk areas. And in supply chains, predictive analytics allow firms to reroute around disruption, while those at the frontline remain vulnerable.

These shifts introduce a systemic risk that is often underestimated. When only some actors adapt, the costs of disruption cascade across sectors and geographies. Fragility at the margins—among smallholders, subcontractors, or overstretched public agencies—can ripple outward. Consider the 2022 floods in Pakistan: extreme weather forced global retailers to shift orders and reroute logistics, but smaller suppliers faced months of operational paralysis and loss of income. Without adequate capacity to absorb shocks at every level, the system as a whole becomes more brittle. Concentrated resilience cannot ensure collective stability.

This reveals a core tension. AI is often promoted as a force for inclusion, but without governance aligned to that purpose, it risks doing the opposite. The foresight gap is not a glitch. It reflects underlying disparities in capital, capability, and institutional design. Without deliberate attention to how foresight is distributed—and how action is enabled—the gap will grow.

What does a just transition look like under these conditions? The conventional framing has focused on costs, benefits, and protections—especially for workers and communities. These remain important. But in the context of AI, justice must also mean access to adaptive capacity. The transition cannot depend solely on who already has the tools to respond. It must support others to acquire them. That is not only a matter of fairness. It is a condition for managing shared risk in a connected world.

This perspective has direct implications for institutions. First, we need investment in public foresight infrastructure. Predictive tools must be designed and deployed with broad usability in mind. That includes open-access climate models, data collaboratives, and analytics suited to under-resourced settings. National adaptation plans and resilience strategies should be grounded in intelligence that reflects real-world constraints. Crucially, this infrastructure must not remain siloed in ministries or multilateral organisations. It must be made accessible to those on the front lines of disruption—local governments, cooperatives, and civic organisations with the credibility to act and the trust to mobilise.

Second, we need AI-to-action partnerships. Companies using AI to manage their exposure should contribute to the adaptive capabilities of suppliers, contractors, and local communities. This is not a philanthropic gesture. It is a practical approach to reducing risk concentration across the value chain. Some firms are already exploring shared data platforms with suppliers or financing adaptation initiatives as part of broader ESG-linked targets. But these efforts remain isolated. What is needed is a shift in mindset—from risk extraction to risk co-management.

Third, we need to update our understanding of fiduciary responsibility. Boards and investors must ask whether AI-enabled strategies are building system-level resilience or simply reinforcing firm-level protection. Are companies redistributing risk across weaker links, or investing in broader capacity? These are strategic questions, not compliance matters. Fiduciary duty, in this context, should include attention to how foresight tools influence the allocation of risk—and whether they contribute to long-term value creation that is stable, inclusive, and credible.

It’s also worth acknowledging that AI is not only a predictive tool. Generative models and large language systems are increasingly shaping how knowledge is accessed, decisions are supported, and strategies are refined. These technologies may also expand forms of adaptive capacity, especially when designed for public benefit or integrated into frontline decision-making. But the existence of such potential does not negate the foresight gap. It changes its contours. As AI becomes more embedded in corporate strategy and public infrastructure, the question remains: who can use these tools meaningfully—and under what conditions?

The trajectory of AI in sustainability is not predetermined. It will reflect choices about governance, design, and accountability. The foresight gap is not a failure of technology—it is a challenge of institutional alignment.

AI is often assessed by its ability to predict, automate, or optimise. But in the context of sustainability, a different question matters more: does it support a transition that builds resilience across the system? Concentrated foresight without distributed capacity creates brittleness. Resilience must extend beyond the firm, the sector, or the region.

Those shaping AI’s role in the transition—corporate leaders, investors, regulators—are defining more than tools. They are shaping trajectories. The key issue is no longer whether AI can enhance foresight. That question has been settled. The real question is whether we align that foresight with the capacity to act—broadly, deliberately, and with urgency.

That is where leadership will be measured. Not by who saw risk first, but by who ensured others were ready when it arrived.

Ioannis Ioannou is an associate professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School. His research focuses on corporate sustainability and the strategic integration of ESG issues by companies and capital markets.