When I asked Amit Jain, the CEO of Luma Labs, what he was building, he didn’t say “a video generator.” He said a “universal imagination engine,” a studio-grade system that can produce coherent, emotionally resonant scenes from nothing but a prompt. “Directing becomes prompting,” he told me. “We’re trying to build tools that understand you like a really good DP would.”

Luma’s Ray 2 model, which builds on a lineage of NeRF-based rendering and physics-informed realism, can now produce short video clips with camera-aware motion and cinematic texture. The tools still aren’t easy to control and lack consistency, but they are improving at an astonishing rate. Generative AI models can rip off elaborate special effects without thinking about it, literally. Generative video is becoming its own medium.

Over the past six months, we’ve seen a wave of new models reach production quality at a remarkable pace, including Runway’s Gen-4, OpenAI’s Sora, Google’s Veo, Luma’s Ray 2, Pika 1.5, Kling, Higgsfield, and Minimax, to name just a few. More models are emerging every month. Some excel at animation. Others at live-action. Adobe’s Firefly and Moonvalley’s Marey are notably trained only on licensed media. Runway has a deal with Lionsgate.

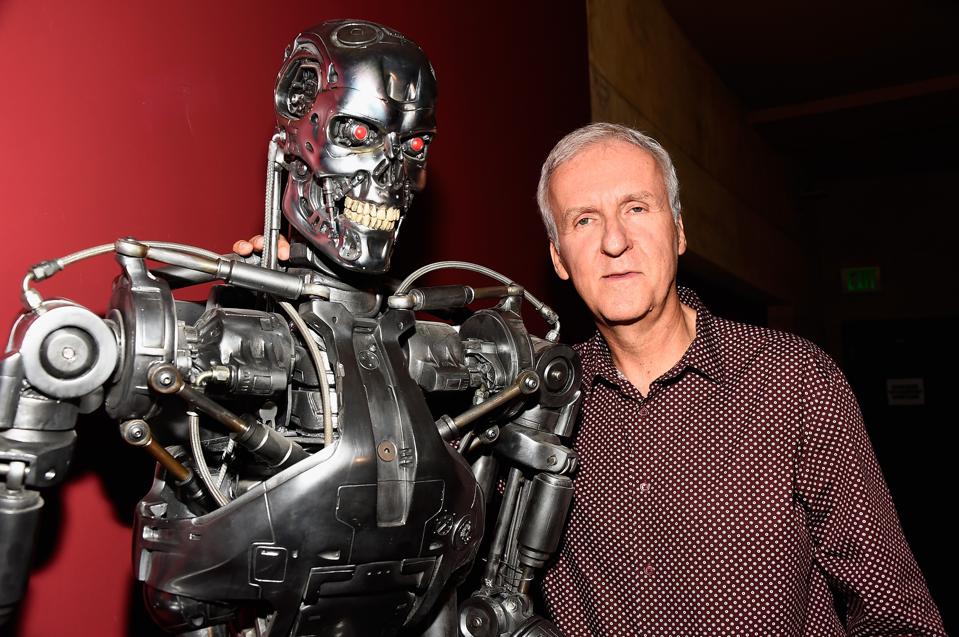

Blockbuster director James Cameron, who recently joined the board of Stability AI, says AI won’t eliminate jobs — but he knows better than most how long it takes and how much it costs to move atoms around in meatspace. The flight to AI will mirror the flight of physical production from Hollywood to cheaper locations, only this time, the locations aren’t real.

According to Bogdan Nesvit, founder and CEO of Holywater — whose AI-native streaming apps My Muse and My Drama have over 5 million downloads — “Ninety percent of our content will be AI-generated within two years.” Holywater is already using AI to produce short-form series for its own platform. Nesvit told me even his mother can no longer tell what’s synthetic and what’s filmed.

Holywater’s next move is a platform for TikTok stars, YouTube creators, and short-form filmmakers who want to work directly with AI-generated characters and sets. Nesvit describes it as “Hollywood in your room.” A director speaks aloud — “Wide shot. Morning light. Forest clearing.” — and the scene appears. Not as a sketch, but as a finished scene.

Film director Rob Minkoff (The Lion King, Stuart Little, Forbidden Kingdom, Haunted Mansion) offered a similar perspective at a Chapman University event two weeks ago, saying, “You’ll be directing in a virtual space the way you would direct on a soundstage — just faster, cheaper, and without the physical limits.”

At the Harvard XR Symposium, OpenAI researcher Jeff Bigham projected that “personalized generative video will become standard in entertainment within three years.” At the same event, Meta CTO Andrew Bosworth described a future where creators describe scenes and characters in natural language and watch them unfold instantly.

Entertainment executives are well aware of what’s coming. At a Bloomberg conference last fall, DreamWorks founder Jeffrey Katzenberg said, “AI will cut the cost of making animated movies by 90%.” Sony Pictures CEO Tony Vinciquerra echoed the sentiment, noting, “The biggest problem with making films today is the expense. We will be looking at ways to produce both films for theaters and television in a more efficient way, using AI primarily.”

Soon creators will be able to prompt fully navigable 3D virtual worlds with realistic physics and intelligent NPCs. Startups like Cecilia Chen’s Cybever and Li-Li Feng’s World Labs are already laying the groundwork. Chen told me recently on The AI/XR Podcast that Cybever’s goal is “to let creators generate entire virtual cities in real time, then walk through them and interact with AI agents as easily as building a deck in PowerPoint.”

This brings us back to Luma’s Jain. He’s not just talking about movies. We’re talking about filming dynamic avatars inside reactive 3D worlds — environments more like games than traditional films. Storytelling will evolve into storyliving, where games meet movies, like HBO’s Westworld, and we might start questioning who and what is real.

A new golden age of Hollywood is dawning, and as much as it pains me to say it, this golden age will come at enormous human cost. Hollywood isn’t alone. There’s no business that can’t be helped by massively cutting costs. Meaning, humans. Fortunately for many, the old ways fade slowly — but in our accelerated age, no one can say what “slowly” means anymore. The deeper threat to the entertainment industry remains the war for attention — and AI is arming the insurgents.

Hollywood can be understood as an ecosystem of capital, technology, IP, distribution, and celebrity. Celebrities will remain central. Studios will continue to own beloved IPs. But three of the studios’ advantages — capital, production, and distribution — are under siege and will inevitably fade in a world reordered by AI.

There’s much more to explore. In the coming weeks, I’ll publish a series of follow-up essays examining what this disruption could mean for Hollywood, gaming, big tech, and pop culture.