The launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) at the COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil underscores how the Amazon Forest can be part of the climate solution.

There’s another Amazon, of course: The river that gives the forest, and the whole region, its name.

The health and productivity of the Amazon Forest—and thus part of its ability to deliver climate solutions—is intertwined with that of the Amazon River and its tributaries. Yet the river basin itself, and therefore the whole intertwined system, is vulnerable to another intervention often offered as a climate solution: hydropower dams, which pose significant risks to both the river system and forest, including its ability to store carbon.

Here I’ll review these intertwined relationships and explore how diversified power systems can avoid or minimize negative impacts to the river-forest system and, moreover, how pro-actively conserving a connected and flowing Amazon River is itself a key part of climate solutions.

The word “Amazon” conjures up images of immensity (that immensity was the inspiration for the naming of the river’s massive namesake online retailer and technology company).

Stretching over 4,000 miles from its start in the Andes to the Atlantic, the Amazon is the world’s longest river (a title that is still up for debate, with many claiming the Nile is longer). But whether first or second, the river is long—as long as the drive from Chicago to San Francisco and back again.

Its drainage basin is indisputably the largest in the world: at 2.7 million square miles, it is nearly twice that of the Nile and close to the size of the lower 48 states. This scale gives rise to the Amazon Forest’s own superlatives: the river’s drainage basin is mostly rainforest, the largest one in the world, representing more than half the remaining area of rainforest on Earth.

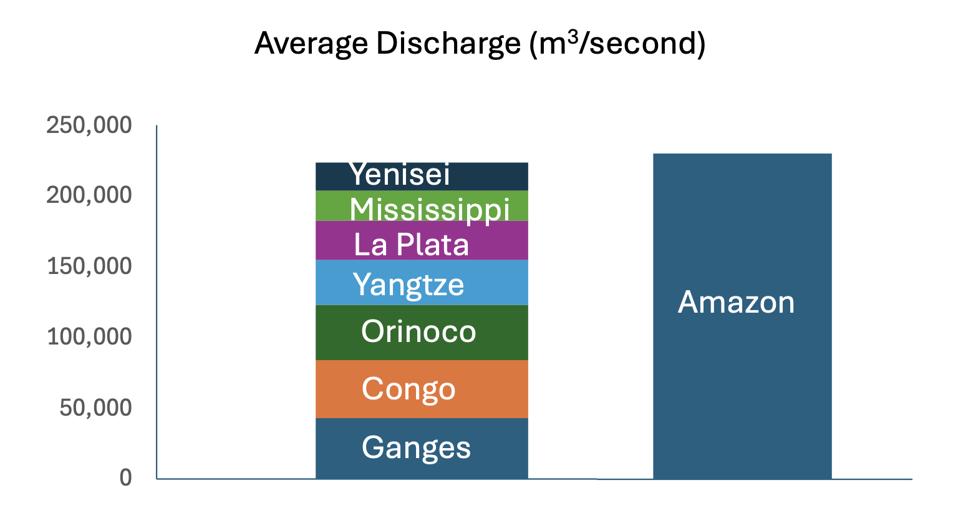

But what’s really amazing is the water: the volume carried by the Amazon is larger than that of the next seven largest independent rivers combined (independent meaning not a tributary to another river. Two of the Amazon’s tributaries, if they were their own river, would rank in the top 10).

The water is also what connects the river and forest. Precipitation falling anywhere in the basin must filter through the forest—its leaves, roots and soil—before flowing with gravity into streams, larger tributaries and then ultimately the Amazon proper.

Much of that precipitation arises from the forest itself. Water that doesn’t filter into streams remains in the soil, available for tree roots to draw up and then transpire through their leaves, a vertical pump working against gravity, connecting ground to sky.

Given the number of trees in the Amazon, there are effectively nearly half a trillion of these vertical pumps releasing 20 billion tons of water vapor into the atmosphere each day. They collectively feed the so-called “flying rivers” that deliver rainfall across South America—including all the way to Argentina—and are crucial for maintaining the continent’s agriculture and water supplies for people.

Deforestation disrupts this process, diminishing the flying rivers, regional rainfall, and ultimately river flows across the region. Thus, while the TFFF focuses on forests storing carbon, a healthy forest is also critical for maintaining the hydrological processes, from rain to river, across the Amazon Basin.

But the forest doesn’t just pump the water that fills the rivers. The rivers return the favor, nourishing key parts of the forest and sustaining vast and connected networks of peatlands and wetlands.

The Amazon and its tributaries aren’t simply flows of water, they are also flows of nutrients and sediment. Further, the Amazon and its tributaries aren’t confined to well-defined channels. During periods of high flow (about half the year), the rivers spread out across the forest. As they inundate their floodplains, the rivers deposit sediment, providing new sites for trees to grow, and nutrients, fertilizing the forest.

In large part due to the periodic flooding and fertilization, floodplain forests are among the most productive and diverse forests in the Amazon. Even though they represent about 14% of the forest, they are particularly valuable to biodiversity and store large amounts of carbon in their trees and soil, including peat – the goal of the TFFF.

But floodplain forests are at risk – from climate change but also from a commonly proposed solution for climate change.

Hydropower dams often generate debate because they can displace people and negatively impact river ecosystems, including migratory fish. However, hydropower dams—often proposed as a climate solution—also pose risks to floodplain forests’ ability to contribute to the climate solution of carbon sequestration.

First, dams generally regulate river flows in a way that reduces the extent and duration of inundation of floodplain forests, drying them out and making them more vulnerable to fire, a vulnerability already increasing due to climate-driven increases in air temperature and the frequency and severity of droughts.

Second, the reservoirs behind dams can trap the sediment and nutrients that the rivers carry. A study of six large proposed hydropower dams on major tributaries to the Amazon found that they would reduce sediment delivered to the whole Amazon basin by 64% and reduce phosphorous, a key nutrient, by 51%.

This loss of fertilization could further stress floodplain forests. A 2017 study found that floodplain forests could be an “Achilles’ heel of Amazonian forest resilience” because, when stressed and exposed to fire, “floodable forests [are] more likely to be trapped by repeated fires in an open vegetation state,” exacerbating risks of large-scale shifts from forest to savanna. This is what’s referred to as the Amazon “tipping point,” an abrupt shift with dire consequences that would be both a result of, and contributor to, climate change.

In other words, major changes to rivers, caused by hydropower dams, could destabilize vulnerable floodplain forests, increasing the probability of large-scale changes in vegetation that would undermine the forest’s ability to retain carbon – or even to remain forest.

Peru has committed to pursuing a low carbon electricity sector to meet its climate goals, and some large hydropower dams are under consideration on Amazon tributaries. However, because damming the rivers would stress floodplain forests, the climate solution of hydropower could undermine the climate solution of storing carbon in Amazon forests. It could also cause major negative impacts on migratory fish, which underpin a fishery that feeds millions of people and is valued at more than $400 million per year. Further, hydropower itself is vulnerable to climate change, with the Amazon offering a dramatic proof point of that vulnerability in recent years.

What can be done to avoid these significant tradeoffs?

Research from river basins around the world has demonstrated that countries can meet their renewable energy targets while avoiding hydropower dams with major negative impacts. This can be achieved through substitution of other renewables and batteries and innovations in grid management. Due to the “renewable revolution” – the dramatic decline in cost for solar, wind and batteries—these alternative pathways have become cost competitive.

At COP30, The Nature Conservancy and WWF announced initial analyses, prepared by the Brazilian energy consulting firm PSR, indicating that Peru has a wide range of viable options to meet its low-carbon power goals. These preliminary findings suggest that the country may be able to reach its targets even without building new hydropower dams in the Amazon (note that I contributed to this project).

The Amazon forest and river are intertwined, with the forest feeding water to the river and the river nourishing the forest with sediment and nutrients. By storing carbon, the forest can be a key part of climate solutions but plans for expanding hydropower to meet climate targets could undermine that climate solution.

Fortunately, alternatives that avoid hydropower are now realistic and cost competitive. Countries like Peru can pursue their climate targets while maintaining the health of both Amazons, river and forest.