Today is World AIDS Day, and it is still hard to describe what was really lost in the AIDS pandemic. I can point to statistics, but they only tell us how many people died. They cannot show the world that would have existed, the futures, the leaders, the friendships, and the masterpieces that never came to fruition.

In West Hollywood, a new AIDS memorial is outside the WeHo Library, just yards from the nightlife district the city has been known for. The monument asks that passersby stop and listen to stories that too often go untold. It tries to do something almost impossible: to capture not only how people died, but how those same people lived and loved, and what they might have given the world if they had grown old enough to comb gray hair, as old folks used to say.

Fran Lebowitz, in a clip that’s been in heavy rotation, says that one of the things AIDS took from us was an audience of connoisseurs. These were talented, beautiful people who loved opera, Broadway, books, and art so intensely that their absence has lowered the standard for everyone around them. As Lebowitz says, it was often the most talented who were taken the swiftest. On days like this, the grief is not only for the artists and thinkers who died, but for all the people whose passionate attention made culture sharper, stranger, more demanding. AIDS took not only the performers but also the critics, mentors, fans, and the prickly, opinionated queens who would have insisted that we do better.

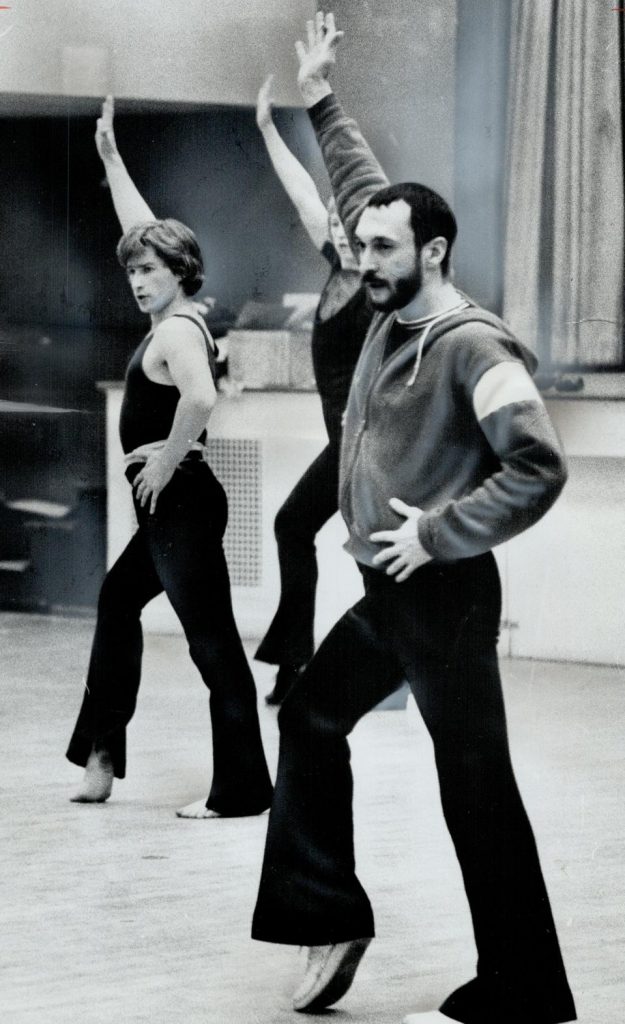

Some of those people have become names in history, but they were once living, working people whose influence still lives. One person I think of often is Michael Bennett. Bennett directed and choreographed “A Chorus Line” and “Dreamgirls.” He is as responsible for modern musical theater as Stephen Sondheim or Andrew Lloyd Webber—and maybe we wouldn’t have had to endure quite so many Webber shows if a talent like Bennett had lived. In my late teens, I was mesmerized by “A Chorus Line,” and years later, thanks to YouTube, I fell in love with his wildly inventive “Turkey Lurkey Time” choreography, all that dancing in impossibly high heels. If one man could do that much by his mid‑forties, what might he have created in the 1990s, and who might he have mentored if AIDS had not cut his life short?

Willi Smith, whose WilliWear line I started wearing in high school, was another kind of visionary loss. His clothes were playful, accessible, and modern; they made it feel possible for a Black kid to be stylish on his own terms. Smith’s brand was just crossing into mainstream acceptance when he died

of AIDS‑related illness, shutting down not only his own career but a whole branch of Black fashion that might have grown from his example. Where would Rudolf Nureyev have taken dance? Where would Keith Haring’s public, hypergraphic art be now? How many more singers would Sylvester, who wrote unapologetically queer disco anthems and mentored voices like Martha Wash, have given a chance? And there is Max Robinson, the first Black anchor of a network evening news program. He did everything Peter Jennings did, while being Black.

When people talk about AIDS as if it were in the past, they ignore Black people. In the United States and its territories, Black Americans made up roughly 42% of the nearly 38,000 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, even though Black people are only about 13% of the population. Black people are still several times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than white people, more than three decades after the virus first entered public consciousness.

About 31% of the new diagnoses in 2018 were among Black men and 11% among Black women, and among Black adult and adolescent women, the vast majority of new diagnoses, nine out of ten, were attributed to heterosexual contact. In other words, the story the culture tells about HIV as a gay white man’s disease doesn’t track with the actual epidemiology. Black women who have never had sex with another woman, Black men who have never set foot in a gay bar, Black trans women navigating stigma and criminalization: all of them live in the blast radius of an epidemic that has more to do with racism than with anyone’s individual choice.

Since the turn of this century, well over 100,000 Black people in the United States have died of HIV‑related causes. Black communities bear a disproportionate share of new infections and deaths. I imagine a city the size of Annapolis, Maryland; Athens, Georgia; or St. Augustine, Florida simply erased from the map. That is what HIV has done to Black life in this country. On bad days, when I feel sorry for myself for being single at fifty, I remember that many of my potential lovers, friends, elders, and mentees never had the chance to grow old enough to swipe right on anyone.

When I was a freshman at Boston University in the early 1990s, I lived on what everyone simply called “the gay floor.” It wasn’t intentional, just the random luck of the housing lottery that put a dozen queer kids on my floors, not including several of us who were still closeted. The dorm was near Boston’s Kenmore Square and the Fens, which were gathering places for alternative and queer kids. This was before Grindr or chatrooms, and word spread that our floor was a kind of safe space.

A Latino club kid who was visiting, not a student, came back to the dorm after being diagnosed with HIV. It was winter, and he stood there in a cutoff T‑shirt and cutoff jean shorts. What I will never forget is the hours he spent wailing and crying in the bathroom. It’s hard to overstate the fear. College is a time of sexual experimentation. Like many queer kids then, I associated sex with death—and I wasn’t wrong to. My junior year, 1995, saw the largest number of HIV/AIDS‑related deaths. That young man who was convinced he was going to die wasn’t wrong to be terrified.

During the pandemic, a dear friend of mine received his own HIV diagnosis. His sex education came mostly from the internet. Growing up in a part of Nevada that isn’t Vegas, his understanding of AIDS and gay sex was elementary. By then, treatment was far better, and HIV was no longer an automatic death sentence. There was even PrEP, a daily medication that prevents HIV infection by stopping the virus from taking hold in the body. He didn’t know about PrEP, which came out in 2012. The epidemic still infects people who have been given too little information and too few tools.

No one loves a gay Black man more than a lesbian. That is a joke I tell, but it is also a kind of truth. So many of my lesbian friends carry the scars of that first, brutal wave of the epidemic; they can name dozens of men they nursed, buried, and still dream about. It has been lesbian women who have educated me most about the sheer devastation of those years, about what it meant to spend your twenties and thirties moving from hospital visits to memorial services to political meetings.

Long before “ally” became a word we printed on T‑shirts, lesbians were organizing blood drives and fundraisers, cooking meals, and tending to bodies that families refused to touch. They did this for men who often rejected them from gay male spaces. Black women artists like Sheryl Lee Ralph, Dionne Warwick, and Tina Turner stepped into that breach. When corporate sponsors were nowhere to be found, Sheryl Lee Ralph used her fame and, importantly, her own money to raise money and awareness. Sheryl Lee Ralph’s feet should never touch the ground in any gayborhood. Ralph has spent decades leveraging her career to fight HIV and AIDS, a reminder that Black women are rarely allowed to be just artists; they are drafted into the role of civil rights leaders whether they ask for it or not. On World AIDS Day, it is important to remember that the story of this epidemic is not only about those who died, but also about the women who were told to save everyone else.

For all the horror and neglect, there has also been something close to a medical miracle. Because of the work of activists, treatment for HIV has become more effective, more tolerable, and more widely available than anyone in the early 1980s could have imagined. Today, PrEP is delivered to my doorstep. The first time I saw that UPS envelope, I wept. That envelope is the direct result of ACT UP die‑ins, of Elizabeth Taylor browbeating politicians and donors, of Sheryl Lee Ralph hosting fundraisers, of Black and brown communities demanding to be included in clinical trials.

Globally, programs like PEPFAR and agencies like UNAIDS have transformed HIV from an almost certain death sentence into a chronic, manageable condition for millions of people. That success belongs to activists in the Global South as much as to anyone in D.C., and it’s one of the few clear moral achievements of the George W. Bush era. Which is why it is so infuriating to watch that progress being chipped away by politics and denial.

During the Trump administration, cuts and threats to foreign aid and global health funding put pressure on the very programs that could end AIDS as we know it, especially in the poorest countries. At the same time, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now Secretary of Health and Human Services, is questioning the basic scientific consensus that HIV causes AIDS. These are not harmless eccentricities. When powerful people dismiss science or defund prevention, infections that could have been prevented happen instead. Under the current administration, even the basic promise that PrEP will remain free or low-cost is in doubt. A Supreme Court case and deep federal cuts to HIV prevention and research could let officials weaken no‑cost coverage and limit who can get PrEP, undoing hard‑won progress for the communities most at risk.

What makes this World AIDS Day scary is that there will be people diagnosed today, even though it does not have to happen. There are tools: condoms, clean needles, PrEP, PEP, and effective treatment that makes the virus undetectable and therefore untransmittable. The thing is, access is uneven, education is patchy, and stigma is stubborn.

So when I walk through the AIDS memorial in West Hollywood, I am not only walking through history; it’s a warning. The names and stories of the monument stand beside the names we will never learn. They also stand beside the people who are being diagnosed right now, in cities and towns that will never build a monument to them.

On this World AIDS Day, grief and gratitude sit side by side. It’s grief for Michael Bennett, Max Robinson, Keith Haring, Willi Smith, Sylvester, the club kid in cutoffs, my friends, and the quarter‑million Black people whose absence has reshaped Black culture. It’s gratitude for the lesbians, the Black women, the artists, the activists, and the scientists who refused to be silent. The stories in that West Hollywood monument, and in my own memory, are not just about how people died. It’s a monument to a world that never came to be.