Most people I talk to haven’t been educated on the difference between Roth IRA vs Taxable Account vs IRA. This is especially true with taxable accounts. Many investors are only familiar with the “tax me now” or “tax me in the future” simplified explanation of these tax advantaged retirement accounts. Many people find themselves during their working years debating over the flexibility of the use of taxable accounts versus the restrictions of Roth IRA and IRA accounts.

Rather than discuss the rules around savings of Roth and IRA, this article highlights the taxation of having a substantial $500,000 investment balance. But which account that $500,000 lives in: taxable brokerage, traditional IRA, or Roth IRA, can change your future spending power by hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In this article, I’ll walk through how a globally diversified 60% stock/40% bond portfolio can finish in very different places depending on account type and filing status. We’ll contrast:

- Married filing jointly vs. single

- All domiciled in Illinois

- All earning $200,000 of household income

- All starting with $500,000 invested 60% in MSCI ACWI and 40% in Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond (AGG)

We’ll use today’s (2025) federal and Illinois tax rules as a guide, plus simplifying assumptions to keep the math readable.) Along the way I’ll point you to IRS guidance and other resources, and connect this article to my earlier Forbes work that focused more on the savings and systematic withdrawals on Roth vs. traditional vs. taxable investing. (Forbes)

Roth IRA Vs Taxable Account Vs IRA refresher

Before we talk tax impact, let’s highlight how each account type gets taxed.

1. Taxable brokerage account

- You invest after-tax dollars.

- Interest (from the bond side of the portfolio) is taxed every year as ordinary income.

- Qualified dividends (mostly from global stocks in ACWI) get the lower long-term capital gains rates if you meet the holding rules.

- Unrealized gains are not taxed until you sell, then they’re taxed at long-term capital gains rates.

- Illinois taxes all of this as regular income at a flat 4.95%.

2. Traditional IRA

- Contributions assumed to be deductible (we’ll focus on the growth phase here).

- The money grows tax-deferred.

- Withdrawals in retirement are taxed as ordinary income at federal rates plus Illinois’ flat rate. (IRS)

3. Roth IRA

- Contributions are made with after-tax dollars. I refer to this as “from your checkbook”.

- Growth is tax-free if you follow the Roth rules (age 59½ and 5-year rule).

- Qualified withdrawals in retirement do not increase your taxable income.

Roth IRA Vs taxable account Vs IRA assumptions

Our investment and tax assumptions (so you can sanity-check the math)

Portfolio assumptions

- Starting balance: $500,000

- Time horizon: 10 years (think a 40-something Gen Xer or a 35-year-old Millennial looking out to retirement).

- Allocation: 60% MSCI All Country World Index ACWI (global stocks) / 40% Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond (AGG-style core bonds). (MSCI)

- Expected average annual pre-tax return: 6.5%

- This is roughly in the middle of the long-term range often used for diversified 60/40 portfolios.

- Income vs. growth split:

- Stocks: ~2% qualified dividend yield

- Bonds: ~3% ordinary interest

- Weighted portfolio yield ≈ 2.4% per year; the rest of the 6.5% (about 4.1%) shows up as price appreciation.

Tax assumptions

I use 2025 tax brackets as a proxy for long-run planning.

- Household income: $200,000

- Domicile: Illinois (flat 4.95% state income tax).

Federal marginal rates on ordinary income (wages, bond interest, IRA withdrawals):

- Married filing jointly (MFJ): $200,000 falls in the 22% bracket.

- Single: $200,000 falls in the 32% bracket.

Federal tax on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends:

- At $200,000 of income, both single and MFJ fall squarely in the 15% long-term capital gains/qualified dividend bracket. (IRS)

Net rates we’ll use (federal + Illinois):

- Ordinary income, MFJ: 22% + 4.95% ≈ 26.95%

- Ordinary income, Single: 32% + 4.95% ≈ 36.95%

- Qualified dividends & long-term capital gains, both statuses: 15% + 4.95% ≈ 19.95%

Additional assumptions:

- Assume buy-and-hold (no trading) in the taxable account.

- Ignore the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax to keep the illustration simple.

- Assume the entire account is liquidated in one year at the end of 10 years.

- Use the current bracket as a stand-in for your retirement bracket for traditional IRA withdrawals (a simplifying assumption; in real life we’d model your retirement income separately).

Roth IRA vs taxable vs IRA growth illustrated

- Starting balance: $500,000

- Time horizon: 10 years

- Portfolio: 60% global stocks (ACWI-style) / 40% core bonds (AGG-style)

- Expected pre-tax return: 6.5% per year

- 2.4% as income (≈1.2% bond interest, 1.2% qualified dividends)

- 4.1% as price appreciation

- Income: $200,000 household, Illinois residents

- Filing statuses: Married Filing Jointly (MFJ) vs Single

- Taxation (same as before):

- Ordinary income (bonds, traditional IRA withdrawals – but we will not tax withdrawals in this 10-year illustration)

- MFJ: ~22% federal + 4.95% IL ≈ 26.95%

- Single: ~32% federal + 4.95% IL ≈ 36.95%

- Qualified dividends & long-term capital gains (taxable account and final sale):

- 15% federal + 4.95% IL ≈ 19.95%

- Ordinary income (bonds, traditional IRA withdrawals – but we will not tax withdrawals in this 10-year illustration)

For this 10-year pass, we:

- Still tax annual interest and dividends in the taxable account.

- Still tax final capital gains in the taxable account at year 10.

- Do not tax any withdrawals from the traditional IRA at the end of 10 years. We treat its ending value as pre-tax, just like the Roth’s is tax-free.

Step 1: Ten years of tax-free compounding (Roth & traditional IRA)

First, ignore all taxes on growth and just let the $500,000 compound for 10 years at 6.5%:

Roth IRA / traditional IRA 10-year value: ≈ $939,000

- In a Roth IRA, that ≈ $939,000 is tax-free (assuming Roth rules are met).

- In a traditional IRA, that ≈ $939,000 is pre-tax value. In real life, you’d owe ordinary income tax when you withdraw.

Both grew at the full 6.5% without any tax drag during the accumulation period.

Step 2: Ten years of growth in a taxable account

The taxable account is where the tax drag shows up. Each year, we assume:

- Bond interest (1.2% of the portfolio) is taxed at the household’s ordinary income rate.

- Qualified dividends (1.2% of the portfolio) are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate.

- The after-tax income is reinvested, adding to cost basis.

- The remaining 4.1% shows up as unrealized price appreciation (no tax until you sell).

- At the end of year 10, you sell the entire position:

- You pay 19.95% on the unrealized capital gain.

- You’re left with an after-tax final value.

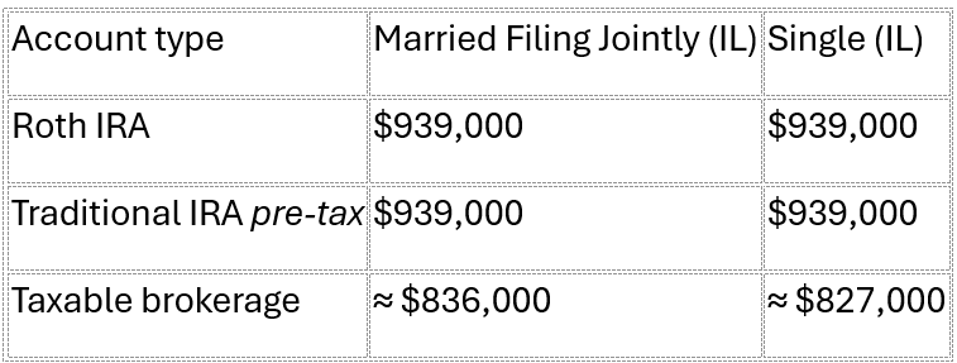

Ten-Year Ending Balances (After Tax)

1. Roth vs traditional (under these assumptions):

- Because we’re not modeling taxes on traditional IRA withdrawals, Roth and traditional look the same numerically over 10 years—both end at about $939,000. The real-world difference is that:

- Roth is truly spendable without future tax.

- Traditional is pre-tax, and withdrawals will eventually be taxed at ordinary income rates.

2. Taxable accounts lag IRA/Roth IRA over a shorter period, but still by a meaningful amount.

- MFJ taxable: ≈ $836,000

- Single taxable: ≈ $827,000

- About $103,000 for the married couple

- About $112,000 for the single filer

3. Effective after-tax return in taxable accounts.

Over 10 years, those ending values correspond to roughly:

- Roth / traditional IRA: full 6.5% annualized (no tax drag on growth)

- MFJ taxable: ≈ 5.3% after tax

- Single taxable: ≈ 5.2% after tax

Compared to the ≈ $939,000 in an IRA, the tax drag over 10 years knocks off:

- Even over “just” a decade, that 1.2–1.3 percentage point gap between 6.5% and ~5.2–5.3% adds up to six figures on $500,000.

Step 3: The tax bills inside the 10-year taxable account

If you want a bit more color to narrate in your Forbes draft, here’s what happens inside the taxable account over those 10 years:

- Married Filing Jointly (IL)

- Total tax paid on annual income (interest + dividends) plus final capital gain tax: ≈ $91,000

- After-tax final value: ≈ $836,000

- Single (IL)

- Total tax paid over 10 years: ≈ $98,000

- After-tax final value: ≈ $827,000

Because the Single filer faces a higher ordinary income rate, they:

- Pay more tax on the bond interest portion each year.

- End up with a slightly lower after-tax balance than the married couple, even though the starting amount, investment mix, and pre-tax return are the same.

Taxable accounts should be used wisely

Taxable accounts have their place. This article is meant to highlight the tax issues. As they are not tied to IRS retirement rules, they are the most flexible. To make them more tax-efficient:

- Tilt bonds toward IRAs (especially traditional IRAs) and keep more stocks in taxable accounts.

- Favor low-turnover index funds or ETFs that don’t spit out large capital-gain distributions.

- Use tax-loss harvesting in down years to offset gains. (Forbes)

When used well, taxable accounts can complement Roth and traditional IRAs, not compete with them.

Pulling it together: Roth IRA vs Taxable Account vs IRA

Here’s how I’d summarize the $500,000 case study:

1. Same investments, very different outcomes.

A 10-year 60/40 investment compounding at 6.5% can finish at:

- ≈ $939,000 in a Roth IRA (both married and single). This money will not be taxed during your retirement years after 59 ½.

- ≈ $939,000 in a traditional IRA (both married and single). This money will be federally taxed at your then prevailing tax rate. Illinois residents currently will are not taxed.

- ≈ $836,000 (MFJ) or $827,000 (Single) in taxable

2. Single filers face a steeper hill than married couples at the same income.

Higher ordinary income brackets for singles mean more tax drag on bond interest and steeper future taxes on traditional IRA withdrawals.

3. Tax diversification matters.

Having money in all three “buckets”—Roth, traditional, and taxable—gives you more levers to pull in retirement. This theme shows up across my Forbes work on Roth vs. traditional IRAs and brokerage accounts, and it plays out clearly in the numbers here.(Forbes)

Next steps in your Roth IRA vs taxable account vs IRA journey

This article is meant as education, not individualized tax advice to highlight how taxable accounts are taxed. By the way, if you have short term certificates of deposit and money market accounts they are taxed like taxable brokerage accounts.

How you should save in the future depends on the specifics of your situation. It is not how much you make, it is how much you keep after taxes. Your investing strategy isn’t just picking investments; you’re designing the tax shape of your retirement.

I recommend reaching out to a fiduciary, Certified Financial Planner who takes both investment and tax planning seriously. Tax planning is part of the curriculum that Certified Financial Planner’s (CFP) must show competence in to earn the CFP credential. You owe it to yourself to find someone who can help you make the right decisions for you when it comes to Roth IRA vs Taxable Account vs IRA.