Between the late 1970s and the mid-1980s, the Cars were one of the most popular bands in rock. With an original sound that blended classic rock, sleek New Wave and catchy pop, the Boston-based group — singer/rhythm guitarist Ric Ocasek, singer/bassist Benjamin Orr, lead guitarist Elliot Easton, keyboardist Greg Hawkes and drummer David Robinson – recorded multiplatinum albums and many memorable hit singles including “Just What I Needed,” “My Best Friend’s Girl,” “Let’s Go,” “Shake It Up,” “You Might Think” and “Drive.”

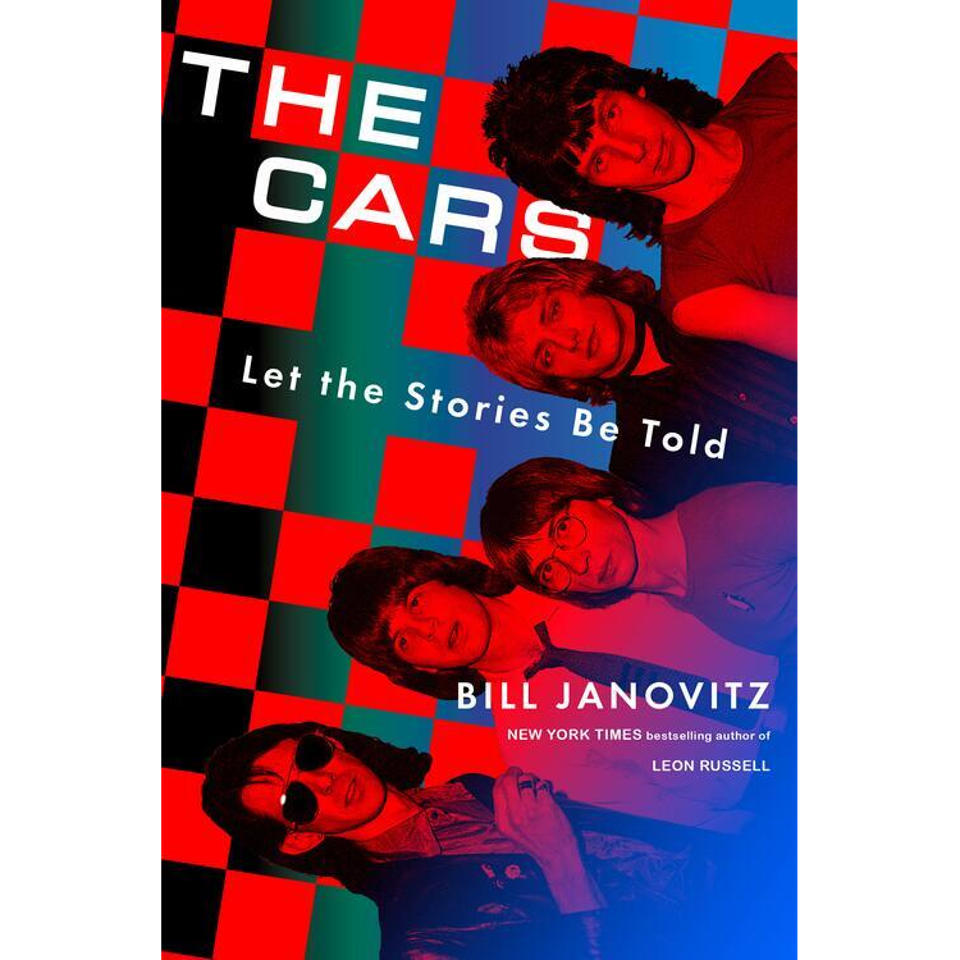

And despite the Cars’ commercial success during their peak period, and their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame decades later, not much is truly known about the band outside of music (except perhaps Ocasek’s marriage to model Paulina Porizkova and Orr’s death in 2000). That had been the mystery until the recent publication of The Cars: Let the Stories Be Told, a superb 500-page biography by Bill Janovitz, the singer and guitarist for the alternative rock trio Buffalo Tom.

Drawing from new conversations with surviving members Hawkes, Robinson and Easton and archival interviews with Ocasek and Orr, as well as reminsices from longtime associates and friends, Let the Stories Be Told is the definitive history of the band: from Ocasek and Orr’s earliest collaborations as members of the bands Milkwood and Cap’n Swing in the early 1970s; to the Cars’ growing popularity in the Boston music scene leading to the recording of their 1978 debut album; through their commercial ascension and the tensions that led to their breakup in the late 1980s; to finally their reunion in 2011 and the death of Ocasek, the group’s chief songwriter and driving force, in 2019.

“I knew going into it that this was going to be a story about a band, not just sort of one guy who happened to have these other guys behind him,” says Janovitz, whose introduction to the Cars’ music occurred when he was about 12 years old. “This was a real band from start to finish. It was always the same five members. And even after Ben passed and they had the reunion in 2011 and made that record [Move Like This], they didn’t get a substitute bass player to go on the road with them. So it really was a band at heart.”

Janovitz — whose previous music books include Rocks Off: 50 Tracks That Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones and Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History — had the idea of writing about the Cars after performing with Easton at a Wild Honey benefit concert in 2019. At the time, Ocasek was still living. “I don’t know if Ric would have been open to having a book done, period,” Janovitz recalls. “But if it was going to be done, it wasn’t going to be with Bill Janovitz.” It was after Ocasek’s death that the project resumed with Easton, Hawkes and Robinson on board. “I think they were happy to be able to sort of tell their story freely,” Janovitz says. “I don’t think they would have felt as free to tell that story had he still been around.”

There were things that Janovitz learned or rediscovered about the Cars while working on Let the Stories Be Told. “I knew that Ric wrote all the songs, and then the disagreements and interpretations of what that really entails,” he says. “None of it’s shocking for anybody who’s been in a band. But I don’t know if I knew that. I don’t think as a kid I knew that there were necessarily two singers [Orr and Ocasek]. But I knew I would get a greater appreciation for some of the records like Heartbeat City that I didn’t really necessarily love from start to finish [when I was 16-17], and the depths of their contributions.”

The book documents the band’s remarkable rise in a short period of time after their formation in 1976, from being regulars at Boston’s Rat club to them signing with Elektra Records. Outside of Robinson, who had played in the Modern Lovers, the members of the Cars were relative unknowns. “From getting David Robinson as their drummer to recording their debut album in London, it’s like less than a year with [producer] Roy Thomas Baker, who’s coming off the heels of Journey and Queen,” the author says. “And it’s like this heady whirlwind. They were starving the year before. And things finally hit it. Their record comes out in June [1978]. It’s gold by October and platinum by December. To this day, they refer to that first album as their Greatest Hits album.”

Let the Stories Be Told also traces the relationship between Orr and Ocasek, whose musical partnership goes back about 10 years before the formation of the Cars. “It’s an interesting dynamic,” Janovitz says. “They were like definitely musical partners. They were friends. But a lot of it’s still shrouded in mystery. They were definitely these sorts of yin-and-yang-type brothers, partners. They spent so much time together… they went through all these different sorts of permutations to finally get to the Cars.

“So it was about 10 years of the tip of the iceberg, but they go through all this different stuff, casting off members, casting off styles, Ric finding his voice. And then, as the band gets successful almost immediately in that first year, things start to change pretty quickly. I’s not really until after their third [1980’s Panorama] or fourth record [1981’s Shake It Up] where everybody starts to go into their different corners a little bit. And specifically, the relationship with Ben and Ric, which was at the heart of the band, starts to deteriorate primarily from neglect and almost antagonism by the end.”

The book gets to the heart of that band dynamic, with Ocasek calling the shots as the main songwriter; not only were there tensions between him and Orr but also in his relationships with Easton and Robinson. Janovitz also paints a very nuanced portrait of Ocasek, who was an enigma of sorts when it came to his personal life, even to his bandmates.

“I’m not sure if I’ve ever heard of anybody who had this sort of compartmentalization that was so secretive,” Janovitz says. “Here’s an example that’s sort of the most glaring one in the book: They’re well into the [the tour for] their second album [1979’s Candy-O]. And it’s only then that Greg learns that Ric had a family he had left behind in Ohio before he went to Boston. He had never explained it to the band. They never discussed this kind of stuff.

“As a guy in a band [Buffalo Tom], I can see guys not talking to each other about stuff if you’re just putting together a band as a professional thing. Everybody plays a different role in different aspects of their lives to some extent, right? Very few people are consistent all the way through their lives…But nobody was more drastic at that than Ric.”

The book also does a deep dive into the making of the Cars’ seven albums, including the experimental Panorama from 1980, which was at the time misunderstood because it eschewed the mainstream sound of the first two records. “It actually sounds timeless in its own way,” says Janovitz. “It’s like really good electronica that I don’t even think fell out of favor ever. Whereas maybe Heartbeat City seemed instantly dated to me, even listening to them as a 17-year-old wannabe hipster. But even those sounds have sort of had their comeback, like the 1975 bringing back those washy, synthy sounds.

The band returned to their accessible form on 1981’s Shake It Up with the hit title song, and then went for the brass ring in the MTV era with the aforementioned Heartbeat City in 1984. It was produced by Robert John “Mutt” Lang, known for painstaking perfectionism in the recording studio, as heard on Def Leppard’s Pyromania. “He’s applying those same principles and sounds and pasting them onto the Cars,” Janovitz says of Lange. “But the Cars, at least in the form of Ric, were, at least early on, a willing accomplice. He was going for pop hits, not just rock and roll hits. He’s going for Michael Jackson’s Thriller and the sounds that were on the air like Thompson Twins or Spandau Ballet, whatever it is. So these are the sounds, and you want to sound now. And that’s what they wanted.”

Perhaps the most heartbreaking part of the book is Orr’s personal issues after the band’s breakup following 1987’s Door to Door album; he died from pancreatic cancer in 2000 at age 53. “I’ve been using the word ‘dark’ [on] how dark it got for him,” Janovitz says. “I think he got dinged so much by being in the band. Who knows if he would have had substance issues, anger issues or rage issues that would have bubbled up somehow? I should say there were no indications of that through the history of his life. But it had to be at least the breakup of the band and his treatment by Ric had to be some factor therein.”

“I don’t think many people knew this until the book came out: Ben’s ex-wife, Jude, was telling me about these times in the ’90s when Ric would call, and Ben just wouldn’t take the call. So Ric was reaching out with an olive branch, but I think he felt the damage had been done and he was trying to, at least, explain.”

About a decade after Orr’s passing, the other surviving members of the Cars reunited for 2011’s Move Like This album. “I think Ric wanted to make another record,” Janovitz says. “He had tried all these different solo things. They weren’t happening…It’s like getting together with old friends where you just pick up where you left off. There’s a certain chemistry that you just plug into. I think people see stuff as cash grabs when they’re not always cash grabs. Sometimes it’s just like getting that magical feeling back again, where it’s not an uphill battle. It all clicks together because you guys know each other at this molecular level, almost.”

What emerges from the Cars’ story through Janovitz’s book is a tale of perseverance, perfect timing, indelible songwriting and musical chemistry, creative and personal tensions, and an influential legacy. On what he hopes people will learn from reading Let the Stories Be Told, Janovitz reiterates that “this is a band, and this is what happens in a band. And these are the band contributions. These are five important cogs in a machine.”