A recap from last time: Anytime the Federal Reserve makes a decision about the rate of the federal funds rate, it’s important.

Many interest rates key off the federal funds rate, or FFR. It directly — or through other things it influences — helps set a massive number of important interest rates. Governments, corporations, institutions, investors … even consumers, because credit cards, auto loans, other forms of financing all move with the FFR.

There are nine meetings during the year. The last one is in December — the 9th and 10th. For months, many people assumed that there would be a rate cut. CME Group, a major derivatives marketplace with expertise in risk, has a tool called FedWatch. It monitors the 30-Day Fed Funds future, a marketplace used to offset short-term interest rate risk, to see what the broad set of investors thinks will happen.

There’s a growing belief that the Fed will want to stay put. There are two complications they face: congressionally imposed dual mandates and a lack of important federal data sources.

Duel Of The Dual Mandates

Discussion of the Fed’s dual mandates is actually a bit off. One could argue there are three, as the Federal Reserve quotes from the original congressional legislation about monetary policy: “so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

Maximum employment is a relative term. As the Brookings Institution explains, “maximum employment – sometimes called full employment – is the highest level of employment the economy can sustain without generating unwelcome inflation.” Stable prices are also relative to inflation, which the central bank targets at a rate of roughly 2% a year. The moderate interest rates are also tied to inflation.

Essentially, the central bank’s responsibilities, according to Congress, condense to the management of inflation to a degree that makes everything work. Unfortunately, when things go wrong, the Fed traditionally undertakes different solutions. Higher unemployment? Reduce the FFR to stimulate business activity. Rising prices? Increase the FFR to slow demand and, in theory, eventually reduce prices.

However, the process of looking at the world from outside the cadre of economists and incorporating some memory raises questions. Often there is an apparent correlation between economic activity and interest rates, but far from always.

The Fed Knows It’s Not Always Right

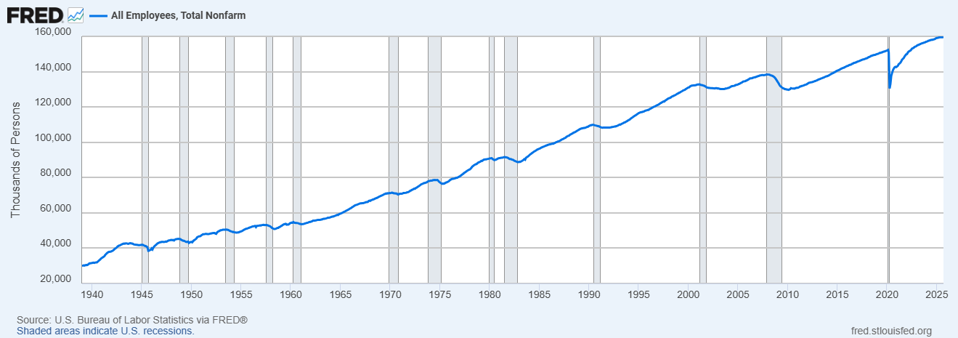

Since the end of the Great Recession, the Fed had tried a drastic drop in the FFR to stimulate the economy. That worked as well as playing out a rope in hopes that the slack would push a sailboat from the dock. There has to be energy to move the machine. Eventually, many people were hired, it’s true, but that happens after disastrous economic crashes — after every recession — and is a function of customers and markets. The graph below shows the movement of people employed during and after recessions (represented by vertical gray bars).

An equivalent example was the Fed’s interest rate cut during the Covid pandemic. What drove inflation was the global shutdown of supply chains and the unavailability of common products, not an excess of demand. The result was that immense waves of liquidity flowed into assets like stocks and real estate because normal fixed-income investments, like Treasury and corporate bonds, provided virtually no income.

The economy is complex and moving one interest rate is simplistic. The Fed has to lean one way or the other to support whatever seems to face the greatest threat. When there is question about the labor market and inflation, the decision is painfully hard.

That is why information is so important.

Missing Critical Data

Unfortunately, the government shutdown upset one of the primary sources of information. The September jobs report finally came out and, at least on the surface, it was encouraging. But October’s is cancelled, as are the October Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, and real earnings report. Also gone is the Job Openings and Labor Turnover report for September.

The Fed depends on extended flows of information to make decisions. Their choices don’t flip on a month’s shift. The markets can practically get whiplash as a res

As of November 19, there was a 30% chance that rates would come down a quarter of a percentage point, according to FedWatch, and a 70% chance they would remain the same. A week before, the odds were roughly flipped: about 63% chance of a rate cut and 37% chance of none. Then, on November 21, after the release of the September jobs report, the numbers flipped again. A quarter-point cut is now seen as having a 71.5% chance of coming true, and a 28.5% probability of no cut.

No one knows what will happen.