Organizations love to announce mentorship programs. Cohorts, matching systems, Individual Development Plans that promise renewed energy and broader possibilities. The language feels bold. The intention feels modern.

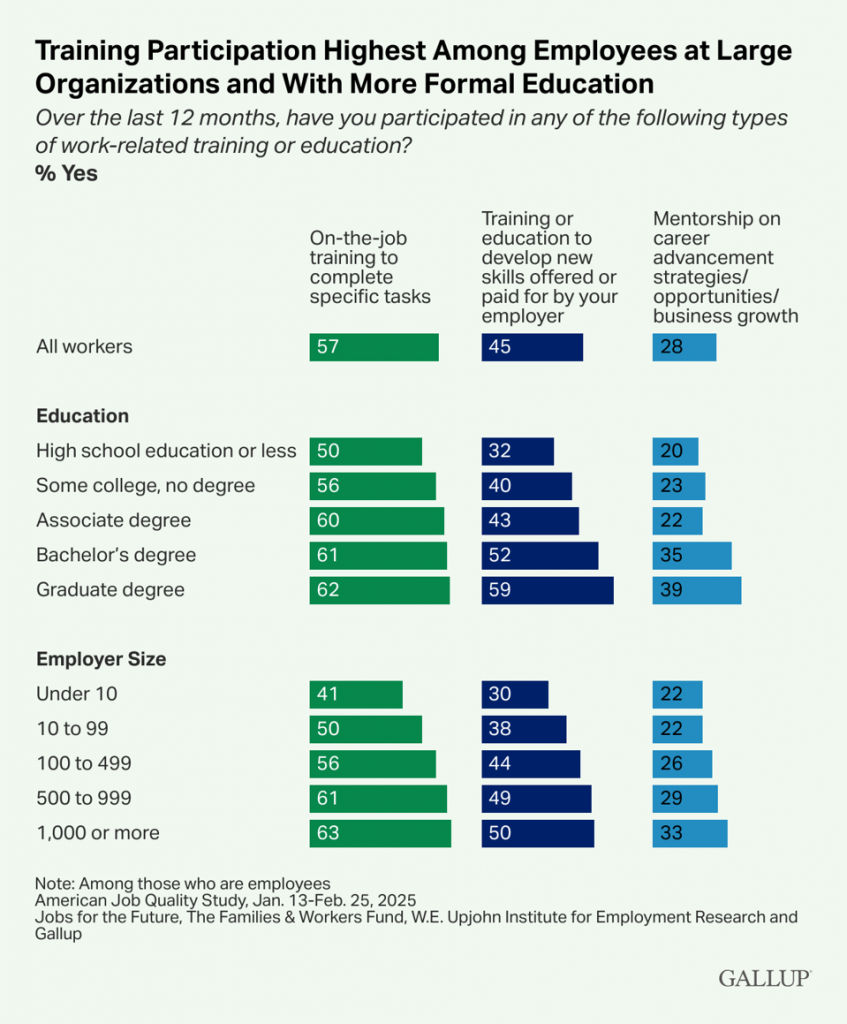

Yet Gallup’s American Job Quality Study shows only 28 percent of workers received any mentorship tied to career advancement this year. Even in the largest organizations the number barely reaches 33 percent. The promise keeps expanding. The experience stays narrow.

I learned this early in my own career. I was assigned a mentor who was considered one of the best in the business. I remember the first call clearly. Sharp insight. Warm curiosity. A sense of real possibility. The next few calls were strong too. Then the cancellations began. Small things at first. A shifted time. A quick reschedule. Another meeting squeezed into the same slot. Then the disappearing act that happens so often in corporate life when the calendar becomes a wall. The meetings stopped showing up entirely.

Somewhere in HR’s pairing dashboard that relationship probably counted as a success. But the actual experience had dissolved. The momentum faded. The curiosity faded with it. Time was lost, and so was the potential that could have come from an early relationship that mattered.

Oddly enough, the best mentoring I ever received happened outside any formal program. It came when I traveled with a top consultant. There was no agenda. No structured assignment. No official pairing. Just proximity to someone exceptional. Watching them operate taught me more than any scheduled conversation ever could. The observations mattered. What they did well mattered. What they avoided mattered just as much. You learn quickly from excellence, but you learn even faster from its edges. Many executives I coach describe their formative mentoring moments the same way. Someone let them observe. Someone gave them access. Someone showed them the small decisions behind the big decisions. That is mentoring as an observational discipline.

And that is the part the corporate systems keep missing.

Mentorship has become systemized, and that is where it breaks

Most mentoring programs are built like learning modules. They feel organized. They look scalable. They signal that the company is “doing something” about development. But human growth does not follow instructional design. Mentorship is not a curriculum. It is a relationship with purpose, and that is exactly what the systemized versions struggle to hold.

Most mentoring fizzles because no one is clear about what the mentee is actually trying to grow toward. Without shared purpose, conversations collapse into polite updates, generic advice, or a rehash of recent frustrations. Programs report participation numbers while people quietly disengage.

And there is a second issue. Mentoring has started to carry an elitist signal. Being assigned a mentor often implies that someone has arrived, that they are being invested in, that they have been selected for something bigger. That is flattering, but it narrows access. It concentrates development at the top instead of distributing it where it can do the most good.

Organizations often identify high potentials first and mentor them later. That sequence is backward. Mentoring is one of the ways potential is discovered. People stretch faster when someone invests in them early, before their roles and expectations harden. The earliest years of a career are full of questions but light on guidance. Those years are exactly where mentoring should begin.

Strengths alignment matters more than seniority

Most matching systems pair people according to level or function. That is why so many mentoring conversations feel like formal check-ins rather than real development. Strengths alignment is a better way to match. When a mentor understands how someone naturally thinks and operates, the guidance becomes grounded rather than abstract.

It also makes the discussions more honest. A strengths-aligned mentor is not trying to mold the person into a miniature version of themselves. They are helping them stretch inside their best pattern. The difference shows up in the questions, the feedback, and the risks the mentee feels confident taking. Chemistry cannot be forced, but strengths alignment raises the probability that both sides find value.

Mentoring-in-name-only wastes time and opportunity

Many employees list mentoring on their IDPs. It looks responsible. It creates the appearance of movement. But behind the scenes there is no follow-through. No shared direction. No defined outcome. Mentors improvise. Mentees wait. Eventually the relationship fades into a vague memory of one or two conversations that never built momentum.

A simple fix helps more than most organizations expect: a mentorship contract. Not a form for HR. A shared understanding between mentor and mentee about why they are meeting and what success looks like. The strengths the mentee wants to deepen. The experiences they want to attempt. The decisions they want exposure to. The pacing of the meetings. The boundaries of the relationship. The kind of support they prefer.

Without that clarity mentoring becomes a calendar entry. With it the relationship becomes a learning engine.

Stop treating the 70-20-10 rule as wisdom without design

The 70-20-10 idea has lived in leadership development for decades. It is repeated so often that people stop examining whether they are actually designing the twenty or the seventy. Most organizations treat it as a slogan rather than a developmental framework.

What we know from years of Gallup research is that leadership growth accelerates through key experiences. Stretch assignments. New markets. Cross-functional work. Failure followed by recovery. Exposure to real-time decision making. Mentoring is powerful when it connects someone to experiences like these. That is the twenty percent that actually moves careers forward.

Mentoring becomes weaker when it limits itself to general advice or surface-level discussions of weekly challenges. Careers grow through challenges that expand capacity. Mentoring must create access to those challenges, not circle around them in conversation.

The best mentoring is not another program. It is access to how strong work actually happens

Emerging leaders often describe their most meaningful development moments the same way. They were invited into rooms they technically had no credentials for. They watched how senior leaders prepared, hesitated, argued, adjusted, and judged. They saw the craft behind the work and the discipline behind the confidence. Many say their strongest mentoring didn’t come from formal programs or assigned pairings, but from being trusted to observe real decisions as they formed. That exposure shaped them more than any structured session ever did.

This kind of mentoring cannot be systemized. It depends on leaders who open the door, even briefly.

Mentoring should build identity, not just performance

The best mentors do more than develop skill. They help someone understand who they are at their strongest. They help shape a sense of direction. They influence how someone thinks about future roles. They contribute to identity, not just output.

That is the part of mentoring that cannot be replicated through structured programs. It lives in the relationship.

Mentoring works when it starts early. When it aligns with strengths. When it connects to real experiences. When it follows a clear contract. When it avoids the elitist logic of “earning” a mentor. When it builds the person rather than the program.

Everything else is activity.

If organizations want mentorship to matter again they must stop treating it as a system and start treating it as one of the most effective ways to grow a person’s future.