You will probably remember that in your Economics 101 class you were taught that the origins of money lie in barter (which is not true, but not relevant to my point here). You had some eggs, you wanted some milk, so you had to find someone with milk who wanted some eggs, and then you had to work out how many eggs for a quart of milk. So for a transaction to take place, you had to find what economists call “the double coincidence of wants. That is a lot easier in a networked economy.

Barter Breaks Down

As society scales, it becomes increasingly difficult to find a double coincidence of wants that can complete a transaction in reasonable time. In a big city, finding someone who needs your skills as a Dungeons & Dragons Dungeonmaster while having a crate of spare Leffe Blonde beer can be very time consuming. Hence, the story goes, society developed cash that could be exchanged asynchronously for these valued services and goods.

But what if finding someone who needs help in finding and configuring a web site while simultaneously baking excellent cakes and at the same time finding a web host setup specialist who needs cakes for a company outing was not time consuming and doomed? What if the existence of a global network connecting all such people meant that you could find this double coincidence of wants in a few minutes? Well, could then you could go back to barter and forget about the intermediary of dollar bills or Dogecoins?

While barter has been around forever, it has mainly been informal. Many companies and organizations do use it as a regular part of their business dealings. The International Reciprocal Trade Association noted that participating businesses were already transacting approximately $12-14 billion globally back in 2021, with that number expected to grow year after year.

Well, it is certainly growing quite quickly in certain parts of the world now. In one transaction identified by Reuters from two trade sources, Chinese cars were traded for Russian wheat. According to one of the sources, the Chinese partners in the deal asked their Russian counterparts to pay in grain. The Chinese partners bought the cars in China for yuan. The Russian partner bought grain with roubles. Then the wheat was exchanged for cars.

It is easy to imagine how the matching of wants with wants might be turbocharged online. Digital barter networks are emerging as a transformative force in peer-to-peer finance, enabling individuals and businesses to exchange goods and services without needed the traditional intermediary of money. New technology means a reputation economy built on transparent, secureA and efficient barter transactions at scale. I understand why the proponents think that digital barter networks could empower local communities to optimize resource utilization and collaboration. This may well look more appealing to communities amid economic uncertainty meaning that barter becomes a viable complement to modern monetary systems.

But now imagine what a tokenised version of those networks might look like. In a reputation economy where someone who buys a token for a bushel of wheat can be sure (through institutional guarantee) that the bushel of wheat exists, or will exist, then bots can easily assemble complex trading strategies to ensure that a factory gets all of the inputs it need via a series of global, instant transactions moving resources around.

Now if that sounds a little far-fetched, imagine how it must have sounded back in the 1990s — before the web, never mind before the blockchain — when the man behind “lateral thinking”, Edward de Bono set out his thought experiment in which IBM might issue “IBM Dollars” (what we would now called “tokens”) that would be redeemable for IBM products and services, but are also tradable for other companies’ monies or for other assets in a liquid market.

When I first read de Bono’s ideas of tens of millions of tokens in circulation, constantly being traded on futures, options and foreign exchange markets, I thought that perhaps such “money” might not suit the mass market because transactions involving swapping around many different kinds of token to complete a transaction would be too complicated for people to deal with. But that’s not the world that we will be living in. This is not about transactions between people but transactions between my virtual me and your virtual me, the virtual Waitrose and the virtual HMRC. In other words, transactions between my agent and your agent, transactions between agents capable of negotiating between themselves to work out the deal.

Dr. de Bono foresaw this in his pamphlet, writing that pre-agreed algorithms would determine which financial assets were sold by the purchaser of the good or service depending on the value of the transaction… the same system could match demands and supplies of financial assets, determine prices and make settlements. He also wrote that the key to any such a system would be “the ability of computers to communicate in real time to permit instantaneous verification of the creditworthiness of counterparties”

Digital Barter Makes Sense

Well-known fintech investor Matt Harris, a partner at Bain Capital Ventures, predicted the same thing. He wrote that rather than money as we know it, in the future “our assets will be 100% invested at all times”. In this vision of the future of money, transactions will be settled through the transfer of baskets of assets without market participants needing to liquidate any assets into cash, or stablecoins or tokenised deposits. How will they trade this digital assets? By using the networks being put in place (by Stripe, Google, PayPal and others) for stablecoins.

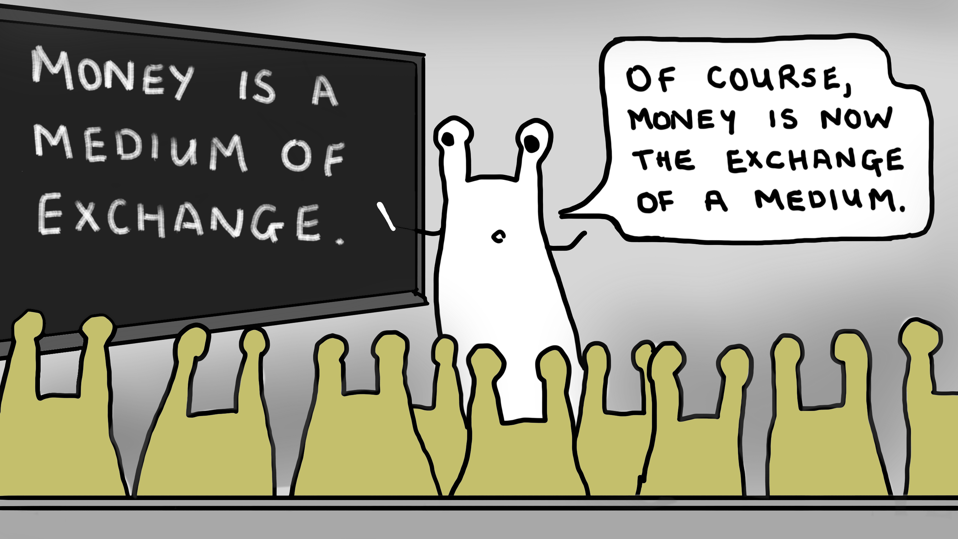

The need for money as transaction intermediary at all, let alone in the form of stablecoins will simply vanish.

What’s more, as I was happy to point out at the time, Matt observed that “Once identity is solved, credit risk becomes easier. You can’t commit fraud or default on your debt just by wriggling free into the ether; your credit history is immutable and follows you everywhere”.

Or, to put it more simplistically, once you know who everyone is, payments are easy, fast and cheap.

All I will add to this clear view of the future is that the rails being laid down for stablecoins now will start as much of a revolution as the rails laid down in England where, 200 years ago to this month, the first ever paying passengers took a 25 mile railway journey at a maximum speed of 15mph, travelling from Shilton to Stockton via Darlington. Whether digital barter replaces money remains to be seen, but it has a big role to play in the networked economy.