It’s the sort of story America loves telling about itself. A story promoting the idea of American exceptionalism. American military exceptionalism. A daring midnight raid. A hero. Captives rescued from under the nose of a wicked enemy. Freedom prevailing over evil.

But Americans don’t know this story by and large. It’s been buried. The hero and villains don’t fit the nation’s stereotypical casting of those characters.

Harriet Tubman (1822-1913) and a crew of formerly enslaved freedom fighters are the heroes of the Combahee River Raid. The bad guys–the villains–wealthy white Southern landowners. Enslavers. Men.

A Black woman getting over on a bunch of white men.

Popular American history didn’t like that role reversal and spit the story out. Now through October 5, 2025, the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC–about 30 miles north of where the Combahee River enters the Atlantic Ocean–revisits Tubman’s escapade.

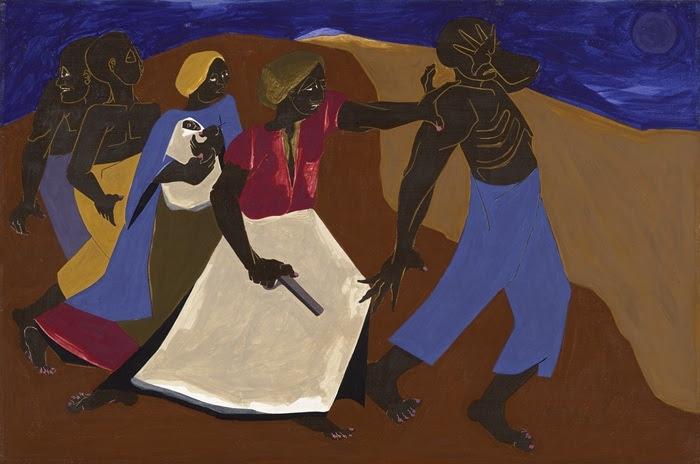

The Combahee River Raid has never been explored this way. The museum exhibition features major works by some of America’s leading artists including Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) and Faith Ringgold (1930-2024), artists who’ve honored Tubman through more than 100 years up to the present day. Paintings and sculptures from collections across the country are combined with striking environmental photographs of the Combahee River shot by Charleston native J Henry Fair (b. 1959). Depicted is a serpentine landscape where the heroic raid took place.

The artworks and photos are displayed alongside historical items, archival images, video reenactments of the Raid, and multimedia testimonials by descendants of the enslaved people who liberated themselves.

The presentation was inspired by Edda Fields-Black’s “COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War.” The book was awarded the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in History. Fields-Black is descended from a participant of the freedom raid. She teamed up with Fair, who provided photographs for her book, to pitch the museum about an exhibition related to the dramatic event.

The Combahee River Raid

In 1863, deep behind Confederate lines, Harriet Tubman led the largest and most successful slave rebellion in United States history. 756 enslaved people were liberated in six hours on that moonlit night in June. The total amounted to more than 10 times the number of enslaved people Tubman rescued during her decade of service as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

The Combahee River Raid was further remarkable because it was carried out by one of the earliest all-Black regiments of the Union army. Her group of spies, scouts, and other freedom fighters piloted three Union steamboats snaking up the lower Combahee River with Colonel James Montgomery of the Second South Carolina Volunteers and one battery of the Third Rhode Island Artillery.

African Americans working in the rice fields on seven rice plantations along the Combahee heard the uninterrupted steam whistles of the US Army gunboats and ran to freedom. Toiling in South Carolina’s rice fields–killing fields–was among the most brutal labor forced upon enslaved people in America.

The morning after the Raid, 150 men who liberated themselves joined the Second South Carolina Volunteers and fought for the freedom of others through the end of the Civil War.

The Combahee River Raid was a monumental moment in American history. A moment mostly eliminated from retellings of the war, and Tubman’s biography.

“A highly successful military raid led by a Black woman defied race and gender norms of the time as well as traditional military authority,” Sara Arnold, Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Gibbes Museum of Art, told Forbes.com. “Additionally, the number of people successfully liberated in the raid powerfully demonstrated the profound yearning for freedom held by those in bondage–a narrative that was suppressed in the aftermath of the war by Southerners in power.”

As is often the case, “Picturing Freedom: Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid” proves the art museum can be the best history museum too.

‘Picturing Freedom’

In 2022, Fields-Black and Fair approached Gibbes Museum President and CEO Angela Mack about the concept of a museum exhibition related to the Tubman book they were working on.

“As an art museum we immediately recognized the importance of placing a visual history around this historic milestone‒to tell this story through art,” Mack said. “This is an epic American story with a national legacy and universal impact.”

The Museum invited Vanessa Thaxton-Ward, Director of Hampton University Museum, to guest curate the show. She hand-picked artworks from across the United States.

“I want this exhibition to show that Tubman was a whole person–she was more than the conductor of the Underground Railroad,” Thaxton-Ward said. “She was a wife, she was a mother, she was a daughter. We also wanted to show how hard life was for enslaved laborers in the rice fields, especially the children. Many of these families were brought to the region because of their prior knowledge of the rice culture in West Africa.”

After the war, many returned to the same rice plantations from which they had escaped, purchased land, and started families. They created the distinctly American Gullah Geechee dialect, culture, and identity, celebrated today as one of Harriet Tubman’s most significant legacies.

The Gullah Geechee culture is marked by its unique language and living styles. Fields-Black’s ancestors are from this area near Charleston and the Combahee River region; she is of Gullah Geechee descent. During the year-and-a-half that Fields-Black lived in the region researching her book, she walked the terrain where the historic river raid took place‒in the middle of the night under the light of the moon–retracing the freedom fighters’ steps.

The show carefully recreates the full journey of these brave soldiers and freedom seekers, including through a video re-enactment. One of the enslaved laborers who was freed during the raid will be portrayed in the video by the South Carolina-based actor, educator and author Ron Daise, known for his advocacy of and expertise in Gullah culture and language.

Stephen Towns

“Picturing Freedom” displays work from luminaries of American art history–William H. Johnson (1901-1970), and Aaron Douglas (1899-1979)–alongside contemporary artists.

One of the more recent pieces is Kevin Pullen’s (b. 1955) Can you break a Harriet (2024). The painting refers to the decade-plus effort to have Tubman honored on the U.S. $20 bill, replacing murderous tyrant and slaver Andrew Jackson.

Stephen Towns (b. 1980) has a pair of Tubman quilted pictures in the exhibition, and a nearly unbelievable connection to the Gibbes. The South Carolina native formerly worked the front desk there part time more than 20 years ago.

“I was just trying to figure out how to get myself in the industry,” Towns told Forbes.com. “Being in South Carolina, there were very few opportunities and the Gibbes was the only art museum in the area.”

Like most Americans, Towns only knew Tubman on the surface. She had a blurb in the World Book encyclopedia set his family owned growing up. He wanted to know more.

“Having read a couple of her biographies, she felt like a superhero to me,” Towns said. “To think that someone has gone through as much as she went through, to have escaped being enslaved, and then to go back several times to get family members and friends, it’s unheard of.”

Learning more about Tubman’s heroism, including the River Raid, inspired Towns to produce a series of Tubman quilts, two of which are in the show. One of those artworks, And I Shall Smith Thee (2018), recalls an episode from Tubman’s life Towns found particularly powerful.

“When she was young, she was hit by this two pound weight that an enslaver had thrown at her, and from that period, she had these narcolepsy spells and dizzy spells where she could fall asleep at any time,” Towns explains. “To realize that she had that throughout her life, these debilitating headaches, and she still did everything that she did through enslavement and also being a part of the women’s movement, it’s insane the accomplishments this woman has done.”

Another aspect of Tubman’s life most people don’t realize. That American history glosses over. Tubman was disabled as a result of the childhood assault. She sustained a brain injury. In 1898, she underwent brain surgery in an attempt to relieve the pain. Without anesthesia.

America doesn’t like its heroes Black, female, or disabled. Tubman was all three. Illiterate on top of it all. Slaveholders, of course, withheld education from the enslaved, along with nearly everything else. Yet Tubman overcame it all.

“She was a young child, and she had gone into this general store, and she was protecting another enslaved person that was being abused,” Towns explained of the inspiration behind And I Shall Smite Thee. “I used that moment as a moment of magical realism. I think for her, it kind of felt like magic, where she was in these fainting spells, and (had) these daydreams and these visions; that was her way of communicating to God to find different ways and routes of doing everything that she’s done in her life. Even though that’s a very painful moment, I use the power of that, and that’s why you see her throwing a stone at the alligator.”

And I shall smite thee.

On Veterans Day, November 11, 2024, more than 100 years after her death, Tubman was posthumously commissioned as a Brigadier General by the Maryland National Guard. She was the first woman in the U.S. to lead an armed military operation during a war, yet she was never given official status by the military, and fought for decades for her military pension.