In Part 1 of this interview series with former NASA Mission Control specialist Steve Bales, we covered his critical “go” decision when 1201 and 1202 alarms sounded as the Apollo 11 Lunar Module was descending to the surface of the moon. We also covered Bales’ ensuing “fame” and the signing of autographs for the rest of his life.

Here, in Part 2, we examine the last 2,000 feet of descent of the Lunar Module and the extensive preparation of the Mission Control team prior to Apollo 11’s launch in 1969. Following are edited excerpts from a longer phone conversation with Bales.

Jim Clash: It is well-documented that, at the last minute, Apollo 11 had to fly over a lunar crater and land on the other side of it, using precious fuel in the process. Take us through that.

Steve Bales: [Flight Director] Gene [Kranz] had said no other abort calls below 2,000 feet, except for low fuel. The Lunar Module didn’t have an accurate fuel gage. Neither did we on the ground. But when the tank got to a certain level – I think a minute and a half left – you would be alerted to start a stopwatch. Suddenly Bob Carlton, the engine controller, is running the entire program with a stopwatch. Some 400,000 people had made and supported the vehicle, with billions and billions of dollars of taxpayer money, and it’s now all up to a guy with a mechanical stopwatch [laughs].

Bob calls “60 seconds,” and CAPCOM relays that to Neil [Armstrong]. Normally, in simulations, at about 600 feet the crew is gradually descending, but in this case they’re zooming horizontally above the surface, and we have no idea why. Turns out they needed to land long because a crater with boulders was just under them. Neil had to pilot manually to fly over the crater. That takes more fuel, of course.

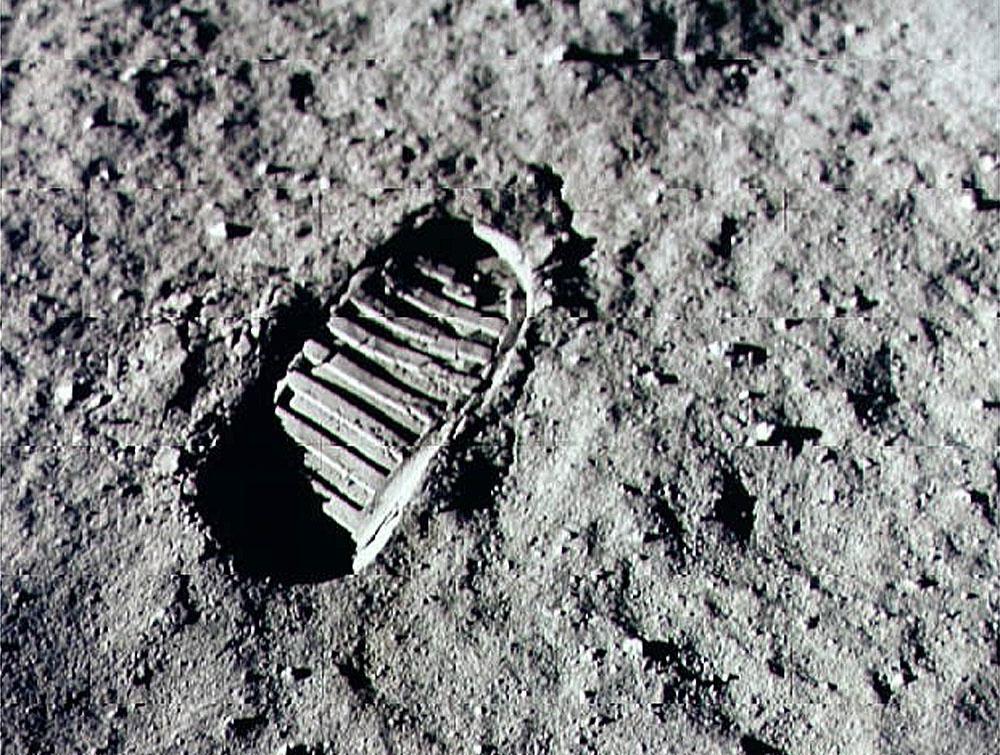

Next you hear, “30 seconds.” I thought, “My God, we aren’t going to make it.” But then you see the contact light, meaning one of the vehicle probes has hit the lunar surface, followed by Buzz [Aldrin] saying, “Engine stop.” Shortly after that, the historic call came down from Neil, “Houston, Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed.”

They only had 17 or 18 seconds of fuel left. That historic stopwatch, by the way, is now in the Smithsonian [National Air And Space Museum] in Washington, DC.

Clash: Was anything special said to the controllers just before the Lunar Module started down?

Bales: The [Mission Control] room was so tense you could cut it with a knife. I’m probably the most tense. I tend to get excited. Some of the older guys were a little cooler. So we were all sitting there, waiting for 15 minutes of blackout as the crew came around from the backside of the moon.

Gene Kranz told the 30 or so of us to go from his radio loop to a special loop. His flight director loop was recorded and went around the world. This other loop, called conference, was private. After we all switched over, he said, “This is what we’ve waited our entire lives for. This is what we’re going to do today. I have confidence in every one of you. I just want you to know this: However it ends, we walk out as a team.”

Yeah, if I messed up, he was going to take responsibility, too, because he had picked us. Then he told us to lock all of the doors, because nobody was coming into or out of Mission Control until Apollo 11 either had landed, aborted or crashed.

Clash: I realize most of the training you did was fairly intense. Any amusing anecdotes amongst all the seriousness?

Bales: The very first simulation we did was for a descent. I sat down and plugged into the console. Somebody came over and plugged in beside me. I looked up and saw it was [Director Of Flight Operations] Cris Kraft. He never did that with anybody. I was shocked. He knew how important this position was, knew the guidance guy would probably be in the hot seat during the actual mission.

It was supposed be a normal simulation without any surprises. But, as we started down, the guidance system began deviating badly. When we got halfway down, I said, “Gene, abort,” and the crew did it. Somehow, the program had been misaligned by a degree. Afterwards, Chris slapped me on the back and said, “Good job, boy!” I never saw him again. I think that was my training day, and I passed [laughs].

Another thing: As a controller, you learn to listen to at least four conversations at once, then pick out the one you really need to hear and ignore the others. I’m glad I lost that capability over time. I’d walk into a meeting or restaurant later in life and I could hear all of these people talking around me, what each was saying, and it started to bug me [laughs].