After lowering the federal funds rate by a full percentage point in the second half of 2024, the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates on hold this year, and most observers do not expect it to begin cutting rates until this fall. The principal reason is that the larger-than-anticipated tariff hikes in early April fueled concerns that it could spawn stagflation, in which prices rise as the economy softens.

In the meantime, President Trump announced a 90-day suspension in reciprocal tariffs and the U.S. and China reached a truce with China. Consequently, the effect of price hikes associated with increased tariffs may be delayed for a while.

While inflation has not increased materially thus far, Fed officials expect price increases will unfold in the second half of this year. For example, the median projection of FOMC members for core PCE inflation was recently raised by three tenths of a percentage point to end this year at 3.1%.

This projection appears reasonable considering that the current effective tariff rate of the U.S. has increased five-fold this year to roughly 16% according to the Yale Budget Lab. At the same time, the U.S. dollar depreciated by more than 10% against a basket of currencies, marking the steepest decline to start a year since 1973.

Normally, import prices would rise significantly in response to such developments, albeit not necessarily by the full amount of the tariff hikes and dollar depreciation.

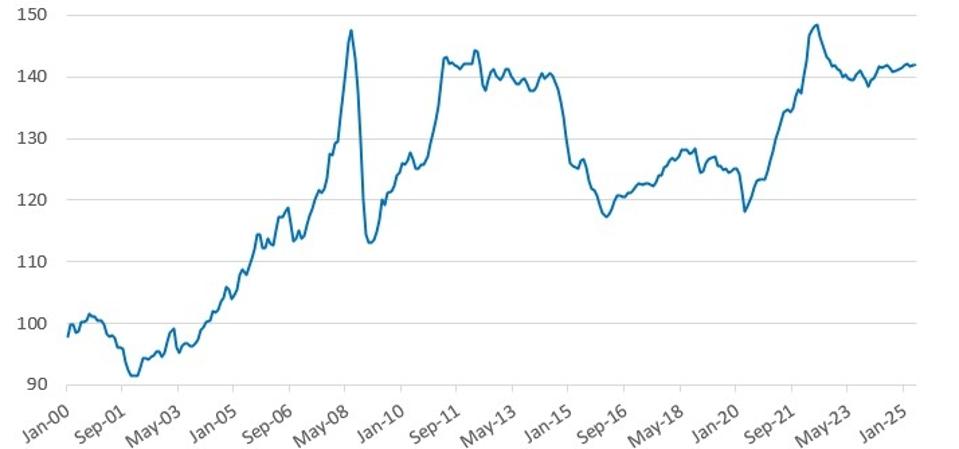

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, supply-chain disruptions contributed to a 25% spike in import prices (see chart). This was the primary way that goods price inflation was transmitted throughout the U.S. economy.

US Import Price Index: All Commodities

In comparison, import prices are little changed this year. In fact, a recent report by the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) found that prices of imported goods have fallen somewhat, and they have dipped faster than overall goods prices since February.

The CEA report breaks down the PCE price index and CPI index into domestic and imported components, and it presents graphs that show the divergence between the two components. The report concludes: “These findings contradict claims that tariffs or tariff-fears lead to an acceleration in inflation.”

One explanation for the conundrum is that exporters and importers wanted to beat Trump’s April 2 announcement, and they rushed to get shipments out before higher tariffs took place. During that period, exporters may have been willing to accept price reductions to get goods shipped in time. Importers may also have been reluctant to pass along higher costs until they had a clearer idea of where tariff rates would settle.

There are also long lags between the onset of tariff and currency changes and the impact on goods prices that need to be considered.

Forward-looking indicators suggest this may be case now. For example, the U.S. purchasing managers surveys for both manufacturing and non-manufacturing show about 70% of businesses are anticipating price increases in the balance of this year. Small businesses also expect to raise prices, albeit by less than for large companies.

Another indication is that capital markets anticipate higher inflation in the near term. Swap rates spiked on April 2 following Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement, but they are off their highs now. One-year swap rates, for example, are up by about 80 basis points this year, while five-year rates are only up by 15 basis points. This is consistent with the view that tariffs will provide a one-time boost to prices.

So, what could cause the Fed to ease monetary policy in these circumstances?

My take is that the global trade war will impact the U.S economy both by boosting prices and by increasing uncertainty. Although the price effects will play out over time, the impact of heightened uncertainty on the economy already is apparent and will be prolonged.

The July 9 deadline for reciprocal tariffs has passed with no new deals being announced and the deadline being pushed ahead until August 1. In most instances, the letters that were sent to countries showed tariff rates that were close to those on April 2. However, those for Brazil, Mexico, Canada and the European Union were markedly higher.

Meanwhile, President Trump announced that tariffs on copper would be increased by 50% as of August 1. He has also threatened that tariffs on pharmaceuticals could be increased by up to 200%. In a letter to clients, Andy Laperriere of Piper Sandler points out that the sectoral tariffs the Trump administration is considering could impact 40% of US goods if fully implemented.

The heightened uncertainty has been felt by American consumers, who slowed spending in the first half of this year, with consumer spending running at less than half the pace in 2024. It also shows up in a significant slowing of hiring by businesses in the first half of this year.

Prior to the June jobs report, there had been talk that the Fed might consider lowering rates at the July FOMC meeting at the end of this month. These expectations faded when the June jobs report showed a higher-than-expected increase in non-farm payrolls of 147,000. However, the headline number masks the fact that half of the job increases were in the government sector and are likely to be temporary.

Weighing these considerations, my take is that Fed will eventually respond to an economic slowdown by easing monetary policy. But the pace will depend on the extent to which inflation picks up.

In any case, the Fed’s response will not be as aggressive as it was during the COVID-19 pandemic when the Fed viewed the spike of inflation in 2021 as being temporary. The reason: The Fed does not want to risk making the same mistake again.