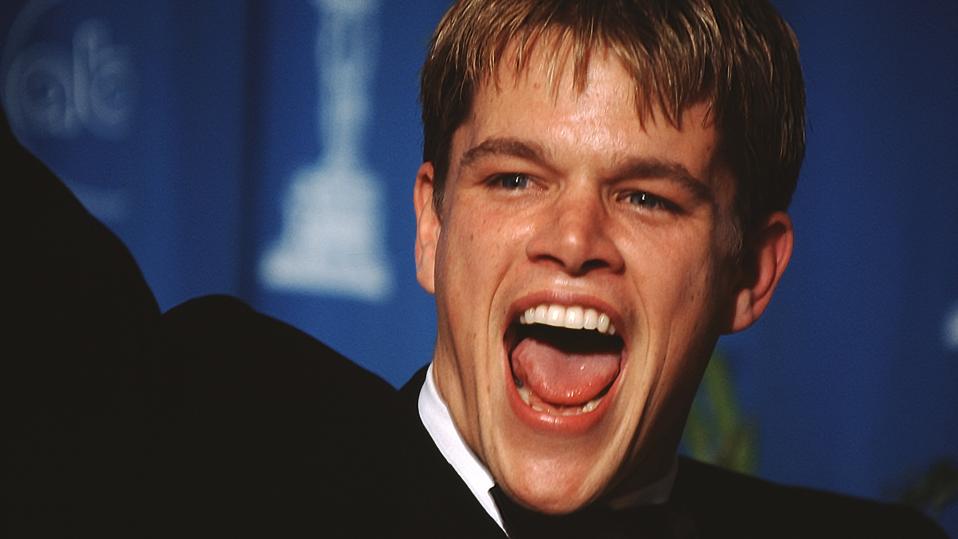

Good Will Hunting won Best Original Screenplay at the 70th Academy Awards, and it’s not hard to see why. The premise of a mathematically gifted, but guarded, janitor working at MIT may lean into a familiar prodigy fantasy, but what elevates the film isn’t the math. It’s the emotional architecture: the way it slowly, deliberately strips Will (played by Matt Damon) down to his core.

What begins as a story about genius quickly becomes something else. Once we are immersed in Will’s world — a tough street orphan from South Boston clinging to his friends and his firewalls — the film introduces Skylar. And with her, it reveals its true agenda: to make us confront the limits of our own capacity to love and be loved.

Here are two takeaways from the movie that, I think, are the most important:

1. ‘It’s Not Your Fault’ Isn’t Just About Trauma

On the surface, the iconic scene of Sean, Will’s court-ordered therapist played masterfully by Robin Williams, quietly repeating “It’s not your fault” until Will finally breaks is a release of childhood pain. And it is. But if you’ve been paying attention to Will’s relationship with Skylar, you’ll realize the emotional wound cuts even deeper.

What Sean is really confronting is Will’s self-concept — the internalized belief that he is broken, unlovable and undeserving of care. And that matters. A stable self-concept, research suggests, predicts high-quality relationships.

Without a clear, stable sense of who you are, intimacy starts to feel threatening. If you don’t believe you’re worth loving, you’ll instinctively push people away. This stems from a fear that their love won’t survive your “true” self.

This isn’t just fiction. It shows up everywhere. Justin Bieber, a child of divorce who’s spent much of his life under reality warping public scrutiny since the age of 13, recently posted this on Instagram:

“People told me my whole life ‘Wow, Justin, you deserve that.’ And I personally have always felt unworthy. Like I was a fraud. Like when people told me I deserve something, it made me feel sneaky. Like, damn, if they only knew my thoughts. How judgmental I am, how selfish I really am, they wouldn’t be saying this. If you feel sneaky, welcome to the club. I definitely feel unequipped and unqualified most days.”

What he’s describing is shame tied to identity — the belief that if someone really saw your inner thoughts, they’d take their love back. And that’s exactly what Sean is trying to undo in Will. Not with logic, but with presence. Not with an argument, but with relentless empathy. Because at some point, for all of us, healing becomes about believing that someone could see it all and still stay.

2. Accepting The What-Ifs In Love Is Not Always Easy

When the credits roll and Elliott Smith’s Miss Misery plays, we see Will’s car driving cross-country to California. There’s no voiceover, no final speech. Just motion. And yet, the moment carries the emotional weight of the entire film.

We don’t know what Will’s going to find. And neither does he. But that’s the point. For most of the film, Will is obsessed with control. He hides behind sarcasm, intellectual superiority and street loyalty — not because he doesn’t feel, but because feeling is dangerous. If you admit you want something, you can lose it. If you care too much, you can get hurt. So Will builds a life that’s safe, but small. Until it isn’t.

By the end, he doesn’t have a job lined up. He hasn’t called Skylar. He doesn’t know if she’ll even want to see him. But for the first time, he doesn’t need to know. Because he’s finally made peace with uncertainty, and with the fact that love doesn’t come with guarantees — and that the risk of not knowing is still worth taking.

Psychologically, Will’s earlier avoidance reflects what researchers call intolerance of uncertainty — the tendency to hold back until the outcome feels predictable. It’s a defense mechanism dressed up as logic, but underneath it lives fear of rejection, of failure and of being seen too clearly and left anyway.

And it’s one of the biggest killers of intimacy, growth and joy. People stuck in this mindset often stay in dead-end relationships, cling to familiar pain or reject love before it can reject them. Will’s final drive, then, is a symbolic declaration of emotional maturity. He chooses movement over paralysis. Hope over hurt. Growth over safety.

And that’s what makes the ending so liberating — not because he had to “go see about a girl,” but because he was finally willing to not know what would happen next.

Love can feel intoxicating. Do you have a tendency to become addicted to love? Find out by taking this test: Love Addiction Inventory