To an artist, “influence” can be a dirty word. Influence suggests imitation, derivation.

Admitting influence questions every artist’s highest aspiration: originality.

Of course Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) knew the work of Claude Monet (1840–1926). She studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with an instructor who painted during the 1910s and 20s in Giverny, France, in the same circles as the great master. The Art Institute of Chicago itself has arguably the finest collection of his paintings of any U.S. museum which she surely knew intimately.

Upon moving to France for good in 1968, to the rural village of Vétheuil, her home address was “12, avenue Claude Monet.” Her house overlooked Monet’s house from when he lived there between 1878 and 1881. Monet’s first wife was buried adjacent to her garden.

She read the books, she knew the paintings, so of course Mitchell was influenced by Monet. It was a connection she embraced until recognizing the connection–constantly referenced by critics and in reviews–was beginning to define her.

Then she backlashed against it.

“I don’t copy Monet,” Mitchell said in 1982.

Knowing something about her, it’s not hard imagining Mitchell seething through another interview about Joan Mitchell where Claude Monet ended up being the focus. Her work placed secondary to his.

Because Joan Mitchell was a bad ass.

She was tough. She was an athlete, a good one–competitive figure skater–as a kid. She had a chip on her shoulder from birth despite her privileged upbringing in the Windy City.

Mitchell’s dad wanted a boy; he accidentally wrote “John” on her birth certificate. A physician and painter himself, Mitchell’s father constantly belittled his daughter’s efforts at whatever she applied them to.

As Mitchell increasingly found herself conjoined to Monet, riding in the sidecar, her attempts to gain distance from him turned ridiculous, referring to Monet’s one time proximity to her Vétheuil property as an “unfortunate coincidence.”

Then ugly.

“He [Monet] was not a good colorist,” she was quoted as having said in 1986. “The whole linkage is so horrible…. He isn’t my favorite painter. There’s a much heavier conscious influence from Cézanne. I never much liked Monet.”

From childhood, Joan Mitchell was told she was no good. She fought. She competed. She cleared space for herself in the male dominated world of painting–particularly the mid to late 20th century world of abstract painting. She’d be damned if her career was going to be viewed as subservient to anyone’s, no matter how great.

Antithetical to this, Mitchell was one of the most celebrated artists of her time–male or female, on either side of the Atlantic–enjoying major solo museum shows and praise for her work the likes of which are rare for female artists even today. But remember the athlete. The competitor.

During his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame, Michael Jordan, universally acknowledged as the greatest player of all time, saved room to trash talk a long list of adversaries throughout his career from the high school coach who cut him to members of the media little remembered at the time and utterly forgotten today. Unthinkably petty, but the competitor never stops competing.

Mitchell and Jordan, fellow Chicagoans, would have probably gotten on famously, provided neither stepped on the other’s turf.

Visitors to “Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape,” which opened March 24 at the Saint Louis Museum of Art and remains on view there through June 25, 2023, should know this about her.

“Monet/Mitchell” / “Mitchell/Monet”

“Monet/Mitchell”–you can’t help thinking Mitchell would have pushed for “Mitchell/Monet”–represents the first exhibition in America to examine the relationship between the two master landscape painters with so much in common. Their painterly, physical and energetic canvases reflect a mutual affinity with the landscape, rivers and rolling fields of the greater Paris region.

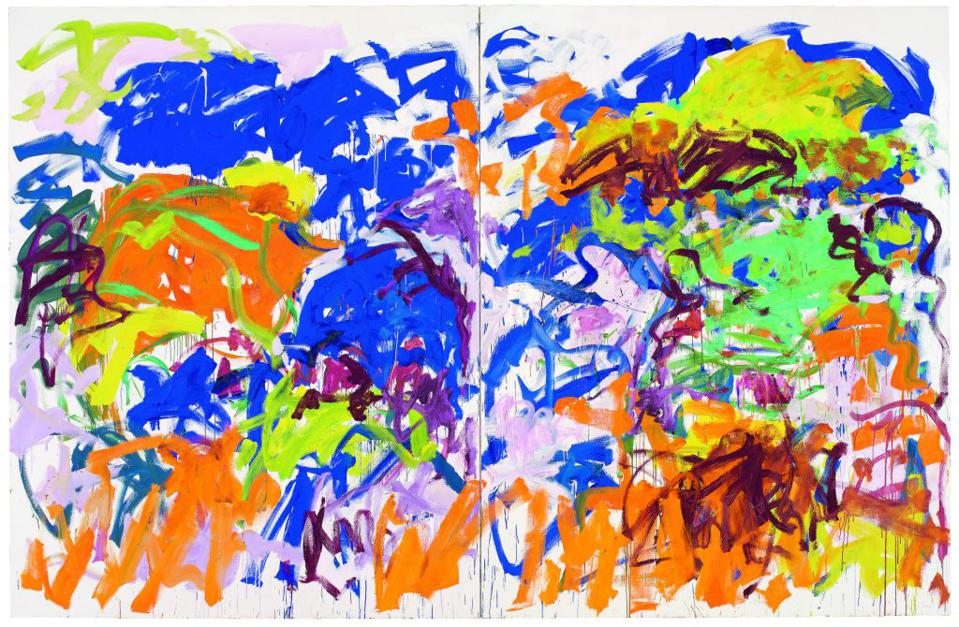

Monumental in scale and overwhelming in impact, the works in the exhibition highlight their shared fascination for expansive, panoramic formats, and their equal mastery of light, color and expressive brushwork. Through 24 paintings, 12 by each artist, the presentation closely follows the development of Mitchell’s work from when she moved to Vétheuil in 1968 until her death there in 1992.

Just don’t call it “influence.”

“I prefer not to use the term ‘influence,’ but rather speak about the fascinating parallels between the two artists,” exhibition curator Simon Kelly, the Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Saint Louis Art Museum, told Forbes.com. “Both saw themselves as landscape painters and were deeply attached to nature. Both painted earth, water, flowers, their gardens. Both used similar, very gestural brushstrokes and palettes of comparably vibrant color.”

Exhibition highlights include striking examples from Monet’s iconic “Water Lilies” series, considered a masterpiece of the Impressionist movement. Of these works, on view from SLAM’s permanent collection will be the central panel of Monet’s Agapanthus triptych, which the artist considered to be among “my four best series.”

Also prominent from SLAM’s permanent collection, Mitchell’s Ici, which translates to “here” in English, a large-scale diptych and one of her last paintings. It was made at a time when Mitchell was sick and yet it has a wonderful energy and vibrancy.

Presented together, the two artists’ works augment each other in unexpected ways.

“Part of the interest of the show is that, for me, Monet emerges as a more abstract painter than we traditionally think and Mitchell as an artist closer to nature than her Abstract Expressionist background might suggest,” Kelly said.

Mitchell, born and raised in Chicago, cutting her teeth in midcentury New York, considered herself a landscape painter despite her urban roots and association with Ab Ex, a movement defined externally by city life, and artistically through the expression of interior emotions.

But there Mitchell was with her big, bold paintings of the outdoors.

“I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me,” she said.

Monet, likewise, worked against type. By the end of his career–into his 80s, eyesight failing, painting to the last–his work became increasingly abstract. Loose. Brushy. Even by the loose and brushy standards of French Impressionism.

The exhibition features two paintings from his masterful “Japanese Bridge” series, circa 1918-24, on loan from the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. They are undeniably abstracted.

“There is an increasing abstraction in Monet’s work in the last decade of his life. He used abstract, non-naturalistic color, flattened space and employed very gestural brushwork,” Kelly explains. “Critics in the 1950s like Clement Greenberg saw Monet’s late work as abstract and him as an important antecedent of the Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s (of which Mitchell was associated). Artists themselves, like Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Ellsworth Kelly, Sam Francis, Jean Paul Riopelle (Mitchell’s longtime partner), and Mitchell herself also played a part in the revival of interest in late Monet in this decade.”

Ironic.

Mitchell and Monet

Most visitors to “Monet/Mitchell” will have some idea of what a Claude Monet painting looks like prior to their arrival. To this day, he remains arguably the most popular and famous painter in history. The Water Lilies, the haystacks, the bridges, the cathedrals, the poppies.

Mitchell, despite her art world fame, hasn’t crossed over into the broader transatlantic culture the way he has, although her name recognition is greater in France than it is in the US.

“Her distinctiveness comes from the way she fused American Abstract Expressionism with the French landscape tradition,” Kelly said. “Mitchell was unusual among the abstract expressionists in the degree of her intense attachment to nature. She’s a wonderful colorist who used incredibly vibrant and gestural brushwork. Mitchell is a major woman artist of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Part of her legacy is that people now recognize the central importance of women artists to this movement.”

As for Monet, nearing the 100th anniversary of this death, what makes his artistic vision endlessly enduring?

“Monet had a rare ability to bring nature to life in iconic themes like the water lilies,” Kelly said. “He’s a wonderful colorist. I think there’s a calming, meditative aspect to his work with which people are able to empathize.”

“Monet/Mitchell” doesn’t present these equally brilliant artists in opposition to each other, it isn’t “Monet vs. Mitchell,” this pairing allows both to be elevated–great athletes playing alongside each other, attaining new heights in the process. Mitchell does not derive from Monet, she extends and expands upon a foundation he built, creating her own foundation from which others have subsequently extended and expanded, artists no more derivative of her than she was of him.