Two decades ago, I saw a play on Broadway called Q.E.D. about the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. It was mostly a one-man show, brilliantly acted by Alan Alda, who played the quirky scientist to a tee.

I had known about Feynman since the 1990s when a book, “Tuva Or Bust,” had caught my attention. In it, Feynman and his friend, Ralph Leighton, chronicled their quest to visit a mysterious place in Siberia called Tuva, at the very center of Asia, full of throat singers, shamans, yurts and triangle-shaped stamps. It was the last one, the stamps, that fascinated the two men most – oh, and the fact that Tuva’s capital, Kyzyl, has no vowels.

Feynman died before he could make it to Tuva (the Soviets were suspicious of his motives as he had worked on the Manhattan Project), but Leighton did make it, and left a plaque at the Center Of Asia Monument commemorating Feynman. I made it my own quest to visit Tuva, as well, to live out Feynman’s dream, and did so for a Forbes story 15 years ago.

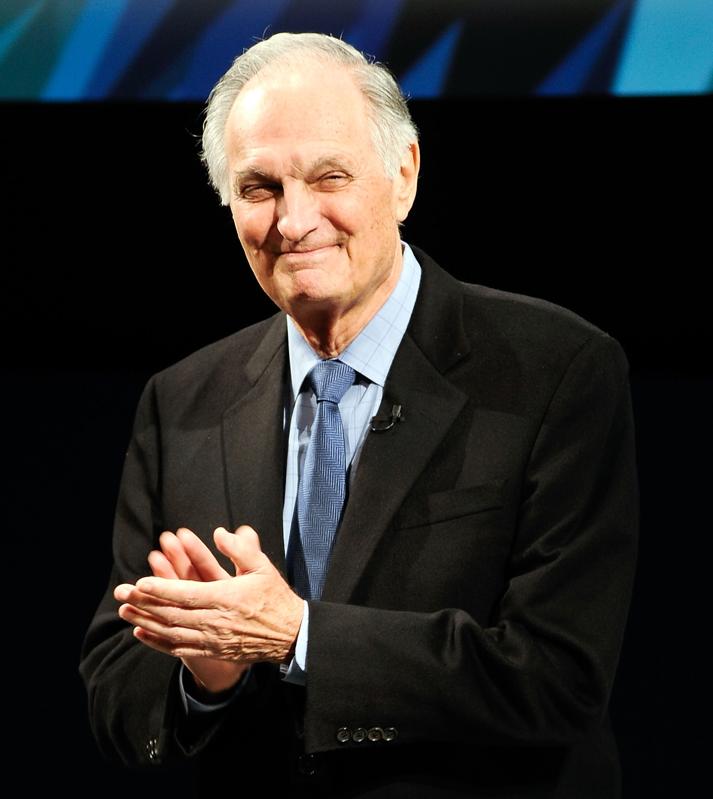

But back to Alan Alda, who is also a complex, fascinating guy. Most folks know him as the meatball surgeon Hawkeye Pierce on the hit TV series, “M*A*S*H.” But Alda is much deeper than just acting, however good he is at it, with a passion for science and for communicating it to lay people.

His Alan Alda Center For Communicating Science at Stony Brook University teaches scientists to better explain complex concepts to average Joes like you and me, and to other scientists. Alda also hosts a popular podcast, “Clear And Vivid,” on which he has as guests scientists and other interesting people from all walks of life.

We thought it would be interesting to catch up with Alda, 88, to discuss all things science, acting, communicating and Feynman. Following are edited excerpts from a one-hour Zoom conversation. This is Part 1 of a multi-part series.

Jim Clash: Take me back to when you first became interested in Richard Feynman.

Alan Alda: When his book, “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman,” came out I believe is when I first got interested. After that book, I read the others, including “Tuva Or Bust,” plus Feynman’s three big lecture books. In the lectures, though, despite that he tried to make them accessible to regular people, you almost needed a graduate degree to follow them.

I was drawn to Feynman, regardless of how smart he was, because he was frank, and never kidded himself. He always said, “You’re the easiest one to fool – yourself.” That’s a great warning, right? Especially when you’re dealing with important questions – not to let your prior opinions rule the day. I had been interested in science for a long time, but that’s how I got interested in Feynman.

Clash: Your Q.E.D. play on Feynman’s life, which ran on Broadway in the early 2000s, took what, six years from concept to stage?

Alda: Gordon Davidson, in California, was interested in doing that play with me, and recommended Peter Parnell, an excellent playwright, to write the script. As hard as we went about it, after a year we still felt we hadn’t captured Feynman. He’s hard, and not just because he’s one smart guy. If you look under the hood, he had many facets; he was several people. At one point, we thought it might be better not to do a play about Feynman, but one about three guys in a hotel room trying to figure out how to do a play about Feynman. It would go on endlessly, never end [laughs].

Clash: Feynman worked on the Manhattan Project. What were his feelings after the atomic bomb was used on Japan?

Alda: What impressed me about Feynman was that he was honest enough to say that while they were working on the bomb, he didn’t think about the consequences in terms of loss of life. What he and the other scientists were excited about was the possibility of being able to solve a difficult problem.

It was only after the bomb had killed so many people in such a dramatic and disastrous way, that he realized the magnitude of what had taken part in. He got very depressed, and it affected his work at Cornell.

But one day in the cafeteria, he saw a kid playing around with a plate that had a Cornell logo on the side. When the kid spun it, Feynman noticed that the wobble of the plate compared to the spin of the plate somehow seemed to be related, but he didn’t know how. So he worked on it mathematically.

When he brought his results to Hans Bethe, Bethe said, “This is very interesting, but what’s the importance of it?” Feynman said it had no importance at all. It was just interesting. And, for the first time since the bomb had been used, Feynman was excited again, and decided never to work on anything again unless it interested him. Later, he said that the work he did with the spinning plate was important to the work he eventually won the Nobel Prize for.

Clash: Feynman was a great communicator. Effective communication is a mission of yours now, correct?

Alda: Yeah, it is, communicating kind of invades my life now, every aspect. I don’t write an email without thinking about whether I’m making clear the point I’m trying to make. How is this being heard by the person reading it? What do they think I mean?

It’s interesting. The danger of being misunderstood in electronic communication now is so widely felt. I think that’s the source of emojis, the smiling faces – you want to make sure you’re not being misunderstood. You may want to say “I’m just kidding” but without a tone of voice, the typed words may not come across as you meant them.

(Editor’s Note: In subsequent parts of this interview series with Alan Alda, we discuss his role in M*A*S*H, the journalist George Plimpton, fame, fear, UFO’s, Paul McCartney, scientist Madame Curie and more. Stay tuned, we’re just getting started.)