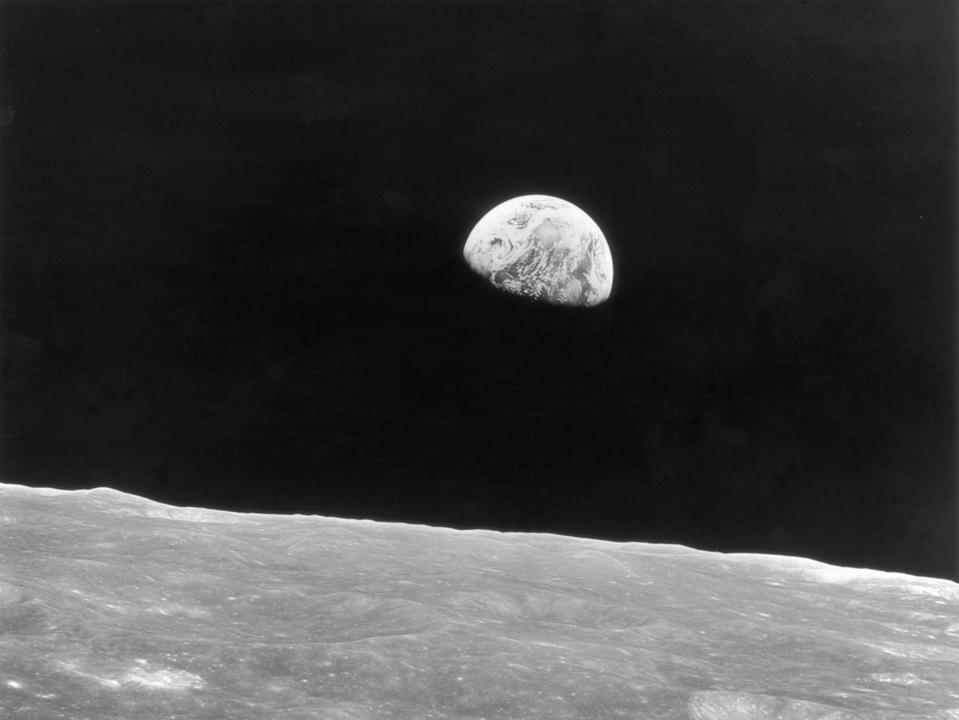

Last Christmas Eve marked 55 years since the publication of Apollo 8’s beautiful Earthrise photograph. It showed a sphere with swirls of dreamy blue and spidery white threads, partially obscuring land masses, mere smudges of orange and green.

It was the first time humans could see most of our planet rising over a lunar horizon.

To turn the camera back on our planet did more than just provide a stunning view of Earth. It forced us to consider the effects of our environmental footprint.

The iconic snap prompted serious consideration of humanity’s role in protecting our fragile planet. It inspired International Earth Day, one that a billion people celebrate each year, and helped start the environmental movement that even today connects and invites people to engage.

Renewable energy is one of the many factors that unite people in the movement. Solar remains key but there are many others. These are wind, bio-energy (made from biomass, a form of organic matter), waves, the tides, and geothermal sources.

All these alternative energy sources underscore the common good, something that cuts across religion and politics. Researchers have recently defined the meaning of this after surveying over 14,300 people. At the core they found four underpinning themes: objectives, outcomes, principles, and stakeholders.

For me, those themes resonate, particularly when we talk about solar energy.

The U.S. has significant progress to make, though, in maximizing the sun as a renewable energy source. Our World in Data shows that, per capita, the States consumes the most fossil fuels of all nations, a significant 63,836 kilowatt-hours per person.

Globally, only 29% of electricity is sourced from renewable sources, says the United Nations. It argues renewable energy is accessible, cheaper, healthier, creates jobs, and makes economic sense. How does the U.S. compare with generating power from solar? Research from the Solar Energy Industry Association (SEIA) shows we’re slowly tracking to achieve 30% by 2030.

While solar is one of the main resources to get to zero carbon emissions, humans have been harnessing the sun for power and warmth for longer than you’d expect.

Humans’ “unique relationship with the sun”, says the BBC, goes back millennia. It’s a narrative of survival, savvy, and has a sinister twist.

Fast forward to the early 1900s when the solar panel was invented, according to Dr Sugandha Srivastav, from the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. The scholar delved into historical records, dusty newspapers and modern analysis to surface the story of entrepreneur George Cove. He patented his solar energy contraption, which harnessed the photovoltaic effect to create enough electricity to power small household devices, she writes.

“George Cove was kidnapped and told to give up his patents and shut down his business. Contemporaries like Edison Electric were building out the power grid using coal-fired electricity and Standard Oil was consolidating its hold over the market by buying out any type of competitor at the time.

“Ruthless practices to drive out competitors were commonplace during this period of history,” writes Srivastav.

Cove’s company never recovered from that setback. Meanwhile, Bell Labs went on to invent the practical solar cell in the 1950s.

Solar energy is now one of a suite of renewable energy options. Solar energy is one of our planet’s most abundant energy sources. If technology could ‘bottle’ an hour and a half’s sunshine that hits Earth, we could power the globe’s energy consumption for a whole year, says earth.org.

Solar energy is coming out of the shadows and helping remind us of our positive connections with this star. At the heart of this movement is connections and not just to the power grid. Solar power helps link us with our communities, with policymakers, and with the very narrative of solar itself. The future of solar isn’t just about panels and power; it’s about purpose, passion, and people.

Solar’s advantages are long-term savings, low maintenance, and the obvious one of reducing dependence on non-renewable sources, according to SEIA.

There has been some pushback from utility companies, though. Regions that have a high number of domestic rooftop solar arrays can cause issues for the grid, causing supply unreliability and extra fine tuning of the infrastructure to manage the difference in load.

There are different ways of connecting to the grid, though.

Instead of having an array of isolated solar panels on a home or building, they are increasingly being linked to a microgrid to power a small community.

Other downsides of solar include high set-up costs, aspect and space constraints, the sun needs to shine for it to work, it’s not portable between established homes and its manufacturer could be greener. Battery storage as an offset makes sense. Using battery storage to offset these challenges is a sensible approach.

And, then there are snags to a greater uptake of solar in the U.S., the SEIA says. Strategic action for one. The SEIA’s latest report, Energizing American Battery Storage Manufacturing, comprehensively lays out the challenges and opportunities of domestic energy storage production.

The elephant in the room is that domestic production of solar components will slip behind demand by as early as next year – and that’s why strategic action is needed. Currently, China produces more than 80% of global solar cell exports and over half of lithium-ion batteries. Those batteries are the most popular form of storage renewable energy and will remain so for the next decade. (Lithium carbonate’s price dropped 80% last year, so it’s not surprising lithium mines have been closing or on the precipice of doing so since.)

How will your community, organization, or business be part of the ‘charge’ to boost solar for the common good of our country? Every bit helps.