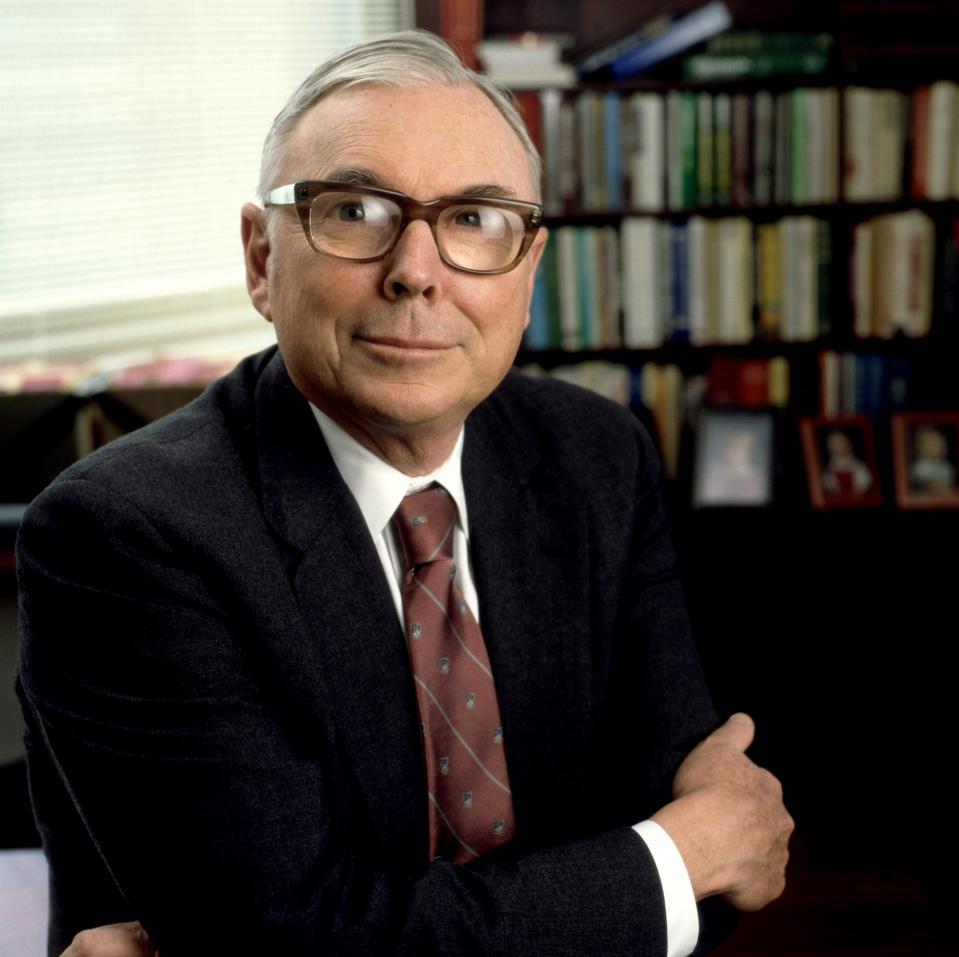

Charlie Munger, the vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett’s business partner, died November 28 — less than a month short of his 100th birthday. He was known for his dry wit and the depth of his wisdom. He was instrumental in Berkshire Hathaway’s success, which has been substantial as the company’s stock return of 19.8% annually from 1965 to 2022 trounced the S&P 500’s 9.9% return.

Over the years, volumes of Munger’s thoughts have been collected (such as Poor Charlie’s Almanack and The Tao of Charlie Munger), and those in the investment world revere his advice. Like others, Charlie’s sage insights have shaped my worldview. Below are the five Mungerisms that have impacted my thinking the most.

To Make Good Decisions, You Need A Latticework Of Mental Models

Munger pioneered the concept of mental models, which are conceptual structures that help us understand how the world works. They are bits of knowledge or wisdom we file away in our heads to help us make decisions. Here’s how he described mental models in a 1994 speech at USC’s business school:

“What is elementary, worldly wisdom? Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try to bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head . . . You’ve got to have multiple models—because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does . . . 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90 percent of the freight in making you a world-wise person.”

Creating a latticework of mental models requires study across various branches of knowledge. Munger considered himself a generalist and studied various disciplines beyond investing, including architecture, philosophy, physics, philanthropy, investing, and engineering. In Munger’s view, to make good decisions, you need to be able to draw on mental models developed from different disciplines. He knew a lawyer’s approach to an issue would differ from an engineer or an artist, so it made sense to develop mental models that span different specialties.

Developing a latticework of mental models is especially applicable to investing. This concept shaped my published book, The Uncertainty Solution: How to Invest With Confidence in the Face of the Unknown, which contains 35 mental models essential for successful investing. Through more than 25 years of experience in the wealth management industry, I’ve learned that when faced with uncertainty, great investors use mental models they’ve developed to help them maintain composure and avoid making decisions rooted in emotion.

Invert, Always Invert

“Invert, always invert.” – Carl Jacobi, 19th Century Mathematician

A compelling mental model Munger espoused is inversion, based on mathematician Carl Jacobi’s belief that a powerful way to solve math problems is to restate them in inverse form. Munger’s insight is that inversion is robust beyond mathematics; thinking is clarified by considering issues both forward and backward.

Most of us think of our goals in a forward direction, as in, “What do I need to do to accomplish my goal?” But it can be powerful to look at it backward by thinking about what we should do to ensure we won’t meet our objective. For example, if you want to lose weight, instead of just thinking about what you need to do to lose weight, it’s also instructive to ask yourself, “What would I do if I didn’t want to lose weight?” Those things might include not exercising, overeating, avoiding fruits and vegetables, and consuming many highly processed foods loaded with sugar. That inverted list can help you decide how to behave to achieve your goals.

I’ve previously written about how to use the concept of inversion to be a better investor in my article titled “Five Ways to Be a Terrible Investor.”

Know the Other Side’s Arguments

Munger cautioned against having an opinion unless you are fully educated on all sides of the issue, which is a specific application of the concept of inversion.

In 2007, he gave the commencement speech at the USC School of Law, and in his talk, he warned of “extremely intense ideology because it cabbages up one’s mind.” Whenever he “drifts toward preferring one ideology over another” he forces himself to consider the other side by telling himself, “I’m not entitled to have an opinion on this subject unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people do who are supporting it. I think only when I reach that stage am I qualified to speak.”

The underlying concept is that it takes work to have an informed opinion, and ideological thinking is lazy thinking. Instead of looking for facts that support your ideological leanings, having a valid opinion involves the often-painful task of researching facts that support the other side.

Beware of Making Decisions Based on Predictions of the Future

Given Berkshire Hathaway’s great success, you’d think that Munger and Buffett have an uncanny ability to predict the future. The opposite is true: a pillar of their success is their ability to admit they cannot predict the future.

Munger has noted that he’s “never been able to predict accurately. I don’t make money predicting accurately. We just tend to get into good businesses and stay there.” Moreover, Munger didn’t place much stock in experts’ predictions either: “People have always had this craving to have someone tell them the future. Long ago, kings would hire people to read sheep guts. There’s always been a market for people who pretend to know the future. Listening to today’s forecasters is just as crazy as when the king hired the guy to look at the sheep guts. It happens over and over and over.”

I think about Munger’s perspective whenever I’m tempted to click on some investment guru’s prediction about what the stock market will return or the path of interest rates. If Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett, two of the greatest investors of all time, don’t think they can predict the future or listen to expert predictions, why should I behave any differently?

To Be Wise, You Must Be a Reader

How did Charlie Munger become the sage that he was? Being a voracious reader played a significant role. Munger views reading as necessary for developing wisdom: “In my whole life, I have known no wise people who didn’t read all the time—none, zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren reads—and how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out.”

Munger thought reading beyond just one discipline was necessary to become a world-wise person. He noted, “You must know the big ideas in the big disciplines and use them routinely — all of them, not just a few. Most people are trained in one model — economics, for example — and try to solve all problems in one way. You know the old saying: to the man with a hammer, the world looks like a nail. This is a dumb way of handling problems.”

In Munger’s view, to be a great investor, you’d be better off reading 100 biographies than 100 books about how to invest. The key is to immerse yourself in ideas across disciplines to create your latticework of mental models. He admonished people to “Develop into a lifelong self-learner through voracious reading; cultivate curiosity and strive to become a little wiser every day.”

We’ll miss you Charlie!