In Part 1 of this series about Argentina’a Aconcagua, the highest mountain in the world outside of Asia (link below), we presented the sobering facts about the peak. Here, I take readers through my own personal experience leaving from Camp IV, at 19,300 feet, to the summit.

SUDDENLY IT’S MORNING, clear and cloudless. It’s the first time in a week we’ve seen the sun, having been hunkered down in our tents in blizzard conditions. I dress warmly with every piece of clothing I have. The temperature is below zero and will drop precipitously as we move higher. By 11 a.m. we have reached the 21,000-ft. mark, known as Independencia.

I’m intrigued by a group of Russian climbers using the small hut there as shelter against the wind. They are attempting to light cigarettes. I can barely breathe, yet they want to smoke. How can there be enough oxygen to light a match, let alone sustain burning tobacco?

The paradox quickly becomes too complicated. I write it off as a hallucination from oxygen deprivation. After a quick break for hydration, we slog on. From Independencia, we traverse a long snowfield, then up steep snow to the base of the Canaletta at 22,100 feet.

Thinking it has taken maybe an hour from Independencia, I begin to get excited. But when I look at my watch, despair sets in. It is already 2:30 p.m. Time is passing so quickly. I wonder if we will have enough, providing I have the strength, to get up what is called, even by Everest veterans, one of the tougher physical experiences in all of climbing.

I had been forewarned, but no warning can give adequate preparation for this structure. The Canaletta is simply the hardest thing I’ve ever attempted, both mentally and physically. It is 800 vertical feet of loose scree and boulders – a kind of hell up near heaven, if that makes sense. Three steps up, then a slide or two back, or a fall on my face, over and over, like trying to climb a down escalator. It’s now five to 10 gasps between strides, like sprinting 40 yards with each step.

The key is not to look up toward the top, seemingly a stone’s throw away but, malevolently, not getting any closer. My brain is hypoxic, depleted of oxygen, and playing tricks on me. For a while, I feel as if I’m watching myself from 10 yards away, struggling pathetically in some kind of slow motion, to ascend a stupid rock gully. What’s the point?

Another three-hour blur of suffering and I’m within the length of half of a football field from the top. There is no concept of time. I just know I have to put one foot in front of the other and soon I’ll be standing on the highest patch of ground outside of Central Asia. In fact, at that moment I’ll probably be the highest human on terra firma because it’s January, winter in the northern hemisphere, when Himalayan expeditions rarely climb.

My two guides later tell me it takes a full 20 minutes to cover that last 50 yards. Finally, at 5:30 p.m., I see the famous aluminum cross marking the summit. Rarely does one comprehend, at the moment, a defining experience, but I did. I’d spent years preparing, with failure the previous year, and nearly another month on the mountain suffering, and I tried to savor it.

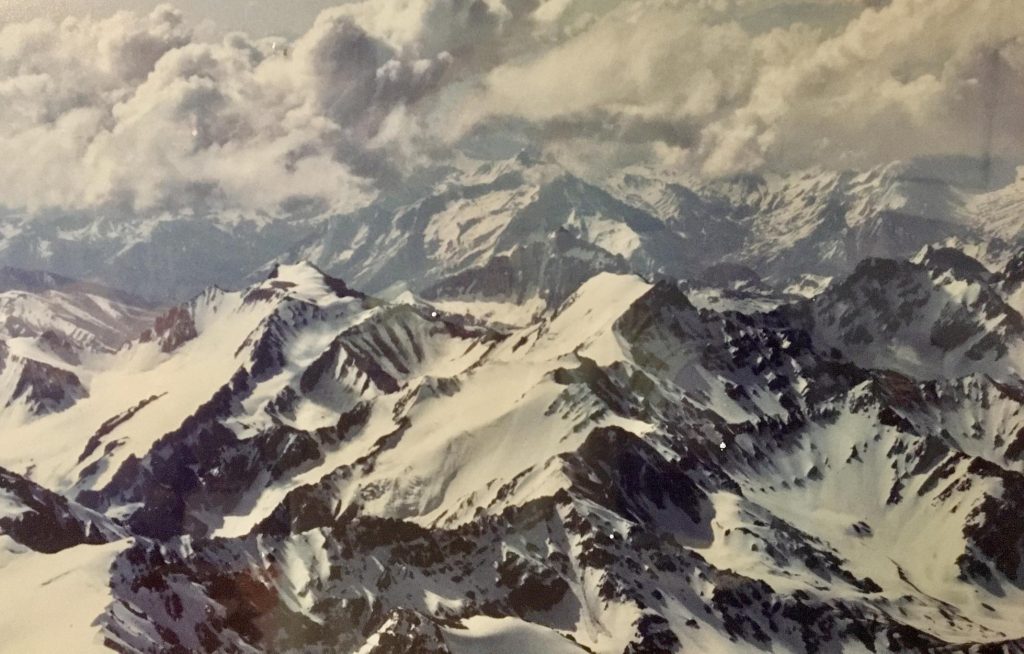

First, I snapped a ton of photos, taking in the surreal view. Next, I picked up some souvenir rocks. Just as I was getting used to the dream-like state, the guides tell me we must leave. In three hours we must descend what has taken nine to climb. If we don’t get back to the tents before dark, we risk losing our way and freezing to death in rapidly cooling night air.

It’s easy to see why more people die on descent than ascent. Increasingly feeble, I literally stumble down the Canaletta in a semi-drunken stupor. I’m so tired I just want to sit on the ground and fall sleep but my guides, in language not fit for print, urge me on. By 9 p.m., I’m safely back at Camp IV again, incredibly tired but grinning ear-to-ear.

I can assure you, I’m no Reinhold Messner, but on that particular night you would have had a hard time have convincing me otherwise.