The talk of a rare sudden stratospheric warming in the next two weeks is making the media rounds for several reasons. First it would be the first long cold spell of the season. Second, it has the potential to disrupt holiday travel and third, it would be well ahead of the typical midwinter window.

While online chatter is already predicting an imminent Arctic outbreak with images of storm tracks, early-season events behave differently and offer far less certainty. They are signals, not forecasts, and feed into the myths around SSWs.

How Is The SSW Related To The Polar Vortex?

An SSW is a high-altitude disruption of the polar vortex that can influence winter weather patterns. It can nudge the vortex off-balance or even split it, which sometimes allows colder Arctic air to spill southward. That said, every event behaves a bit differently, and the surface response depends on how the disrupted vortex evolves in the weeks that follow rather than the warming itself.

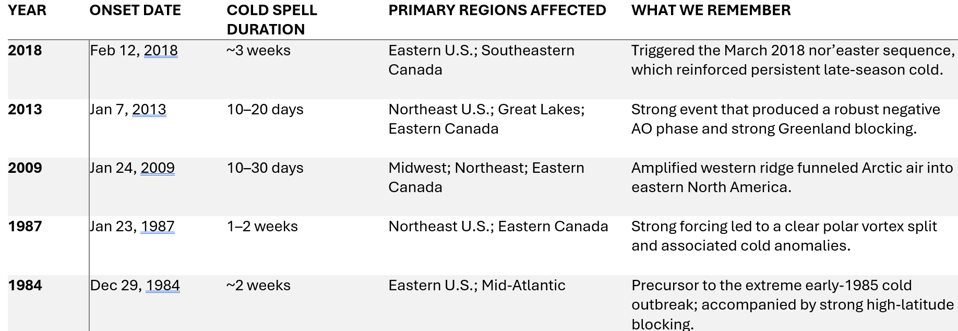

Early SSWs, in particular, fall into a small historical sample, making interpretation harder than many social media narratives suggest. With a potential November warming emerging, it’s essential to separate what science supports from typical myths around guaranteed cold or dramatic pattern shifts.

A central part of that connection is that the nature of the disruption strongly shapes the subsequent atmospheric response. Some SSWs displace the vortex off the pole, while others split it into multiple weaker circulations. These are two very different restructuring processes that can lead to very different surface outcomes. Early-season SSWs add another layer of uncertainty because the sample size is small and the jet stream is still transitioning toward its winter configuration.

Myth 1: A Polar Vortex Wobble Guarantees Cold Weather In North America

Public narratives often portray an SSW as a guaranteed pathway to widespread U.S. cold. The research tells a more nuanced story. Although SSWs can raise the likelihood of a negative Arctic Oscillation, which often favors colder conditions in parts of North America, the relationship is probabilistic rather than deterministic.

Roughly two-thirds of major SSWs have effects that reach the surface, but the outcome in any specific region still depends on the broader atmospheric pattern in place.

Early-season events are even less reliable indicators because the vortex isn’t fully established, and competing signals—ENSO, the Madden–Julian Oscillation, North Atlantic sea-surface temperatures—can amplify or dampen any SSW-related effect.

For cold to reach deep into the U.S. and persist, the atmosphere must support high-latitude blocking. An SSW increases the chances of that pattern but does not guarantee it.

Myth 2: All Warmings Work Downward The Same Way

Even if the late-November event is ultimately declared a major SSW, which requires both a sharp warming over the Arctic and a reversal of the polar vortex’s usual circulation high in the atmosphere, its impacts will still depend on whether that disruption works its way downward toward the surface where it matters to us. Some warmings stay trapped in the stratosphere with little effect at ground level, while others reshape the jet stream and influence weather patterns weeks later.

Myth 3: The Polar Vortex Locks In For The Winter

One common misconception is that once an SSW occurs, the rest of winter is locked into a particular regime. But early-season SSWs often behave differently than midwinter events. The vortex can, and often does, recover in December, reestablishing stronger westerly flow and reducing the likelihood of a second disruption.

Multiple major SSWs in one season are historically rare, and early events do not reliably increase or decrease that probability. Minor disturbances may still shape winter patterns, but their influence is different from the dramatic effects often associated with major vortex collapses.

This is an important forecasting nuance. An early SSW can shift the odds for certain pattern regimes in the following weeks, but it does not lock in a full-season outcome. Scenario-based planning, rather than firm predictions, remains the most scientifically sound approach.

How to Interpret The Late-November Event Responsibly

Late November sits outside the traditional window for major sudden stratospheric warmings, which typically peak in January and February. At this stage in the season, the polar vortex is still strengthening, and its structure is different than it will be six weeks from now. That matters because the conditions that usually help weaken the vortex—like how the winds and temperatures are arranged—aren’t fully in place this early in the season.

Because early events fall into a much smaller historical sample, the range of possible outcomes is wider and confidence is lower. In short, an early SSW creates more variability—not less—when it comes to downstream pattern expectations. Even when all the pieces fall into place, the outcome is far from guaranteed, and regional weather can still vary widely. This is why the popular myths around SSWs don’t hold up.

The latest ensemble outlook for the first week of December illustrates this uncertainty well, showing a partially disrupted vortex pattern that favors a trough in eastern Canada while keeping other areas less directly affected.

Why This Matters For Weather-Sensitive Sectors

For industries ranging from energy and agriculture to retail and logistics, early-winter pattern shifts can influence demand, staffing, and pricing. But overconfident interpretations of early stratospheric signals can lead to misaligned expectations. Scenario-based planning—rather than deterministic forecasting—remains the most scientifically sound and operationally useful approach.

The bottom line: SSWs are valuable indicators. An early SSW nudges the probabilities for certain pattern regimes in the following weeks, but it does not set the tone for the entire winter.