The next time the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee meets about the Fed interest rate is December 9-10. There will be a plethora of coverage in the media, from talking heads, across social media, and in corporate boardrooms and corner offices.

Much, if not virtually all, of it is “inside baseball” for the people and institutions who can make or lose significant amounts of money on these changes. For consumers, the results are either indifferent or negative. Here is what goes on.

What The Fed Interest Rate Controls

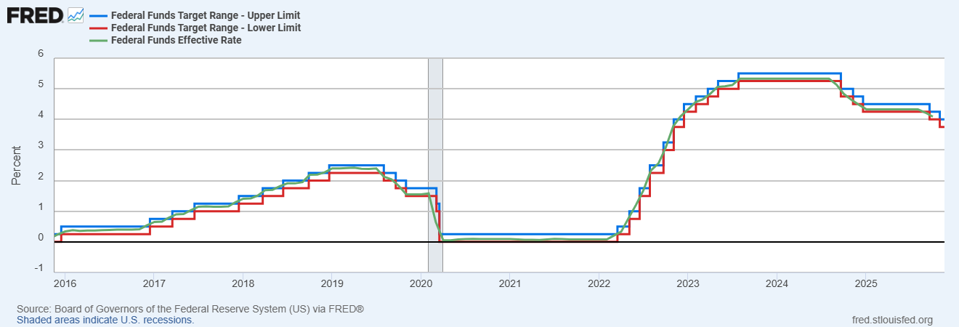

The Fed has direct control over what is called the federal funds rate. They set a target range — currently between 3.75% and 4.00% — which is how much banks should charge one another for overnight loans without any collateral backing them up. Then there is the effective rate, which is how market activity ultimately sets it. The below graph from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shows the upper and lower parts of the federal funds rate range and also the effective rate.

Many interest rates key off the federal funds rate, or FFR. For example, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, or SOFR, is a measure of overnight borrowing backed by Treasury securities as collateral. That type of borrowing is called the repo, for repurchase, market. The borrower sells Treasurys to the lender with the promise of buying them back at a higher predetermined price.

The FFR effectively becomes the upper limit for SOFR. SOFR, then, is also an influential interest rate, representing a virtually risk-free lending rate. Other rates based on it will take SOFR and add additional amounts of interest based on the amount of perceived risk of a given loan.

How The Fed Interest Rate Works

The FFR influences many types of interest rates, either directly or through its effect on SOFR. Not all: Home mortgages depend on the yield of the 10-year Treasury Note, also considered a risk-free basis of determining other interest rates, typically of longer durations.

Initially, the bonds come with a so-called coupon rate — the amount of interest guaranteed on an annual basis — and the par value, which is how much the bond is worth at maturity. The yield is the annual coupon payment divided by the bond price. The higher the bond price, the lower the yield. The lower the bond price, the higher the yield.

But even then, movements of Fed-set interest rates, along with other factors like the volume of government debt, influence expectations of investors and institutions. They think the economy will stay the same, get better, or get worse. When they think the economy will get worse, they frequently buy longer-term government bonds. The more demand from investors, the higher the prices of the bonds go. The higher the bond prices, the lower the yields.

The Fed’s decisions have immense repercussions throughout the financial world. Companies across the globe collectively can make or lose billions, maybe trillions, of dollars on what seem like small rate shifts. They have to pay more on a loan. Maybe they can refinance and operate under lower costs. There are derivative investments that help hedge against adverse changes.

It’s huge business. For consumers, not so much. If interest rates increase, they will percolate down and drive up the cost of living for consumers. Prices on goods and services, credit card and auto interest rates, will go up, creating inflation. If rates go down, it will take much longer for consumers to feel the benefit, and often, prices that have increased will remain elevated.

The next part will address what might happen when the Fed interest rate is up for change during the FOMC December decision on interest rates.