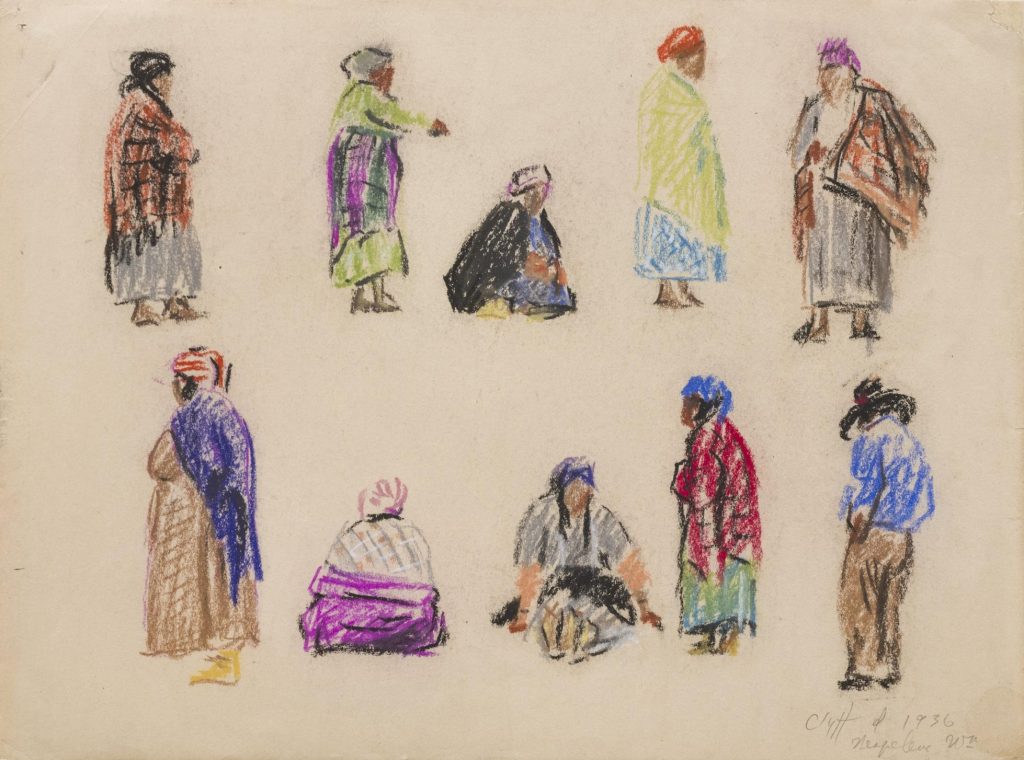

Clyfford Still (1904-1980) spent three summers in rural eastern Washington with the Colville tribal community from 1936 through 1938. He was a young art professor at Washington State College in Pullman, now Washington State University.

Still had not yet developed his enormous, earthy, jagged Abstract Expressionist canvases for which he’d become an icon, but their innovation was only a handful of years off.

After visiting the Reservation with his faculty supervisor Worth Griffin in 1936, the duo returned to form a summer art program the next year. Still was enamored by what he found there, forming relationships with the Colville people, soaking in the landscape, and creating more than 100 sketches, paintings, and photographs during the summers of 1937 and 1938.

While culturally distinct and diverse, the twelve bands of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation: Chelan, Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce, Colville, Entiat, Lakes, Methow, Moses-Columbia, Nespelem, Okanogan, Palus, San Poil, and Wenatchi, share cultural practices and 1.4 million acres of land.

Seeking to renew this historic relationship, leadership at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver reached out to tribal officials. If the Museum was interested in working with the Tribe, the Tribe requested those efforts be centered on the community’s children. What they came up with was an exhibition. Curated by kids from Coleville. At the Denver Museum.

For the past three years, Clyfford Still Museum curatorial and educational staff have collaborated with children ages three to 14 and their Colville teachers from partner schools on “’Tell Clyfford I Said ‘’Hi:’’ An Exhibition Curated by Children of the Colville Confederated Tribes.” Installed in all the Museum’s galleries, the presentation highlights the perspectives of Colville children on Still’s depictions of their home and ancestors, as well as the artist’s abstract works.

“(Children) approach artwork so confidently,” Nicole Cromartie, the museum’s Director of Learning & Engagement, told Forbes.com. “They don’t have all of these barriers that adults walk into looking at–especially abstract art–like do I need to have an art history degree? Do I need to have an art background? Surely I’m missing something. I want to ask questions. I don’t want to seem uninformed. Adults bring a lot of preconceived notions to looking at art that kids just do not, so they’re making sounds in response to the work. They’re relating the work to their daily lives. They’re making up fantastical stories about the work. That’s what we see at the Clyfford Still Museum on a daily basis and it’s the most joyful, bodily, incredible thing.”

That goes for all kids. The Coleville kids brought special insight and connections to Still’s artwork from the period.

“There was one incredible moment–we worked with about 100 (child) curators from three different schools–and we brought reproductions of the artworks to their schools, hung them up on gym walls to give them time to look and select their favorites,” Cromartie remembers. “One child said, ‘Oh my gosh, he’s a Red Star. I’m a Red Star. We’re related. This is so cool.’ Later the child said, ‘I didn’t know we were famous.’”

In Coleville, Still painted tribal members, the surrounding landscape, and the Grand Coulee Dam then under construction. Upon completion in 1941, altering the Columbia River in exchange for hydro power, it would stand as the largest concrete structure in the world, a distinction not surpassed until 2009.

“One of (kids’) favorite works of art was the construction of the Cooley Dam, and they had a lot say about that,” Cromartie said. “They were explaining, ‘This isn’t like this anymore, and this road has changed.’ They’re so familiar with the landscape and everything he was depicting in the 1930s.”

Museum staff hasn’t found anyone among the Colville Confederated Tribes who remembers Still visiting firsthand, nor have they come across any original Still artworks in the community.

On The Verge Of A Breakthrough

Clyfford Still Museum officials began working with Colville Tribal representatives in 2021 to learn more about the artist’s Coleville years. Years he has said were formative.

“We think this was a really important time; it was very soon after that that Still turns into the style that we know him for today,” Cromartie explained. “(Still) has a living daughter, Sandra, who has talked at length about the impact that this community had on her father, and that was something that he talked about, how important his time on the reservation was for his work.”

How, exactly, Still’s summers with the Coleville people influenced his work remains unidentified.

“What specifically did his time on the reservation do to inform the rest of his career? The short answer is, we don’t know,” Cromartie continued.

One of the Coleville students had an idea art historians never thought of.

“Another powerful moment in the development of the exhibition, the second gallery in the exhibition is called ‘Our Family, Our Culture,’ and it’s mostly works from the 1930s that (Still) made on the reservation, but there’s a huge abstract work in there,” Cromartie explained. “A fifth-grade student approached it and was like, ‘That’s a pow wow blanket,’ with full certainty. She said, ‘It reminds me of a pow wow blanket that my mom made.’ That was incredible. It was so definitive. There’s all of these art historians (wondering) how, what are the concrete ways (time on the Reservation influenced Still), and then this fifth-grade child is just like, ‘This is what this is.’”

Out of the mounts of babes.

Despite being born in North Dakota and growing up around Spokane, WA and Alberta, Canada, Still had no meaningful interaction with Native people or Native culture prior to his summers in Coleville. And he’d never return.

After bumming around in the early 40’s, he moved to New York in 1945 and split his time between there and California before basing himself in NYC for the 50s. He never liked it and moved to Maryland in 1961.

From Art Curators To Artists

Clyfford Still Museum officials look forward to continuing their relationship with the Tribe. They’re quick to point out that the exhibition is not the entire partnership. They hope to carry forward an unexpected offshoot of the recent collaboration.

“One of the direct impacts that we didn’t actually plan for as a part of this and we should have, but when we were working with the kids, and they were spending all this time with Still’s work, looking at his work, selecting the work, sharing their perceptions about the work, ‘Now we want to paint. Now we want to make art.’ Of course,” Cromartie remembers. “We ended up doing a full art day in the Nespelem gym, which is the same location that the original art program took place in the 1930s, but instead of it being WSU professors and students coming from all over the country and the Native people were just portrait sitters, this time, we flipped the script. There were Native teachers and artists and all of the Native students were participating in the workshops.”

The Museum also hopes to facilitate more visits from Coleville to Denver. Funding was secured for about 30 Tribal members to visit in advance of the exhibition.

“They were blown away by the color, the texture. It was almost like we betrayed them,” Cromartie said, laughing, the richness and scale of Still’s paintings, many over 10-feet a side, incapable of being captured in reproductions. “It was an incredible thing to see, not only their surprise at these works and the presence of these works, but also seeing them see their name on the wall under a quote that they said about the work. The ownership that they had walking into this museum for the first time was exactly what we want.”

The Clyfford Still Museum, located downtown adjacent to the Denver Art Museum, hosts nearly everything Still created, approximately 3,125 pieces representing 93% of his lifetime output, including the Coleville paintings and drawings, artworks seen anew through the eyes of descendants from the Coleville people who made such an impression on the artist almost 90 years ago.