Food prices have jumped 25% since 2021, while food consumption volumes are down over 5%. Inflation may be in the low single digits, but people are now buying a lot less food, with over 47 million Americans skipping meals or lining up at food banks. Grocery price inflation has driven an affordability crisis fueling food insecurity and economic anxiety.

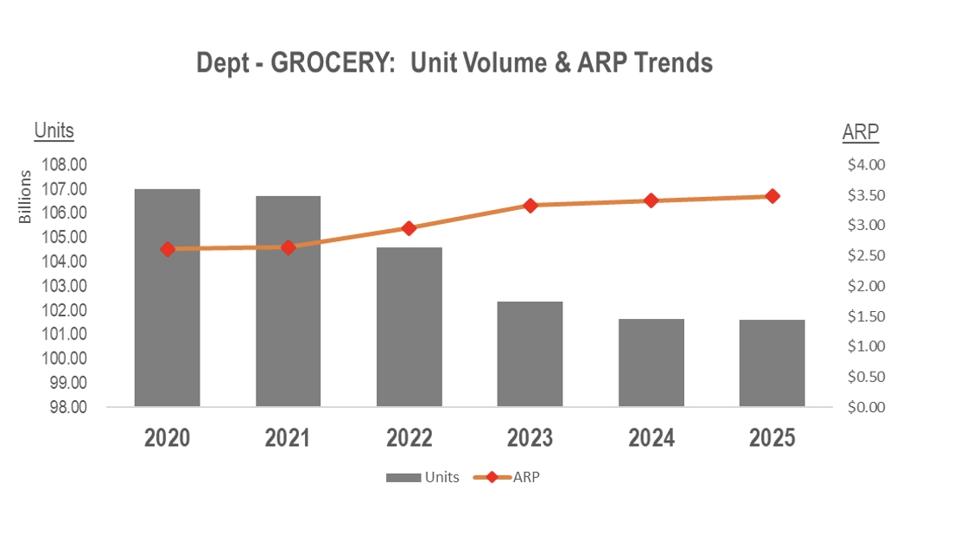

In 2025, grocers sold 13 billion fewer units of product than in 2021.

Grocery industry sales have jumped almost $225 billion since the pandemic ended. But that growth is all price inflation. Grocery prices outpaced the rate of inflation by several points from 2021-2023, with the gap growing as the CPI (consumer price index) cooled off.

Based on NIQ data exclusively shared with Forbes, the top 10 most consumed categories, including beef, soft drinks, eggs, milk, salty snacks and coffee, experienced an average price increase of 60% since 2019, with a 1.3% decline in unit volume. In 2019, a basket of the top 10 items cost $36. In 2025, $56. This far outpaces the nominal wage growth of 22% in the same period.

The increase in prices since 2019 is equal to or greater than the cost of doing business for most grocery stores.

Grocery store gross margins, more or less the markups they take on their wholesale costs, enable them to keep the lights on and pay for employees, rent, utilities, and taxes. Gross margins range from @22% for Kroger or Walmart and up to 35-40% for Sprouts, Whole Foods or your neighborhood co-op or supermarket. In order to bring retail prices down to 2019 levels, grocers would have to sell nearly everything at or below their wholesale costs.

There are a lot of reasons for recent price increases. Beef prices went up 14% from January to August 2025 because the beef cattle herd is the smallest in 75 years. The price of coffee has gone up 21% in 2025 because Brazilian imports like coffee began facing 50% tariffs last month. Apple prices increased 9.6% from September 2024 to September 2025 and 26% since 2019. Tomato prices started to jump after the end of a 30 year U.S.-Mexico trade agreement and began facing 17% tariffs in July. In California’s Oxnard region, intensified ICE activity has slashed agricultural labor by 20-40%. Vegetables increased 38.9% from June to July 2025 and total fruit and vegetables prices spiked 15% in the past year. The Trump Labor Department is worried that deportations could impact the food supply. And a Yale analysis estimates that tariffs will cost households over $2000 this year.

To combat such inflation, retailers are introducing more everyday low price private labels, selectively lowering prices with heavy marketing efforts, increasing chargebacks, fees and markdown requirements from suppliers, and using AI to “optimize” deals and targeted pricing. But much of this will just be rearranging deck chairs when it comes to affordability.

Market consolidation and the resulting profiteering have been the biggest drivers of price inflation and the resulting decline in food consumption.

Just six grocers control over 60% of sales nationally. Walmart has increased market share since 2020 by almost 2 points and has over 60% market share in dozens of metro areas. In Portland and Seattle, the top 2 chains control 50% of sales. In Chicago, the top 3 chains control 50%, and in Southern California, the top 2 control 40%. In Detroit, Atlanta, Dallas, Arizona and Denver, the top 3 grocers control 60%. In all cases, Walmart, Kroger and or/Albertsons are #1, 2 or 3.

On grocery shelves, most categories are heavily consolidated. Four or fewer corporations controlling 60-85% of meat processing, 93% of soda, 80% of candy, 75% of yogurt, 72% of breakfast cereals, 60% of snack bars, 66% of frozen pizza and 60% of bread.

Some of the highest price inflation has been in the most highly consolidated categories. Since 2021, meat prices are up 30% and consumption volumes are down 8%. Meat prices made up the largest chunk of price increases in 2021 and 2022. Four conglomerates control up to 85% of meat processing and their profits surged by 120%, and net income by 500% in that timeframe.

Egg prices are up 130% since 2021, and volumes are down, due to avian flu, low pullet supply, and record profits from market leader United Egg Producers.

Soft drink prices are up 46% since 2021 and volumes are down 1%. The top 3 companies control over 80% of sales. In 2021, Pepsico announced its first major price increase of 5%, enabling $8 billion in net income and over $5 billion in shareholder dividends by early 2022. Coca-Cola soon raised prices, leading to a 15% net income increase. Pepsico increased prices again and in 2023, took in $91 billion in revenue, up 35% since 2019. As the CEO of Pepsico stated in 2023, “I still think we’re capable of taking whatever pricing we need.”

And in 2022, the 4 companies who control 70% of French fry production raised prices within a week of each other, a tater tot cartel being sued by independent grocers for price gouging. French fry prices have increased by 56% since 2019 and units are flat.

From April 2019 to summer 2022 Walmart raised thousands of prices above the rate of inflation. At Albertsons stores in that timeframe, prices on pantry items jumped by over 75%. On the stand testifying under oath during their Albertsons merger FTC trial, Kroger executives admitted to raising milk and egg retail prices above the rate of cost inflation. Between 2019 and 2024, Kroger’s net income grew by over 92 percent, and Albertsons’ net income grew by over 108 percent. And from 2018 to 2022, Kroger and Albertsons took out a combined $15.8 billion in cash for stock dividends and buybacks. Walmart took in record profits throughout the post pandemic years. A March 2024 report by the Federal Trade Commission noted that market leading retailers saw their revenues outpace their costs by more than 6% in 2021 and 7% in 2023. The European Central Bank, the IMF, the OECD and the European Commission, as well as the Economic Policy Institute and Groundwork Collaborative all published studies on how profits were driving inflation.

Those profits are still being paid for today through higher grocery prices.

And so, food is much more unaffordable, consumers are buying much less food and food insecurity is skyrocketing.

Not surprisingly, inflation is now rated as the biggest risk to the U.S. economy and 90% of U.S. adults are stressed about grocery prices. The CEO of GoFundMe said the economy is so bad that people are crowdfunding for groceries. Rising grocery costs are forcing 45% of Virginia families into debt. The grocery industry is now having a post-profiteering hangover and is getting rocked with mergers and acquisitions (Mars, Kellanova, Ferrero, Kellogg’s), disaggregations (Kraft Heinz), layoffs (Target, General Mills) and store closures (Kroger, Albertsons).

The grocery industry had some blockbuster years that fueled inflation. Now, industry can’t solve the affordability crisis. But there are other solutions at hand.

Regulators can start by enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act.

This could ensure a more fair and diversified market for workers, suppliers, consumers and independent neighborhood grocers by policing how bigger chains demand low costs and better payment terms at the expense of competitors. And national anti-price gouging regulation could give consumers more control over how high grocery prices can go. But these pricing regulations alone won’t solve for affordability.

SNAP, or federal food subsidies, can be an affordability solution.

SNAP currently accounts for about 9% of grocery industry revenue, or $100 billion a year. But strict means testing has made the program ineffective at preventing food insecurity. Current SNAP benefits add up to just $190 a month for an individual and $351 for a family of four, less than three weeks of groceries for anyone wanting to eat healthy. The solution would be to supercharge SNAP. First, make all fresh produce free. This would be about $90 billion a year. Next, subsidize the difference in total retail prices between 2019 and 2025, or about $225 billion. This adds up to about $400 billion, which may sound like a lot, but is just the growth in defense spending between 2015 and 2025.

And another solution to affordability, public sector grocery stores, hit the mainstream with Zohran Mamdani’s successful mayoral campaign in New York City.

Public grocers already exists at scale, in the U.S. military commissary system. The commissary uses a cost plus 2% markup, and taxpayers subsidize the gross margins so that retail prices are 20-30% lower that the market. The commissary generates over $5.6 billion in annual sales and is well-loved by U.S. service members, who will live near bases to shop there even after they retire. A retired army officer summed it up for Forbes in an interview, “Always less expensive. Good food. There should be a push for public PX style grocers across the country.”

Public grocers could also leverage existing advantages of scale, such as in New York City where public institutions purchase over $500 million in food a year, much of which uses value-based purchasing frameworks which prioritize sustainability and fairness. The federal government already purchases close to $8 billion in food annually. Public grocers could be the backstop the food system needs, especially with Robinson Patman fair pricing enforcement.

Such public efforts for affordability are already viable around the globe. India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) distributes subsidized food to India’s poor. Istanbul’s small, neighborhood based non-profit stores sell food at or below cost. Bulgaria has announced plans to create a network of 1,500 public discount stores. Mexico has 25,000 basic goods outlets as well as 50 publicly-owned supermarkets that are being revitalized. And Brazil has expanded cash transfers, a universal school meals program, an increase in the minimum wage, public procurement from family farmers and has granted every Brazilian the right to food. Over 83% of Americans also think that food should be a human right.

Faye Guenther, President of UFCW 3000 agrees, “Over the last four decades the supermarket industry has become highly concentrated and the power of workers and consumers has been dramatically reduced. We need a public option in the supermarket industry—stores that are focused on providing healthy food in our communities, while providing jobs with good wages and benefits.”

Grocery profiteering and the resulting price inflation have fueled an affordability crisis. Antitrust and anti-price gouging enforcement that levels the playing field, expanded consumer subsidies and a large scale public grocery sector are the solutions that can make good food affordable again. Inflation has made public groceries inevitable.