The Americas.

Plural.

Not to be confused with America. Singular. One nation, sea to shining sea, bracketed north and south by arbitrary political boundaries. On this side, you’re American. On that side, something else.

Two hundred and fifty years of America has nearly obliterated thousands of years of the Americas. The natural and casual movements and migrations of people and cultures throughout the Americas occurring before colonization, before ideas of personal property and ownership and borders and walls and foreigners and citizenship ground that freedom and exchange nearly to a halt.

The Americas.

Not only the United States of America; North America, South America, Latin America, the Caribbean.

What are the Americas? Who are the Americans? Who dictates and defines those terms?

Exhibitions across New York–the Americas’ great epicenter for Americans from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic Circle–pick up those questions.

“Whose America?”

“Whose America?” at the National Academy of Design examines the United States’ relationship to the history of ‘America’ in all its pluralities, challenging the idea that ‘America’ has ever been synonymous with the United States.

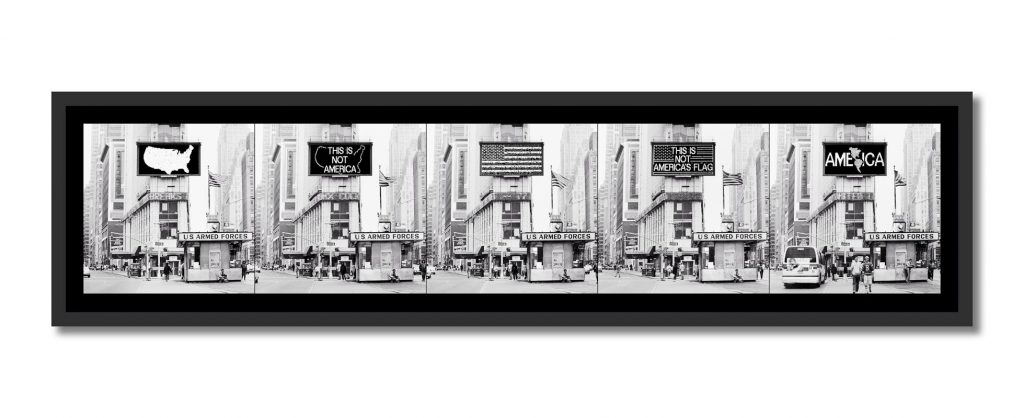

Alfredo Jaar’s (b. 1956) A Logo for America (1987) draws attention to this legacy of ‘America’ being used to refer only to the United States, a country claiming the identity of an entire continent–two of them–as its own; ‘America’ being used to simplify and reduce a vast part of the world into a single, nationalistic sentiment.

Related to Jaar’s complication of cartographic representations of the United States as being one and the same as ‘America,’ Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s (1940-2025; Salish member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) Unhinged (Map) (2018) entirely repositions the U.S. map amidst the Caribbean and Central America. In place of its typical geographic prominence, Quick-to-See Smith has rendered it as being in motion and without stability.

As the inaugural exhibition of the National Academy’s year-long bicentennial celebration, “Whose America?” draws on the Academy’s history as one of the founding arts institutions in the United States. The National Academy is the leading honorary society for visual artists and architects in the United States and the nation’s oldest artist and architect-led organization.

The Academy has 500 living academicians selected by their peers in recognition of extraordinary contributions to art and architecture in America–the country; the best of the best from art and architecture embodying the Academy’s shared belief in the power of art and architecture to change society and enrich lives.

“Whose America?” (through January 10, 2026) draws on the Academy’s eclectic roster of National Academicians with vastly different experiences of diaspora from throughout the Americas. Heavyweights in their fields including Dawoud Bey, Teresita Fernández, Charles Gaines, Carmen Herrera (1915-2022), Glenn Ligon, Maya Lin, Faith Ringgold (1930-2024), Shahzia Sikander, Kay WalkingStick (Citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and Anglo) and Nari Ward. The exhibition also highlights work by dozens of non-Academician artists from countries across the Americas including Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Puerto Rico.

“We AmeRícans”

Perhaps no place feels the Americas/American–United States of–duality more acutely and as more a part of its daily experience than Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico became a U.S. territory in 1898 following the Spanish-American War. Territory, not a state. More than three million Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, but U.S. citizens without representation in the U.S. government. They can’t vote for president. They don’t have senators, and their one representative to the House in Washington, D.C. has no voting power.

Puerto Rico is subject to U.S. laws and uses U.S. currency. Puerto Ricans pay U.S. taxes and are eligible for some U.S. social benefits. Not all.

In its relationship to the United States of America, Puerto Rico is half pregnant.

“We AmeRícans” at Claire Oliver Gallery brings together multiple generations of Puerto Rican and Puerto Rican-descendant artists whose works reflect the history, resilience, and cultural contributions of the Puerto Rican community in New York City and beyond.

The exhibition takes its title from pioneering Nuyorican poet Tato Laviera’s celebrated 1985 poem “AmeRícan.” His writing embraces cultural hybridity, identity, and pride:

walking plena-rhythms in new york,

strutting beautifully alert, alive

many turning eyes wondering,

admiring!

It continues…

defining myself my own way any way many

many ways Am e Rícan, with the big R and the

accent on the í!

Celebrating the vibrance Puerto Ricans bring New York…

speaking new words in spanglish tenements,

fast tongue moving street corner “que

corta” talk being invented at the insistence

of a smile!

The hope…

we blend and mix all that is good!

The future…

integrating in new york and defining our

own destino, our own way of life

The exhibition (through January 3, 2026) draws historical grounding from the Great Migration of Puerto Ricans to New York, a transformative wave beginning in the mid-20th century when hundreds of thousands migrated from Puerto Rico to the mainland. Factors such as economic hardship, increased job opportunities, and the accessibility of air travel fueled this movement, making New York City the largest Puerto Rican cultural center outside of the island. By the mid-1960s, more than one million Puerto Ricans had settled in the United States, with the majority residing in New York City.

NO+ (“No more”)

“Lotty Rosenfeld: Disobedient Spaces” at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery is no celebration. Sixteen years of authoritarian right-wing rule, torture, disappearings, and elimination of rights and freedoms will do that to a person. To a nation.

The artist is Lotty Rosenfeld (b. 1943, Santiago; d. 2020, Santiago). The nation, Chile. The dictator, Pinochet, boosted to power in 1973 with U.S. assistance, a military coup overthrowing the nation’s democratically elected left-wing government. America, the country, has a long history of intervening on behalf of pro-capitalist dictators in opposition of democracy across the Americas–plural.

Rosenfeld celebrated the imagination as the antidote to systems of control, be they patriarchal, dictatorial, capitalistic, or colonial. She fought back. She was a crucial player in a Latin American network merging activism with poetry, using her expertise as a graphic designer and printmaker to inscribe the phrase “No+” in public spaces.

NO+ (“No more”) served as a rallying cry across Chile, a signal of resistance during Pinochet’s dictatorship.

NO+ (“No More”).

The artwork and message could be customized by fellow resistors.

No more dictatorship. No + Dictadura.

No more torture. No + Tortura.

No more fear. No + Miedo.

NO+ lives on in today’s Hands Off movement across America. Singular.

Hands off public lands. Hands off the Department of Education. Hands off USAID. Hands off Medicare. Hands off Medicaid. Hands off Social Security. Hands off the Smithsonian Institution. Hands off the Centers for Disease Control.

In the bleakest of times, Rosenfeld’s oppositional artistic voice kept alive spaces for dissent, influencing the cultural and political imagination that ultimately set the stage for successful large-scale resistance movements.

Ironically, the artwork of a fighter for freedom of thought and speech and against fascism and violent authoritarian dictatorship on view at an institution disgracefully now defined by its attack on freedom of thought and speech and capitulation to fascism and violent authoritarian dictatorship. A hero at a university led by cowards.

One artist risking her life to resist evil. Columbia University, with its vast Ivy League wealth and power and privilege, unwilling to risk anything, bending its knee to evil.

Visit the Wallach Gallery through March 15, 2026, in respect to Rosenfeld and then spit on the ground upon exiting campus.

Creolization

At Sargent’s Daughters gallery, Yaron Michael Hakim’s (b. 1980 Bogotá, Colombia) “Antecedents” shows off new paintings and sculptures. Adopted from Colombia as an infant, Hakim draws on his personal history in a body of work considering the interconnected stories we tell about ourselves, our families and cultures.

While past artworks have focused on his experiences, “Antecedents” (through December 6) foregrounds other Colombian adoptees he has interviewed about their adoptions and reunions with birth families. In these paintings, their stories become surreal portraits and narrative scenes. Human figures blend and intertwine with tropical plants against the real and imagined landscapes of Colombia.

What is true. What is thought to be true. What is desired to be true.

Throughout “Antecedents,” Hakim draws on the concept of creolization as explored by Martiniquais writer and thinker Édouard Glissant. Glissant wrote that creolization occurs when “the most distant and most heterogeneous elements possible [are] put into relation with each other. This produces unforeseeable results.”

This produces the Americas. Plural.

And America. Singular.