I often tell people that the atmosphere doesn’t lie. It records everything we do, long after we forget. And today, it’s telling a clear, measurable story. Last week, the World Meteorological Organization issued their 2025 Greenhouse Gas report. It showed that global carbon dioxide levels surged by 3.5 ppm between 2023 and 2024, marking the largest annual jump since modern measurements began in 1957.

For those of us who have tracked the atmosphere over decades, that number speaks volumes. It’s not just another data point, but a milestone in the steady rise of greenhouse gases that scientists projected long ago would reshape weather, sea levels, and storm behavior.

When I first began following climate research in early 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and other leading scientists made three core projections: carbon dioxide levels would surpass 400 ppm early in the 21st century, global temperatures would rise by roughly 0.2 to 0.3 °C per decade, and heavier rain, higher seas, and stronger storms would follow. Those forecasts seemed bold at the time, yet today’s measurements show just how accurate they were.

That consistency led me to revisit other foundational projections from the 1990s and early 2000s to see how those early forecasts compare with the realities we observe today.

Atmospheric CO₂ Levels Remain On Target

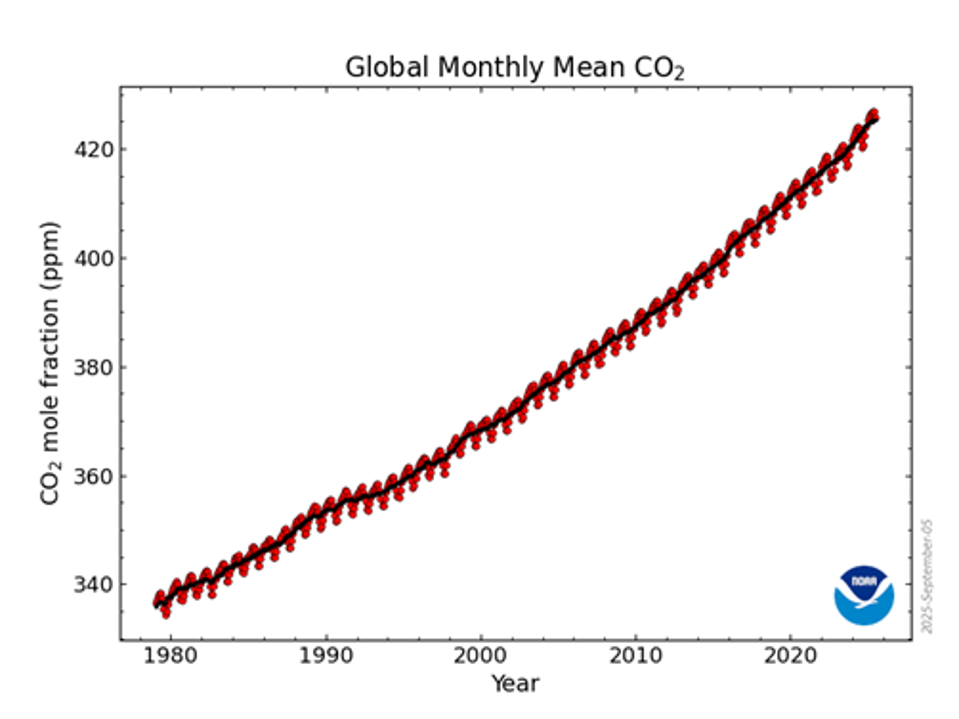

Let’s start with CO₂ because it’s the most fundamental signal of how human activity is altering the climate. In the early-1980s, climate models projected that if global emissions continued their current path, atmospheric CO₂ would reach about 405 ppm by the mid-2010s.

That forecast was impressively accurate. By 2016, CO₂ measured 404 ppm, and by 2023, it exceeded 420 ppm. The daily reading at the Mauna Loa Observatory, the baseline station for the long-term monitoring of atmospheric gases, aligns almost perfectly with these predictions.

The projections are right on schedule, though not in a good way. The rise in CO₂ is the driver behind nearly every other change we’re experiencing.

Global Temperatures Hold True To The Science

Looking back at early IPCC reports, scientists noted that if emissions continued to rise, the planet would likely warm by the early 21st century, and that outcome has largely occurred. The World Meteorological Organization confirmed that 2024 was the warmest year on record,

As a meteorologist, I see that warming is not just in annual averages but also in the behavior of the atmosphere . Heat waves are longer. Winters are milder and ocean temperatures are shattering records. The pattern isn’t random. It is cumulative.

Heavier Rainfall And Flooding Reflect A Wetter Atmosphere

One of the more profound, and increasingly visible, outcomes of a warmer planet is a wetter atmosphere. Warmer air can hold about 7% more water vapor for every 1°C of warming, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing play out.

Back in 1989, researchers warned that rising global temperatures would lead to heavier and more frequent extreme rainfall events. Across much of North America and Europe, the frequency of the heaviest rainfall days has increased markedly compared to mid-20th-century levels, with U.S. data showing a clear rise in the frequency and intensity of extreme single-day precipitation events since the 1980s.

For those of us in weather and risk management, this shift has moved from a scientific discussion to an operational reality. Flooding isn’t just a seasonal concern anymore. It’s a recurring variable in planning. Municipalities are straining to modernize drainage systems designed for a different era. Logistics managers are re-evaluating routes and schedules around storm frequency, and insurance providers are recalculating flood exposure maps that once seemed reliable.

What’s changing isn’t necessarily how often it rains, but how much falls at once. As the atmosphere holds more moisture, each storm has the potential to deliver heavier downpours, overwhelming systems built for lower extremes.

Sea Level Rise Matches Early Predictions

The global mean sea level in mid-1990 was projected to rise by roughly 8 centimeters by 2020. Modern satellite altimetry and tide-gauge data show a rise of about 9 centimeters over that same period — a near-perfect match.

The main surprise was how quickly ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica accelerated. The original projections captured the effect of thermal expansion in warming oceans accurately but underestimated how much additional rise would come from melting ice sheets. Even so, the total increase in sea level remains close to what scientists projected, though for slightly different reasons.

For business leaders, the implications are immediate and tangible. Real estate values in coastal zones are adjusting as buyers increasingly factor flood exposure and elevation into their purchasing decisions. Infrastructure planners are accounting for “sunny day” tidal flooding, something once considered a fringe risk. Insurers, port operators, and supply-chain managers are all recalibrating around a higher baseline of sea-level risk.

Hurricanes And Extreme Storms: Not More Storms, But More Power

When climate scientists first examined the potential effects of warming oceans on tropical cyclones, their conclusion was cautious: the total number of storms might not rise, but the strongest ones would get stronger. The data has since borne that out.

Over recent decades we’ve observed an increase in the proportion of tropical cyclones reaching Categories 4 and 5 and more frequent rapid intensification events, where storms ramp up from mild to catastrophic much faster. For example, Hurricane Milton’s rapid intensification to Category 5 in October 2024 saw wind speeds jump 95 mph in just 24 hours, more than twice the conventional threshold for rapid intensification.

We are seeing a more recent example of this with the rapid intensification of Hurricane Melissa. Predicted to be the strongest storm on Earth in 2025, the Category 5 storm expected to impact Jamaica and other Caribbean islands. Forbes contributor Marshall Shepherd does an excellent job explaining how Melissa evolved into a super storm.

Energy producers, insurers, and logistics providers are recalibrating exposure not just to “storm frequency” but to storm velocity; how fast risk escalates once conditions align. The operational window for response is shrinking, and resilience planning now hinges on anticipation, not reaction.

Moving From Prediction To Preparation

When I think back to the skepticism in the early days, myself included, it’s hard not to be impressed by how close those early projections came. These scientists were working with limited computing power, incomplete datasets, and models that had to make many assumptions. Yet they accurately captured the direction and magnitude of the changes we’re now experiencing.

This is a proven warning that today’s business and policy leaders should treat today’s verified climate trends as tomorrow’s planning inputs.

The same predictive frameworks that anticipated CO₂ and temperature increases can now be harnessed to anticipate where, when, and how climate volatility will reshape markets, infrastructure, and supply chains.