American financial institutions face an escalating challenge: criminals are systematically weaponizing US bank accounts to move, disguise and launder illicit funds. Over the past five years, evidence from both FinCEN data and underground markets shows that these accounts, once mere targets of theft,are increasingly being repurposed as tools for large-scale money laundering.

FinCEN’s suspicious activity reports (SARs) confirm that this trend is accelerating. Over the past five years, filings tied to suspicious bank accounts and fraudulent wire transfers have surged to historic highs. At the same time, underground markets on Telegram and the darknet openly advertise ACH wire transfer services. Together, these official downstream filings and upstream underground signals reveal how bank accounts are being systematically weaponized — not only as targets for theft, but as infrastructure for laundering illicit money at scale.

This is the second of a two-part series examining fraud in America. The first part focused on the consumer side of the threat landscape; this installment turns to how stolen funds and criminal proceeds flow through our banking system.

FinCEN Data on Suspicious Bank Accounts and Wire Transfers

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), is the U.S. Treasury’s financial intelligence unit. Part of its mission includes collecting and analyzing reports from banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions—most notably Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs). FinCEN uses this data to spot patterns of fraud, money laundering, terrorist financing and other crimes, then shares its findings with law enforcement and other regulators. Portions of SAR data are published via the publicly accessible SAR Stats, which aggregate filings and reveal trends by activity (e.g., check fraud, identity theft, account takeover, wire fraud, or scams), geography, and filer type.

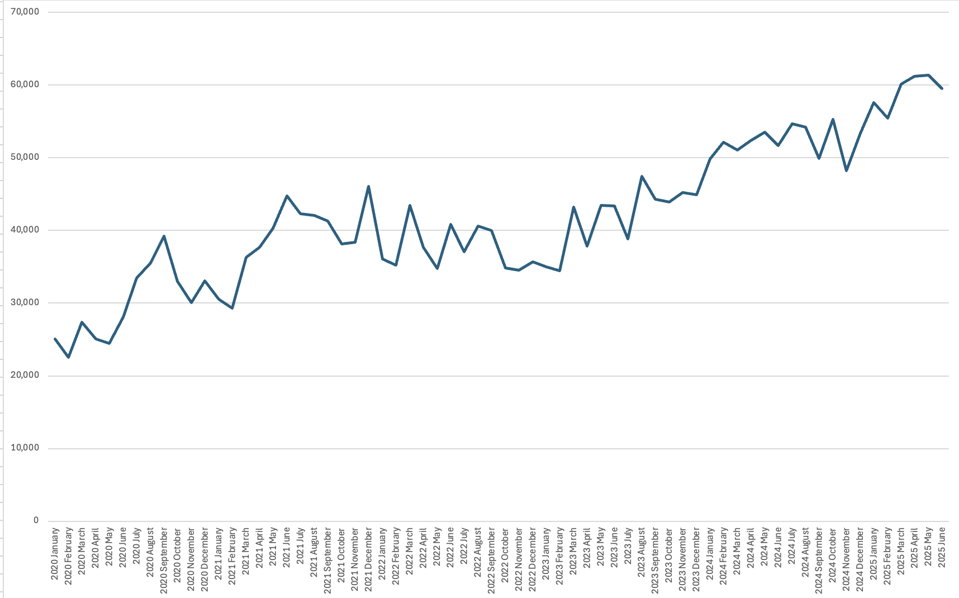

Wire transfers are deemed suspicious when they involve illicit funds, BSA evasion, or facilitation of criminal activity. SAR data shows that suspicious wire and EFT activity has grown steadily from a baseline of 22k–30k monthly filings in early 2020 to record highs above 60k by mid-2025. After an 80% increase through 2020–2021, reports plateaued at elevated levels in 2022 before climbing again in 2023 and breaking decisively into the 50k–61k range in 2024–2025 — more than double pre-2020 volumes. Unlike check fraud, which has begun to cool, wire-related SARs continue to rise, cementing their role as one of the fastest-growing channels exploited for large-scale financial crime.

A similar pattern appears in SARs citing suspicious sources of funds. While FinCEN does not provide a rigid definition of what constitutes “suspicion” in this context, it frames it as a reasonable basis to believe that a transaction may involve criminal proceeds or be linked to other illicit activity. Indicators commonly cited include the absence of a clear business or legal purpose, unusual or unjustified complexity, evidence of money laundering patterns, inconsistent customer behavior or identification, the use of aliases, and transactions tied to high-risk jurisdictions.

SARs citing source-of-funds suspicion have more than doubled since 2020, reflecting growing concern over transactions potentially linked to illicit proceeds. Filings averaged 30k-45k per month in 2020, climbed through 2021 (peaking at 56k in December), held the 47k-56k range through 2022, then surged in 2023, hitting 68k in spring and spiking to over 83k in August, marking a decisive structural break. Volumes stayed elevated in 2024 and through 2025 to date, reaching a record 87k in June 2025 — over twice the 2020 baseline.

Perhaps the most concerning development is the sharp rise in SARs identifying funnel accounts. These are individual or business accounts that receive multiple cash deposits — often structured just below reporting thresholds — in one geographic area, with the funds quickly withdrawn in another, leaving little time between deposit and withdrawal. Over the past five years, filings linked to funnel accounts have grown steadily, underscoring their expanding role in laundering schemes. In 2020, reports averaged 1,300–2,600 per month, climbing past 3,100 in 2021 before easing somewhat in 2022–2023. By late 2023, however, activity accelerated again, with 2024 filings consistently above 3,000 and spiking to nearly 4,800 by year’s end. The surge has only intensified in 2025, surpassing 5,000 per month early in the year and hitting a record 7,099 in May — more than four times the 2020 baseline.

Suspicious Bank Account and Wire Activity in Underground Markets

Online fraud market data is drawn from illicit forums and darknet marketplaces where criminals trade stolen checks, personal information, forged documents, and fraud-as-a-service tools. Unlike SARs, which are filed by banks and other regulated institutions after suspicious behavior has been detected, fraud market data is unstructured, real-time, and often reveals what criminals are planning or selling before those schemes ever reach a financial institution’s radar. In this sense, underground markets provide the upstream view—supply-side signals of what fraudsters are buying, selling, and testing—while FinCEN offers the downstream view, documenting how those activities manifest in the financial system. Together, they link criminal intent to measurable financial impact.

One of the most striking insights from the online underground is the growing demand for bank accounts that can receive fraud proceeds via wire transfer. Criminal senders aren’t simply looking for any account—they often seek out “aged” accounts, meaning accounts that have been active for at least a year and therefore less likely to trigger immediate red flags with financial institutions. The underlying premise of these senders is that money transfers for aged accounts will be less likely to raise red flags by the receiving bank’s fraud team.

Posts from fraudsters frequently outline specific terms: how much money they intend to wire, how the funds will be split between sender and receiver, and even the preferred bank brand or account type (for example, business versus personal accounts). In some cases, requests explicitly list desired transfer amounts—ranging from a few thousand to much larger sums—highlighting both the scale of operations and the calculated effort to minimize risk. These marketplace postings show that compromised and rented accounts are no longer treated as generic commodities but as tailored financial infrastructure designed to launder illicit proceeds efficiently.

Some senders on underground platforms post videos of completed transfers as proof-of-performance. In one example, a video shows a $50,000 transfer sent to a recipient identified as “Maria.” Another video highlights a sequence where more than $25,000 was wired into an account, followed by a withdrawal of $20,000 shortly afterward—leaving the account holder with a $5,000 profit as their share of the arrangement. These clips advertise both mechanics and payouts, underscoring how professionalized and transactional these underground arrangements have become.

On the supply side, vendors advertise cross-border wire transfer services. Some are highly detailed, naming the bank brands and transfer channels they use, while others remain deliberately vague to avoid drawing scrutiny. Fees are typically structured as a percentage of the amount being wired, meaning larger transfers command higher costs. Interestingly, certain vendors openly market their services as money laundering solutions, emphasizing their ability to disguise the illicit origin of funds, while others avoid such direct language but clearly operate within the same ecosystem. Together, these offerings highlight the extent to which underground actors are positioning themselves as global, on-demand payment processors for criminal proceeds.

In one example, a vendor advertised access to a meat packing company’s corporate account and showcased a $400,000 transaction. Commercial accounts with large, frequent activity help conceal illicit flows, mirroring funnel-account patterns of structured deposits and rapid withdrawals across geographies we see in FinCEN SARs. This underscores how underground vendors deliberately seek out and exploit account types that will attract the least scrutiny while maximizing laundering capacity.

Conclusions

The evidence from FinCEN SAR data and underground markets points to the same conclusion: bank accounts have become critical infrastructure for criminal networks engaged in fraud and money laundering. Rising SARs tied to wires, funnel accounts, and opaque sources of funds shows how deeply entrenched these schemes are within the financial system. At the same time, underground platforms reveal the mechanics behind this growth — fraudsters openly advertising aged or business accounts, promoting laundering “services,” and showcasing transaction histories to build trust. Together, these upstream and downstream signals reveal a professionalized ecosystem exploiting legitimate banking channels at scale .

Meeting this challenge requires a multi-layered policy response. For regulators, expanding transparency around FinCEN data (with privacy safeguards) could enable earlier pattern detection. Financial institutions should strengthen monitoring of funnel-account behavior, invest in behavioral analytics, and improve anomaly detection for wire transfers across geographies. Cross-institutional information sharing should be prioritized, enabling banks to identify and block suspicious transfers more quickly. Law enforcement should deepen cooperation with international partners, given the cross-border nature of many services.

Finally, consumers and businesses remain a key line of defense. Criminals increasingly seek access to legitimate accounts, offering payouts in exchange for use. Public awareness campaigns should warn about the risks of “account rental” schemes, while businesses must be vigilant about insider threats and compromised credentials. By combining better regulatory oversight, enhanced institutional defenses, and informed consumer behavior, the U.S. can begin to blunt the misuse of its banking system as a laundering tool.