Stanley Milgram’s notorious obedience experiment shocked the world—literally. In the 1960s, he asked participants to deliver what they believed were painful electric shocks to a stranger, simply because an authority figure instructed them to do so. Despite hearing screams and pleas to stop, most continued, revealing a disturbing truth: ordinary people can commit harmful acts when influenced by authority. An even more alarming fact is that people are unaware of how easily they outsource their accountability. Psychiatrists predicted that fewer than three percent of participants would administer the maximum shock level of 450 volts. In reality, 65 percent of participants went all the way to the highest voltage, even though they believed they were causing severe, and possibly lethal, pain.

Although the Milgram experiment was dramatic, there are everyday examples of outsourcing accountability, such as blaming others and systems—like rewards and compensation—for our choices. A landmark study conducted by Culture Partners in March 2025, involving 40,000 participants, revealed a “crisis of accountability, a crisis of epidemic proportions.” The results show that “84% of those surveyed cite the way leaders behave as the single most important factor influencing accountability,” yet 82% of those surveyed indicated that when holding others accountable, “they either try but fail or avoid it altogether.” Missing in the conversation is what it takes to be accountable, particularly when it comes to character. Simply put, the stronger our character, especially in terms of accountability, the more likely we are to exercise it effectively, and the less likely we are to outsource it unwittingly. First, we need to understand what accountability is, how it can appear in both deficient and excess vice states, how to develop it, and the systems that support or undermine it.

Defining Accountability

In Corey Crossan’s video introduction to the character dimension of accountability, she describes the Milgram experiment. Then she juxtaposes it with an everyday example from well known author, Brené Brown, who tells a story about blaming her husband after dropping her morning coffee. The blame happened in a nanosecond, as her mind quickly concocted a story about why he, not she, was accountable for dropping her morning coffee. A moment of reflection on when we blame others or claim something isn’t our fault is a good opportunity to examine the nature of accountability.

Although many people think accountability is straightforward — simply assign it, or you either have it or you don’t — the Culture Partners study results reveal an underlying problem. It starts with not understanding accountability. Corey Crossan describes: “Accountability is the willingness to own your actions and the outcomes that follow. It’s stepping forward when the stakes are high, taking responsibility when the path is unclear, and carrying the weight of your choices without shifting the burden to others. People with strong accountability don’t hide behind excuses, titles, or systems. They step up. They face consequences. They own the hard problems. And in doing so, they build trust—because others know they can be counted on when it matters most. They bring steadiness under pressure. Their presence sharpens focus, lifts responsibility across the team, and sets the standard for what ownership really looks like.” Becoming someone with strength in accountability also requires other character dimensions. My colleagues and I at the Ivey Business School built on research in philosophy and psychology to develop a character framework, in which accountability is one of the 11 dimensions. The behaviors associated with accountability are accepting consequences, conscientious, responsible, and taking ownership.

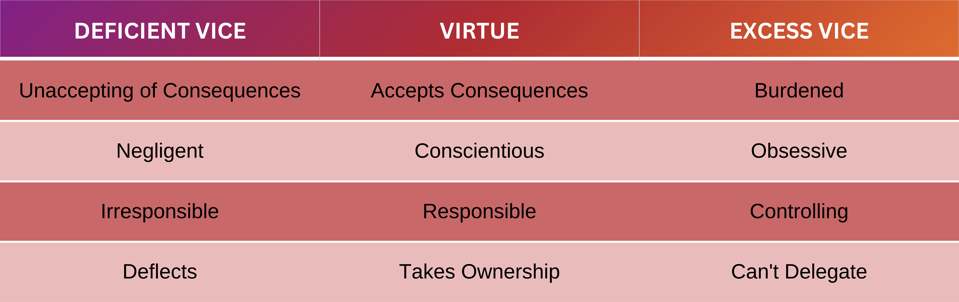

Not only can these behaviors be developed, but accountability can operate in both deficient and excess vice states, as shown in Table 1. The excess vice occurs when someone has strong accountability that is unsupported by the other character dimensions. Picture accountability as part of a wheel with judgment, or what Aristotle referred to as practical wisdom, in the middle. The other dimensions are transcendence, drive, collaboration, humanity, humility, integrity, temperance, justice, and courage. Someone who has strong accountability but low collaboration may find themselves taking on the weight of the world. Someone who lacks the optimistic, purposive, creative, and future-oriented behaviors associated with the dimension of transcendence may find they lack what I describe as the “renewable energy” that sustains them in sustaining their accountability even when the going gets tough. Instead of realizing the benefits of their strong accountability, they experience the excess vice state—being burdened, obsessive, controlling, and unable to delegate.

In my workshops with leaders, many find themselves in the excess vice state. Two things become clear to them. First, they grasp that their character profile influences others. Some people mirror the excess accountability, but often, leaders atrophy accountability in others. They begin to see why their subordinates seem to have the deficient vices of accountability – being unaccepting, negligent, irresponsible, and deflecting. Essentially, the failure to delegate and relinquish control sets up a vicious downward spiral that depletes accountability in others. This is the same dynamic of the helicopter parent. The excess vice of accountability in parents contributes to the deficient vice in their children. Second, and excellent news, is that leaders quickly grasp the need to strengthen their weaker character dimensions to support accountability better. One leader described that her strong accountability, unsupported by the patience and calm from the character dimension of temperance, likely contributed to her heart attack, which she described as self-induced. She described developing and strengthening her character as lifesaving for her.

Developing Accountability

My research with Corey Crossan outlines five stages of character development, each paired with a unique set of daily practices. The first stage involves discovering character by observing and recognizing how deficiencies, excesses, and virtues appear in ourselves and others. It’s easier to do this when observing others, but more difficult for ourselves because we tend to judge ourselves by our good intentions. In contrast, we judge others by their visible behaviors. Although we can notice when someone lacks accountability, understanding why is more challenging. For example, it is easy to see in Brené Brown’s example that she was deflecting blame on her husband, who wasn’t even in the room when she dropped her coffee. The harder part is understanding why she was quick to blame him. Often, weaknesses in accountability come from other character weaknesses, like humility and courage. As Brown explains, it takes courage and vulnerability (a behavior associated with humility) to be accountable. Humility is often overlooked in character development, yet it fuels learning, growth, and development. Behaviors like self-awareness, curiosity, reflection, and being a continuous learner help us see ourselves more clearly. In this first stage of character development, you can become a student of character, learning about yourself and others.

Level 2 in character development goes beyond just observing and identifying character; it focuses on priming and reinforcing character behaviors. This month, I have been focusing on developing the accountability behavior of “accepts consequences.” For the past week, I have gathered resources on a daily basis that help me activate becoming someone who accepts consequences. Building on level 1, I have observed the character of others and, using the exemplar strategy —one of the seven strategies for character development developed by scholars at Oxford and Wake Forest —I sought to gain a deeper understanding of Warren Buffett. A May 2025 article in Forbes by IESE Business School describes not only Buffett’s character but also how he embedded it in the organization – “At Berkshire, leadership and culture are rooted in accountability, transparency, and owner-like thinking. Buffett has spent decades developing complete managers, not temporary deputies. This is why Berkshire’s model outlasts flashier corporations. The numbers astonish (returns of a compounded 20% per year, vs 10% for the S&P 500), but the lesson is simpler: true leadership isn’t measured by tenure, but by building institutions where excellence becomes inevitable.” In addition to cultivating resources about exemplars of both strong and weak accountability, I have reflected on places, quotes, and images that can help activate my accountability. A classic approach is using music to activate character. In September 2025, I wrote about the character dimension of justice and described how the music from Les Misérables captivates me. It is not surprising that many songs also address accountability, particularly the acceptance of consequences. In the song “Who Am I?”, Jean Valjean wrestles with his identity and ultimately chooses to reveal himself, accepting the consequences to save an innocent man. The song underscores that accepting consequences comes at a cost, but failing to accept them erodes character. Not just the erosion of one’s accountability, but also other dimensions such as courage, justice, and integrity. The Virtuosity Character Spotify playlist offers songs for each character dimension, including accountability.

Level 3 goes beyond activating the behavior to strengthening it through daily practice. In the Virtuosity mobile app, I co-developed with Corey Crossan, we focus on the following themes for the four accountability behaviors. Strengthen your ability to accept consequences by facing the results of your actions. Strengthen your conscientious behavior by bringing diligence into everything you do. Strengthen your responsible behavior by honoring the people and roles that rely on you. Strengthen your ownership by shifting away from a tendency to deflect. For example, a daily exercise in accepting consequences is “Stand in the impact: Notice one way your actions today affected someone else. Acknowledge it directly, whether it brought help, harm, or extra work for them.” When I did this exercise, I noticed some small things that helped me strengthen my accountability. Often, when my husband asked what I wanted for dinner, which restaurant I preferred, or what type of bread I wanted at the grocery store, I would say, ‘It doesn’t matter.’ Although that was true, I had outsourced accountability for the decision to him and had failed to understand the consequences. In the grocery store, instead of choosing a specific type of bread, he would have to take the time to scan the shelf and guess what I wanted or didn’t want. Although this example may seem minor, it can escalate into larger issues in which people fail to take the time to understand or express their expectations and to consider the consequences, leaving others to figure it out and causing disappointment when expectations are not met. As the Culture Partners study revealed, “85% of survey participants indicated they weren’t even sure what their organizations are trying to achieve.”

The fourth level involves connecting the character dimension of accountability with other character dimensions. Developing accountability depends on other dimensions, not only to foster it but also to prevent it from becoming an excess vice. Often, people lose or have weak accountability because of deficiencies in other character areas. For example, strong collaboration, humanity, and humility, combined with low accountability, can lead to being a people pleaser and to following the crowd. Conversely, as Corey Crossan explains, “Collaboration can spread responsibility so no one person carries the full weight. Humility reminds us we’re not the only ones who can get the job done. Others can contribute in meaningful ways. And Integrity brings clarity, helping us distinguish which responsibilities are essential and which can bend—like juggling balls, knowing which ones are rubber and which ones are glass.”

The fifth level presents an opportunity to examine how accountability holds up in different contexts. This is where outsourcing accountability can easily happen. We haven’t anticipated the level 5 strength required. As Corey Crossan describes, “Accountability isn’t built in a single dramatic moment. It’s forged over time—in the steady, often invisible choices to own your actions, accept consequences, and step up when it would be easier to step back. Every time you carry responsibility willingly, or admit a mistake rather than deflecting it, you’re strengthening the anchor of accountability. But like any anchor, accountability needs balance. Too light, and you drift. Too heavy, and you sink. The risk isn’t just in too little—it’s in too much. And while noticing those patterns matters, awareness alone isn’t enough. To strengthen accountability, we need more than reflection. We need practice. We need structure.” The structure is not only the framework for daily practice to strengthen accountability, so we don’t outsource it, but also the structure associated with the systems in which we operate, which may lead us to outsource accountability. For example, AI could lead to outsourcing accountability. As I wrote in a January 2025 Forbes article, “Artificial Intelligence Needs Character-Based Judgment.” AI can make it easier for people to deflect responsibility by blaming decisions on algorithms or automated systems—“the AI said so” becomes a convenient excuse. As tasks become more automated, individuals may disengage from critical thinking, trusting outputs without questioning their ethical or practical implications. This shift risks eroding personal ownership over choices.

The word accountability is used so frequently that it has almost lost its meaning or has become taken for granted. Still, the accountability crisis is real. Understanding what accountability truly is, how it fits into the character framework, and how it can be cultivated are essential to tackling the crisis. It not only strengthens individual accountability, but alerts us to the contextual and systemic forces that undermine accountability. Being aware of those influences prompts us to take seriously the strength of character needed to buffet them, while also pointing to opportunities to influence them.