The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) increased the maximum CTC from $2,000 per child to $2,200 and indexed it for inflation going forward. In a departure from other recent changes, this change is permanent. That’s a positive step for many families.

But the OBBBA changes won’t reach the almost 1 in 3 children that live in families that get less than the full CTC because their parents earn too little. That’s because OBBBA did not change how the credit phases in— families must earn at least $2,500 to start qualifying for the piece of the credit that can exceed taxes owed, or the refundable portion.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

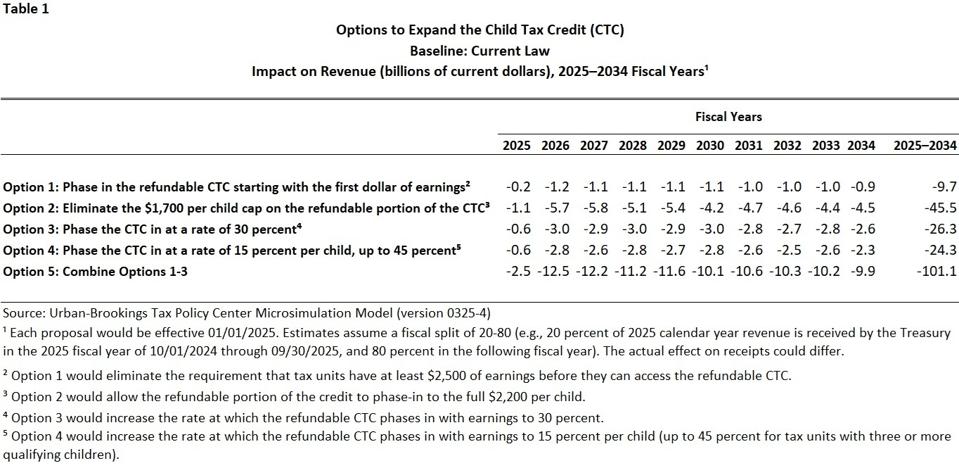

The Tax Policy Center modeled 5 options to increase the CTC. All continue to require that parents must have some earnings to receive the CTC and would deliver the vast majority of benefits to low- and middle-income families, the place where investments in children have the biggest impact.

Option 1. Phase in the refundable CTC starting with the first dollar of earnings.

Under current law, families with low incomes must earn $2,500 before they can begin getting the refundable CTC. This differs from the earned income tax credit, which begins delivering benefits starting with the first dollar of earnings.

This option would start phasing the CTC in with the first dollar of earnings. This would cost about $1 billion each year (Table 1) and would increase CTC benefits by about $100 on average for families in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, the bottom income quintile (Figure 1).

Option 2. Eliminate the $1,700 per child cap on the refundable portion of the CTC.

Under current law, if the CTC exceeds taxes owed, families can receive up to $1,700 of the balance as a refund.

This option would remove that limitation. It would cost about $5 billion each year. It would deliver an average of over $300 more per family for those in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, almost $200 on average to those with incomes in the second income quintile.

Option 3. Phase the CTC in at a rate of 30 percent.

The CTC currently phases in at a rate of 15 percent of a household’s earnings.

This option would double that, allowing the refundable portion of the credit to phase in faster. It would cost about $3 billion per year and would deliver about $200 more on average per family with children in the bottom income quintile.

Option 4. Phase the CTC in at a rate of 15 percent per child, up to 45 percent.

This option is a slight variation on option 3. The credit would phase in at a rate of 15 percent for families with one child, 30 percent for families with two children, and 45 percent for families with three or more children.

As a result, larger families with modest incomes could receive a bigger credit than smaller families with similar earnings, reflecting that larger families generally face higher costs. Like Option 3, this approach would cost about $3 billion each year and deliver roughly $200 more on average per family in the bottom income quintile.

Option 5. Combine options 1 – 3.

Combining the first three options would cost about $10 billion per year. This would deliver an average of $800 in additional benefits for families with children in the bottom income quintile and more than $200 on average for families in the second income quintile.

As my colleague Margot Crandall-Hollick explained recently, the rules governing how the credit phases in will have the most impact on the lowest-income families.

But the above analysis shows the phase-in can also affect families in the second income quintile who often do not qualify for the full CTC. Each of the options is highly targeted and builds on this year’s CTC changes, offering lawmakers ways to further expand the credit for working families.