Everyone talks about “the Dow”, as the Dow Jones Industrial Average is known. Yet who truly understands it? Created in 1896, the Dow remains the supposed barometer of zillions of business conversations around the world. It’s as if the 30 firms listed in it are taken to be unstoppable money machines. But what if the barometer itself fatally flawed?

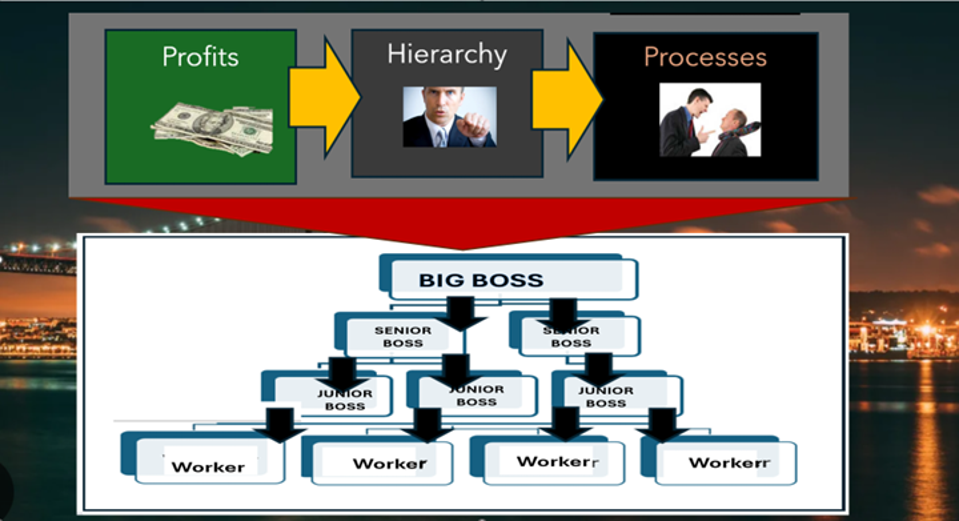

As my recent article showed in relentless detail, and as pictured above in Figure 1, we need to think again. Some firms in the Dow are value-destroying black holes; others are relentless value creators. The key to understanding the Dow? Understand the three most important value creation principles that both drive the biggest business winners and determine the inevitable losers:

- Customer value generally outperforms short-term profits

- Autonomous networks generally outperform hierarchies of authority

- Adaptive mindsets generally outperform mechanistic processes.

Note that when I say “outperform”, I am talking about long-term value–the relentless growth of value over many years–not the daily ups and downs of the stock market. Long-term value in the form of the 5-year or 10-year total returns reflects both sustained customer support for what the firm is doing and the sustained value that shareholders receive for their continued support of the firm. It also reflects how business contributes to society and our standard of living.

The Dow’s Price-Weighting Anomaly

The Dow has the anomaly that it is price-weighted, unlike other common indexes which use market capitalization. The pitfall of this approach is that a stock’s price—not the size of the company—determines its relative importance in the index. For example, in March 2025, Goldman Sachs represented the largest component of the index with a market capitalization of ~$167 billion. In contrast, Apple’s market capitalization was more than $3 trillion at the time, but it fell outside the top 10 components in the Dow.

The Dow’s Neglect Of Value Creation

Even more serious is the failure of the Dow to recognize that the basic principles of management have undergone a fundamental transformation as a result of first the Internet and now AI. Since the time of Frederick Taylor’s 1911 “principles of scientific management”, it was assumed that the purpose of a firm was to make money. To accomplish that, the firm needed to be run as a hierarchy in pursuit of profits, as shown in Figure 2. The result was a set of firms that performed adequately in the relatively stable economy of the 20th century.

Yet the fastest growing firms today are being managed very differently. The shift is being driven mainly by practitioners: average firms and business schools are still mostly catching up. In 2025, it’s time to follow Peter Drucker’s 1997 advice and “look out the window and see what’s visible—but not yet seen.” A paradigm shift in management has occurred. The new way of managing embodies three radically different principles, reflecting customer value, networks of competence and adaptive mindsets.

The data? Ruthless. The takeaway? Crystal clear: Master these three battle-tested value principles or watch your business disappear.

- Customer Obsession Trumps Profit Chasing: Prioritizing real value for buyers generally crushes short-term greed.

- Autonomous Networks Crush Hierarchies: Flat, flexible teams outmaneuver rigid command chains.

- Adaptive Mindsets Demolish Rigid Routines: Fluid thinking adapts to chaos; mechanical processes shatter.

These aren’t isolated hacks—they amplify each other like a chemical reaction. Nail all three? You have a chance to become a permanent value-creator. Botch them? You’re a relic like Boeing or 3M, hemorrhaging returns. Mixed bag? Expect mediocre muddling.

The ultimate irony: firms laser-focused on value creation make much more money than firms focused primarily on making money.

From Anecdotal Thinking To Evidence-Based Analysis

What’s equally important: the introduction of value-creation principles into the picture enables us to move from gossipy anecdotal thinking to something more significant. In article after article, book after book, and each new management fad, consultants and business professors alike latch on to some apparently attractive practice that occurred in one, or at most a couple of companies, and then proclaim the process to be worthy of emulation by all organizations. Much money can be made by the promoters of the new new gadget, even if it is just an old process with a new label. But the practice of creating value or running money-making companies does not advance.

It is only by examining systematically the evidence as to whether value is being created that management can become a serious and significant discipline. That’s what why principles of value creation are transforming everything we know about how the business world actually works.