I think I was wrong.

Last month, in discussing the AInxiety we are probably all feeling nowadays, I argued that our species had undergone two knowledge revolutions and was poised to undergo a third, with each revolution marked by a change in the exponential growth rate.

I still believe the main idea. The first revolution came with the first human, the first entity in the known universe capable of generating new explanatory knowledge. The second revolution involved writing, and the third revolution will still likely be AI. But I think I might have been wrong about two things: “writing” and the reason.

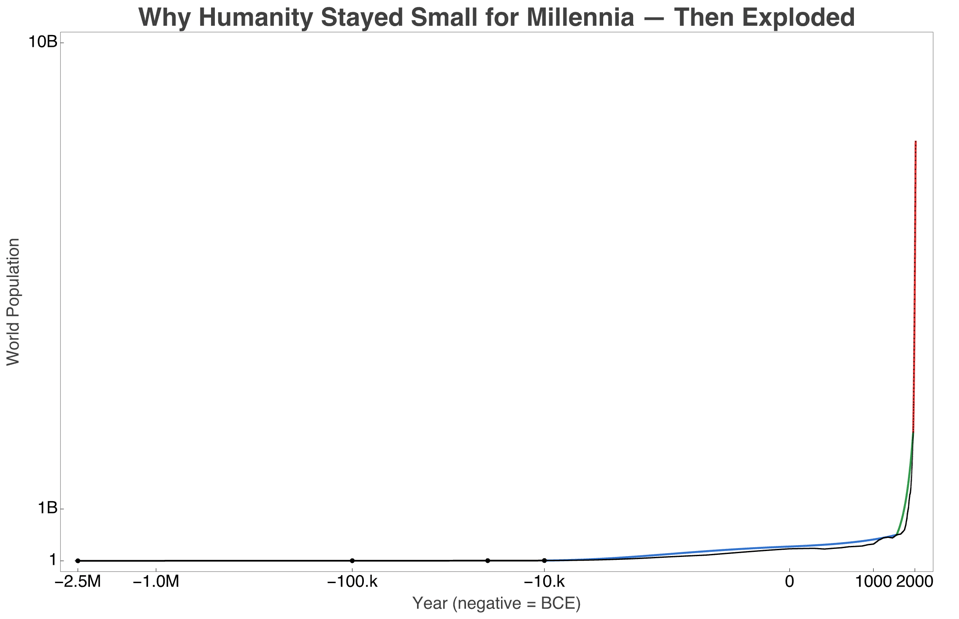

Data helped me find both errors. Here is a graph of the estimated world population from 2.5 million years ago to the present, with log axes everywhere. I continue to assume that knowledge is approximately proportional to population. The black dots show sparse ancient anchor global population estimates (e.g., Hassan 1981; McEvedy & Jones 1978; Biraben 1980) while the dense black line and dots after 10,000 BCE are reconstructed from the HYDE/OWID dataset.

My first error was in defining when “writing” occurred. We can see is that the big jump happened not 10k years ago when writing was invented, as I first assumed, but around 1500, just 500 years ago. What happened then?

The enlightenment and the printing press. It was indeed a form of “writing” that showed a substantive shift in the growth of knowledge. I had assumed it would have happened with the first scratches on clay, because it introduced a form of universality. But much like adding floppy drives to computers ostensibly also made their capabilities universal, it wasn’t until Usenet and bulletin board systems and the internet where the knowledge sharing ultimately took center stage.

My second error was my assumption that the growth rate was a single constant, with no volatility around it. A simplifying assumption, but, in retrospect, an oversimplification: it’s possible that the revolutions happened not because of changes to the average growth rate of knowledge, but to its risk.

I had assumed there was no risk at all, indeed that knowledge, like population, grows exponentially with a constant rate, or at least constant within its regime. But risk might be a far more interesting and satisfying explanation.

The blue, green, and red models in the figure above are calculated by assuming a single constant average growth rate, but allowing the volatility to vary between the three regimes.

From the first humans to the invention of writing, 2.5 Mya → 10k BCE:

μ = 0.55% / year, σ = 10.5%

From the invention of writing to the printing press, 10k BCE → 1500 CE:

μ = 0.55% / year, σ = 10.1%

From the printing press or enlightenment to now, 1500 CE → 2025 CE:

μ = 0.55% / year, σ = 1.0%

In other words, the invention of writing itself reduced risk a little bit, but the age of enlightenment reduced it ten-fold.

The determinants of knowledge growth, and the major revolutions that humanity has brought, may be better explained as reductions in risk rather than changes in averages. New ideas and new people appear at the rate of about half a percentage point per year. But sometimes ideas and people disappear, or appear much faster. The volatility used to be about ten percent, or twenty times the average growth rate. But after the printing press and the enlightenment, the volatility dropped to just twice the average growth rate.

Reducing risk can be a strong force for knowledge growth.

This is a general lesson. Knowledge sharing can reduce errors and that reduction in mistakes, both positive and negative, can make the overall growth explode.

What will happen as AI’s hopefully begin to aid or lead the charge in automated knowledge generation? There is not much further down for the volatility to go.

Here, the impetus may come from splitting risk into two components: the bad or downside risk, and the good or upside risk. Even if the downside risk remains unchanged at about one percent per year, if the upside risk returns to its ten percentage points level, this next knowledge revolution may be the last the universe will ever see. Knowledge can become not a rarity but a ubiquity.