The child tax credit (CTC)—the largest tax benefit supporting families with children— has swung through big changes in recent years. Generally, the pattern of expansion has been for the credit to be increased to a fixed level and then stagnate, which leads to rising costs eroding the value of the credit.

The 2025 reconciliation act, or the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), differed from these recent expansion efforts. It permanently increased the maximum credit amount to $2,200 per child and indexed it for inflation.

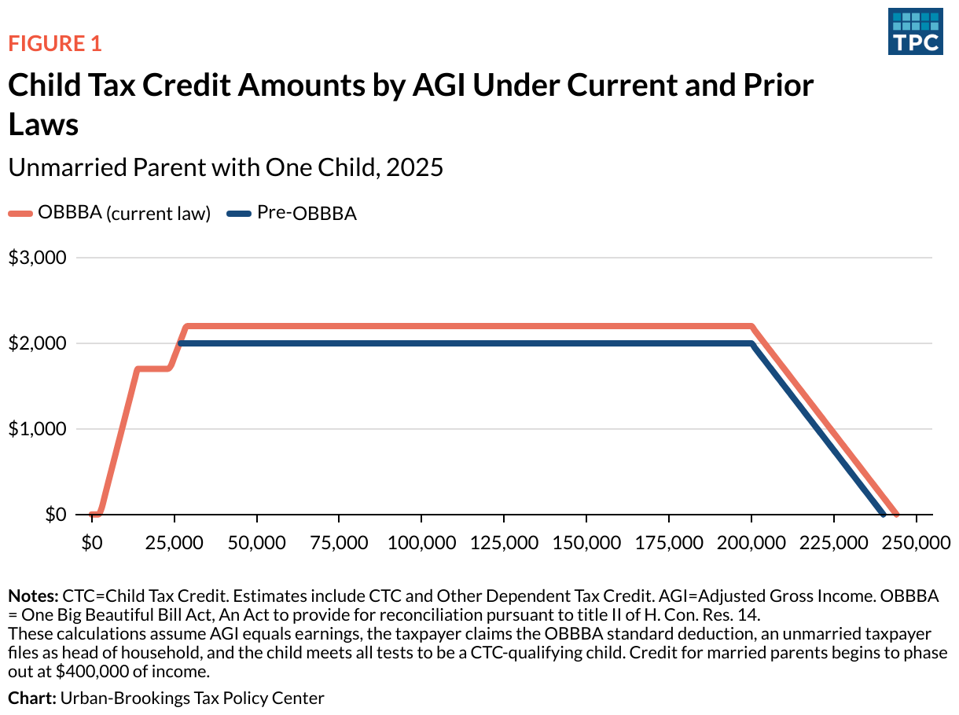

A permanent, bigger CTC is good news for many. OBBBA made the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s (TCJA’s) expansion of the CTC permanent, preventing the CTC from dropping from $2,000 to $1,000 per child (alongside other related changes to family tax provisions). And, more than that, the OBBBA increased the maximum credit to $2,200, which will now grow with inflation after 2025 (Figure 1). These changes help middle- and high-income families offset the taxes they owe.

These changes do little for families with low incomes, because the credit’s pre-OBBBA phase-in rules remain in place. And, as under prior law, that amount grows each year with inflation. But the amount of credit a family can receive beyond taxes owed is limited to 15 percent of earnings above $2,500. A larger credit with these same phase-in rules means that more children now live in families that cannot receive the full CTC because their parents do not earn enough. TPC estimates that number jumped from about 17 million to 19 million under the new law, about 30 percent of all children.

And there’s more bad news. Average benefits will decline slightly under the new law for the lowest-income families with children—largely because about 2 million additional children with Social Security numbers (SSNs) who cannot be claimed by someone with an SSN will now be ineligible (Figure 2). Rather than qualifying for the CTC, they can get—at most—a $500 credit that can only be used to offset taxes owed. Average benefits for middle-income and higher-income families with children will increase by about $200.

A basic principle of the CTC is that all else equal, larger families receive larger benefits. This is true for most higher-income families, but not low-income families. Because of the credit’s phase-in limitations, 1.1 million children in low-income families with multiple children will get the same credit as if their families had only 1 child under age 17. This could be changed by phasing the credit in faster for larger families who have modest earnings.

In all, the changes to the CTC were a mixed bag for families with children. A larger, permanent, inflation-indexed credit helps many families plan with greater certainty. But, despite research suggesting that investments in children with low incomes pay off more than many other social policies, millions of children in low-income families remain excluded, along with the economic returns that come from investing in them.