Depictions of violence against women in Western art history is a feature, not a glitch.

Murder, rape, abduction.

The Renaissance and Baroque periods, two centuries of artwork spanning roughly 1500 through 1700, are especially notorious. Artists and societies obsessed with Greek and Roman mythology and the Bible found violence against women everywhere they looked in those sources.

“The Rape of Europa” represents one of the most popular themes during the period. Popular among artists and celebrated among patrons. The celebration of these paintings has never ceased. Throughout museum collections around Europe and North America, Old Master paintings portraying the “Rape of Europa”–and other actions of violence against women–are on public display without so much as a shrug to the notion of how these artworks might marginalize or normalize the violence they show.

How can this be?

How is this ok?

Depictions of rape presented as if they were baskets of fruit in a still life. Nary a second thought.

“It’s such a part of the fabric of the history that we almost don’t see it, you almost have to come to it with fresh eyes somehow,” painter Jesse Mockrin (b. 1981) told Forbes.com. “I remember a ‘Rape of Europa’ picture at the National Gallery in (Washington) D.C., and the (wall) text said, ‘This lovely little picture…’ it’s so disconnected from the subject.”

Museum wall text for these artworks treats them like landscapes.

“Who is the artist? What time period does this represent? How is this historically significant,” Mockrin continues. “How does it fit into this long narrative that we’ve passed down, as opposed to, what is the story, and what does it say about patriarchy and our cultural inheritance, the world we’ve inherited from the past, and how different things are now, or how similar?”

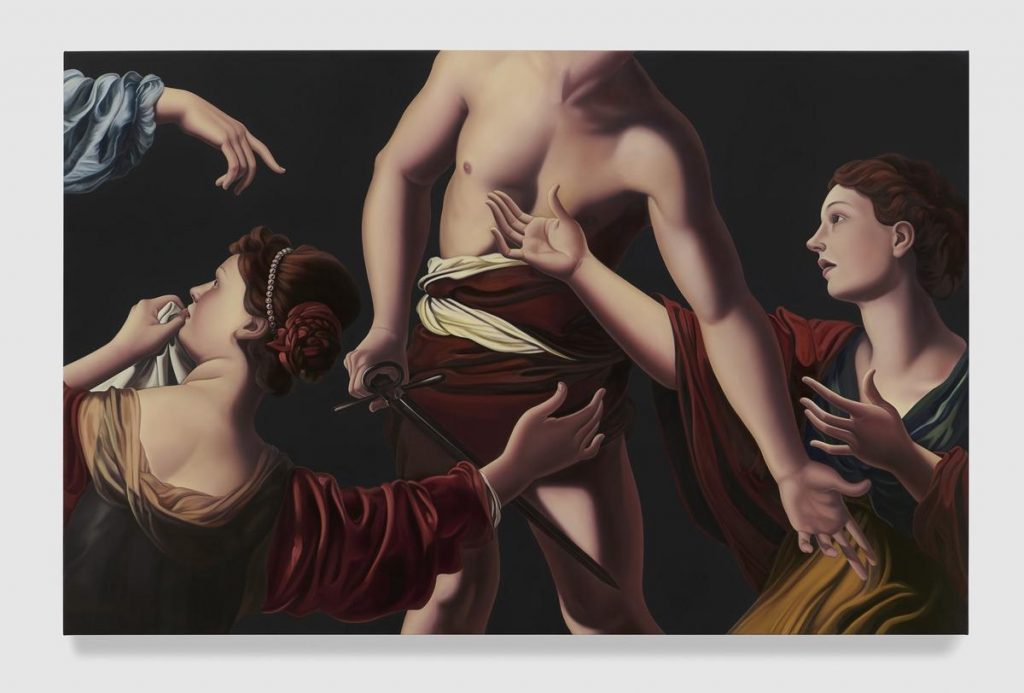

Mockrin calls out the casual indifference to violence against women in art history and modern museums while centering the women upon whom the violence was visited in her paintings. Paintings produced in the dramatic Baroque style she celebrates and critiques. Paintings on view September 10, 2025, through March 8, 2026, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

“There is so much laid on top of the female body in the history of art. The female body has to represent lust, the life cycle, painting itself, it represents sin, the sin of sexuality,” Mockrin explained in a YouTube video promoting the exhibition. “When we look at these art historical images in their context, we can be blind to the actual violence of the stories that they depict. I’m hoping in my works to make it more apparent and to draw attention back to patriarchal ideas that you can see present in this whole lineage of art.”

“Jesse Mockrin: Echo” features 25 paintings and eight drawings in dialogue with the AGO’s collection of Baroque era masterpieces. Mockrin radically re-envisions familiar historical subjects—Bathsheba, Solomon, and Daphne among them—through her own contemporary, feminist lens.

“Echo,” narrowly, refers to Echo, a nymph from Greek mythology forced to forever repeat that which has come before; Mockrin picks up the story in Only Sound Remains (2025), a large-scale oil on canvas. Broadley, “Echo” the exhibition, stems from the artist’s introduction to the AGO’s collection. In 2017, she came across images of the AGO’s Massacre of the Innocents (c.1610) by Peter Paul Rubens online. She reimagined the Biblically inspired painting as a cataclysmic cliff over which women were pushed into nothingness.

What’s Old Is New Again

Mockrin has a bachelor’s degree in art history. In graduate school, she became particularly interested in historical painting in an attempt to learn the techniques.

“In about 2016, I got more interested in the Baroque specifically because the Baroque has that high drama, high tension, and it felt like we were living in an era of high drama and high tension,” Mockrin explained.

The Baroque. Caravaggio, Rubens, Velasquez–that crowd.

Mockrin garnered wide attention for her Baroque-inspired artworks through a 2020 portrait of singer Billie Eilish rendered in the style of a Caravaggio painting for “Vogue” magazine.

“The Baroque, they have that way of presenting these same mythological and biblical stories that were illustrated in the Renaissance, but with more violence, more pulling, more action, more of that grand diagonal, the dramatic lighting; that tension, was interesting to me,” Mockrin said.

Also interesting to her were the women.

“These stories where women are really the catalyst for the action, they’re so rarely the subject of the story,” she continued.” It’s about how Lucretia is raped by the son of the king, kills herself, and then the Republic of Rome is founded in response. She is just the catalyst. It’s not a story about the violation of women or the intense shame of that cultural moment, of that kind of violence.”

Mockrin wasn’t raised in a religious household. An American, like most American kids, she had some small exposure to Greek and Roman mythology in grade school. The pervasive violence against women in the Bible and mythology was lost on her, however, until she began studying art history. Shocked, she did something about it.

“Story after story after story where women are featured and their violation is the catalyst to some major event, whether mythological or historical or biblical, (I’m) taking those stories and centering the female subjects so that we think about their experience anew,” Mockrin explained. “What it was like for them, and why were these stories so often painted, and how used we are to seeing them in museums and not really clocking just how violent or misogynist they are.”

Reimagining the fates of women.

Extracting details and scenes from historical paintings in the AGO’s Collection of European Art. Mockrin’s large-scale multipaneled paintings zoom and crop heroines, propelling their stories out of the past and into the present tense.

“By focusing in on details from these works, by liberating these figures from their original context, my hope is that I can empower the viewer to see these figures with empathy, and to see historical art anew,” Mockrin said.

Her figures are truncated and pushed over the edges of the frame, faces often obscured or composited. Backdropped against empty space, absent any signifying detail or decoration, Mockrin’s once historical figures and details exist only in the here and now. She paints in a style instantly recognizable as historic, but her approach to the subject–to women–is intensely contemporary.

A duality.

A contradiction.

“When you see the work, there is this feeling of, ‘Is this contemporary, or is this historical?’ That’s because of the technique,” Mockrin said. “There’s this dissonance that people feel when they look at it; they can tell it’s not truly historical, but that tension between the past and the present because of the style makes people question (the paintings) and wonder about how it came to be.”

Are the women contemporary or historic? Are contemporary women treated historically? What has changed? What hasn’t?

‘The Descent’

“Echo’s” centerpiece is Mockrin’s luminous, five-panel painting The Descent (2024). Stretching roughly 25-feet-across, the painting brings the crowded figures carved into a miniature ivory tankard produced in 1697 by Ignaz Elhafen to life size. Elhafen’s Abduction of the Sabine Women (1697) belongs to the Art Gallery of Ontario. Mockrin was struck by the action on the tankard when exploring the AGO’s collection.

She reveals the horrific truth of Elhafen’s delicate miniature embellishment by giving expression and presence to the nameless women of Sabine struggling to avoid abduction and rape by Roman soldiers. Mockrin does so using a technique known as grisaille, a technique popular during the Baroque. In grisaille, figures are fully modeled in the underpainting before adding color on top.

Mockrin references the tankard by painting the Sabine women in a color palette mimicking marble statuary or ivory carvings.

“I’m definitely not advocating for removing or burning art,” Mockrin said. “I am approaching this as a feminist with a critical lens, but also as a huge fan. This is the lineage of the art medium that I have embraced. These painters were extraordinary at their craft.”