The recent employment report revised net job creation substantially, leading many commentators to opine that the economy had weakened. An alternative view more accurately reflects the underlying data: Our labor force is hardly growing, so low job growth says little about the economy’s strength.

The employment market differs hugely from what it used be—and even more from popular perception as expressed in the news and by politicians. In truth, the U.S. labor force is hardly growing. Thus, jobs are not the best measure of economic performance. And both business leaders and government officials need to understand this new world.

In the Great Depression, layoffs were common and people correctly understood that the economy needed more jobs offered to the unemployed. That attitude eased a little when soldiers and sailors came home from World War II and found employment at salaries well above pre-war levels. But then the workforce grew rapidly. The baby boomers started coming of working age in the late 1960s and ‘70s. Then the children of the baby boomers started looking for jobs. And during this era, women increasingly entered the job market. In the decade starting in 1951, the U.S. labor force grew by 1.2% percent per year. Two decades later the growth rate more than doubled to 2.6% per year.

That era of labor abundance formed common opinion about the need to create more jobs. In public policy discussions, job creation dominated the topic. Local governments tried to bring jobs into their communities. National politicians promised to create more jobs. In businesses, managers knew they had plenty of applicants for every job. Catering to workers was a waste of effort.

The current decade, 2020 through 2030, has the lowest growth of the working-age population since the Civil War. And the percentage of females who choose to work has been roughly level since 2000.

Official estimates indicate the U.S. labor force shrunk by one-quarter of a percent from January through July 2025. Those are not high-fidelity numbers, but probably in the ballpark.

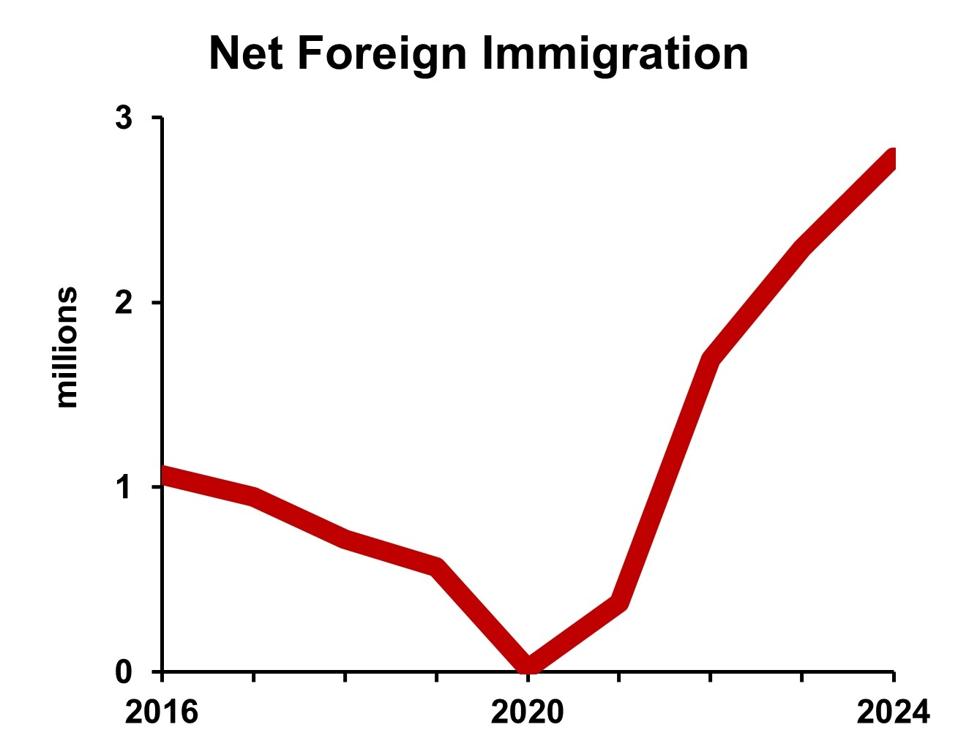

Foreign immigration plays a huge role in our low labor force growth. The data in the nearby chart incorporate estimates of undocu

mented/illegal immigration. Note the decline in immigration during the first Trump administration, 2017-2020, then the surge in immigration during the Biden years. Anyone can easily predict the direction for the second Trump administration.

Net immigration in 2024 (for the 12 months ending July 1, 2024) totaled 2.8 million people. About 2.1 million of them were in the 18-64 years age range. Without the immigrants, that age range would have shrunk by half a million people, because the baby boomers turning 65 exceeded the number of teens turning 18.

Now, mid-2025, immigration is very low at best and possibly zero or even negative, depending on the actual scale of deportations and voluntary departures. Our working-age population is probably shrinking.

With the pool of people available for work going down, job growth will be difficult. Wages would have to rise to induce more people to work. They would come from the ranks of college students, stay-at-home parents, early retirees and those otherwise not working. That is possible but requires stimulus at a level that would probably be inflationary.

In sum, President Trump’s immigration policy combines with the demographic trend of aging boomers to make job growth extremely difficult.

Business leaders face a number of issues that they must respond to promptly with respect to the labor force. They must acknowledge the tight labor supply in many different ways. When thinking of productivity, admonishing people to work harder won’t cut it. The people can walk across the street to find another job. Instead, business leaders must provide better tools, better training and better first-level management to boost output per worker.

Employee retention cannot be taken for granted in the new labor environment. In particular, the way managers could behave a generation ago won’t work today. It’s not so much social change and generational attitudes as that employees are hard to replace and will be for many years to come. Guides for better retention are readily available, but many managers are so caught up in current challenges that they don’t take time to learn how to better engage employees. High engagement correlates strongly with employee productivity and retention. Senior business leaders must ensure that first-level managers build their expertise in this area.

Employee recruiting needs substantial rethinking. Corey Harlock has pointed out that even small businesses need plans for attracting job applicants and then selling them on the job. That’s a huge reversal from the old approach in which the manager sifted through a large stack of applications and then the applicants nearly begged for the job.

On the public policy side, citizens should push back against political candidates who are so unaware of the facts that they push for simply more job creation. “Better jobs” must trump “more jobs.” Politicians should be challenged to look for impediments to opportunity and skill improvement. Occupational licensing, diploma requirements for government employment and poor performance of public schools and colleges must top the economic agenda for political candidates.

Our economy can continue to grow even if our workforce does not. Productivity improvement through upgraded skills and better technology will do the trick. But we need to understand that these are the key drivers for the future.