One of the defining features of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act (OBBBA) is its significant increase in the limit on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction from $10,000 to $40,000. This high-profile tax benefit for reducing taxable income is available for those who itemize deductions on their federal tax returns instead of using the standard deduction.

However, the higher cap on the SALT deduction comes with a catch: a phaseout for those with yearly income exceeding $500,000. While the income-tax rates for most of those taxpayers are 35% and 37% (the top two brackets), this phaseout of the SALT deduction can push your actual marginal tax rate to almost 46%. This significant jump has prompted financial advisors to suggest various strategies in response—including simply working less!

This article explains the tax oddity around the increased SALT deduction and the approaches to it that advisors are recommending.

SALT Deduction Review

State and local tax (SALT) is an itemized deduction on Schedule A of your Form 1040 tax return. SALT includes property tax and state income tax. In a state without an income tax, you can deduct sales tax.

You go with itemized deductions to reduce your taxable income when your itemized total (including mortgage interest and charitable donations) is greater than the standard deduction. Under the OBBBA, in 2025 the standard deduction is $15,750 for single filers and $31,500 for joint filers.

In 2018, the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) imposed a limit of $10,000 on the total SALT deduction available to itemize, no matter how much more SALT you actually paid. This was unpopular, especially in high-tax states such as California and New York. To get enough votes from Republicans to pass in the House of Representatives, the OBBBA needed to include a meaningful increase in the cap on the SALT deduction.

Accordingly, the OBBBA dramatically hiked the cap on SALT deductions to $40,000 per year from 2025 through 2029, with a 1% increase each year. The deduction limit is scheduled to return to $10,000 in 2030—expect to hear a lot about the “sunset” of this provision as that time approaches.

Alert: If you pay estimated taxes and are eligible for the higher SALT deduction, check with a tax professional (e.g. CPA, Enrolled Agent, tax lawyer) about any needed adjustments for the remaining quarterly payments of 2025.

How Increasing SALT Can Be Good

This is one tax-law change I personally benefit from. I live in a town in Massachusetts with high property taxes that pay for its excellent public schools and local government services. Additionally, the state income-tax rate is 5%. An extra 4% state tax applies to income of $1 million or more (not my worry).

The higher limit on the SALT deduction also makes up for my personal frustration with the OBBBA for permanently ending the tax-free employer reimbursement of up to $20 per month for bike commuting. That annoyed me because I bike to work year-round, including in the harsh New England winter, as part of my training for the Pan Massachusetts Challenge (PMC), a yearly fundraising event for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Higher SALT Cap Phases Down

As I explain in my recent Forbes.com article ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Affects Tax Planning For Stock Options And RSUs, phaseouts are the laser gun of the tax code. They vaporize taxpayer-favorable provisions to meet federal budget rules, while also adding complexity to the tax code.

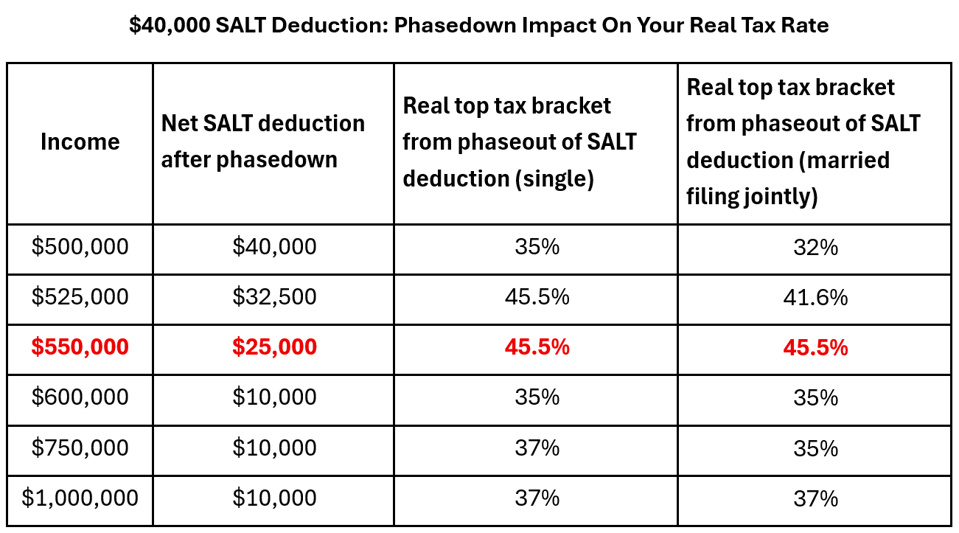

The OBBBA imposes a phaseout—called a “phasedown” in the tax law—on the new additional SALT deduction based on your income: from $40,000 down to the base $10,000 SALT deduction. For taxpayers with modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) above $500,000, the additional deduction phases out at 30% of every dollar over that threshold and completely phases out at $600,000 of MAGI. At that point, you are left with just the underlying $10,000 SALT deduction that is not part of the phasedown.

Because it takes away potential deductions from your taxable income, the phaseout increases your true marginal tax rate—how much in taxes you are really paying for each additional dollar in income.

Real Tax Rate Jumps In Phaseout Zone

Holistiplan, which provides a tax-planning platform with tools for advisors, calculated this tax increase for me. The 2025 numbers below are for both single taxpayers and joint filers, as the maximum SALT deduction and the income point where the phasedown starts are the same for both (a clear example of the “marriage penalty” in the tax code).

“The phasedown of the SALT deduction introduces a new ‘marginal’ bracket for those impacted,” observes Ben Birken, Vice President for Subscriber Support & Adoption at Holistiplan. “In fact, the tax code is packed with these non-published marginal brackets for things like the phaseout of the child tax credit, taxation of Social Security, when capital gains shift from being taxed at 0% to 15%, and the phaseout of the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction.”

In general, comments Birken, “you could say the tax code is a vast ocean littered with unseen tax torpedoes, of which the OBBBA adds even more.”

What Advisors Are Telling Clients

Financial and tax advisors are viewing the span of $500,000 to $600,000 in adjusted gross income (AGI), and the income range approaching it, as critical areas to watch for their clients.

The issue was concisely expressed by Jeff Levine, a tax advisor and the Chief Planning Officer with Focus Partners in St. Louis, Missouri, during a recent Kitces.com webinar on the OBBBA: “As you go from $500,000 of AGI to $600,000 of AGI, if you were getting your full $40,000 deduction for SALT taxes and you go down to $10,000, you’re effectively paying taxes on not $100,000 more of income but on $130,000 more: the $100,000 of income you actually received plus the $30,000 of deductions that you lost.” When you add in any state and local taxes to that income, he pointed out, you may end up keeping just half of the money you made.

Advisors recommend many planning ideas to try to hold your income below the phaseout zone. These include maximizing contributions to qualified retirement plans, such as a 401(k) or IRA; putting salary or bonuses into any nonqualified deferred compensation plan that’s available; exploring eligibility for other retirement or pension plans that defer income; and making bigger charitable donations (directly or to a DAF). Plus, where possible, you want to evaluate whether to avoid triggering more income, such as with Roth IRA conversions, nonqualified stock option exercises, and asset sales.

Levine urged advisors that “if your client is at $600,000 of income, you basically want to do anything you can, perhaps, to lower their AGI, because it’s that meaningful.”

He even (only half-jokingly) suggested to advisors that they may turn to some of their more workaholic clients and say: “You’re working your tail off, running around doing all your work, working all this overtime, or trying to max out your bonuses. Why don’t you just take it a little bit easier this year? Instead of making $600,000 you’ll make $500,000, but you’ll get back all this time in your life, and it’s only net-net going to cost you $50,000 after the taxes.”