I study fraud and cybercrime for a living. Then I became a case study.

I’ve spent years as part of the fraud-fighting community, publishing academic research, sharing insights almost daily on LinkedIn, and speaking at conferences around the country. While much of my work to educate and raise awareness has been embraced, not everyone is a fan. In 2022, after I publicly reported on the alarming rise of check fraud in the U.S. and spoke with several major media outlets, I became a target.

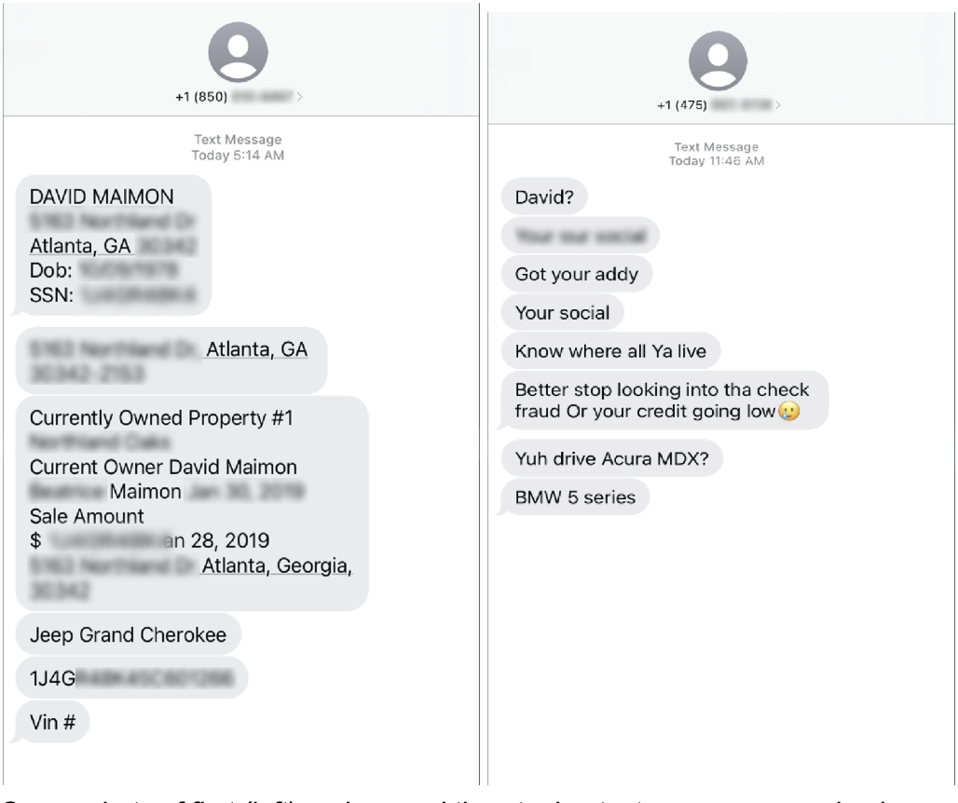

The first text message arrived around 7 a.m. I initially dismissed it. But the second message was far more explicit and wasn’t just a vague threat—it was personal. My full Social Security number, home address, and a direct warning: “got your addy, know where all y’all live. stop looking into the check fraud or your credit going low.

Concerned for my safety, my university immediately assigned a campus police officer to accompany me wherever I went. While this measure helped deflect any potential physical threats, something more insidious was already in motion. The same criminal actor who threatened me via text had posted my full identity—name, SSN, DOB, address, even my credit report—to one of the underground fraud forums my team had been monitoring.

While this exposure was deeply unsettling, it also presented a rare and valuable opportunity: for the first time, I could observe, up close and in real time, how quickly leaked identity data gets exploited by fraudsters.

Why it’s So Hard to Link Data Exposure to Fraud

Most leaked personal data, whether stolen from breaches, checks, phishing attacks or malware, circulates through opaque and decentralized criminal networks. The data is often sold or shared in encrypted Telegram groups, invite-only forums, or dark web marketplaces with no clear timestamps. Because of this, researchers rarely know when an identity was first listed for sale or accessed by bad actors. On the other end, when that identity is eventually used to commit fraud—say, to open a bank account or apply for credit—it might not be detected for weeks or even months, if at all.

Even if you know when an identity was leaked, matching it to a fraud attempt is nearly impossible. Institutions (financial firms, credit bureaus, government agencies, and public databases) operate in silos. There is no centralized system to link the moment of exposure to the moment of exploitation. Without visibility into the dark web and cross-platform monitoring, it’s nearly impossible to draw a clear, causal line between when an identity is posted for sale and when it’s exploited.

To complicate matters further, linking a fraud attempt to a specific leak often requires access to sensitive internal records—such as KYC data or transaction logs—that are protected by privacy laws and corporate policies. The result is a murky, delayed, and ethically constrained landscape, where timelines are incomplete and attribution is uncertain.

Unless the identity in question happens to be your own.

A Front-Row Seat to Fraud: The First 96 Hours

At exactly 9:56 a.m. on March 29, 2022 — minutes after receiving the second threatening message — my personal information was leaked to a Telegram fraud group: full name, address, SSN, date of birth, and even a PDF of my credit report.

I began searching online fraud markets to see if my information had been posted. I found it almost immediately. I alerted my identity theft protection provider, then sat and waited. Within a couple of days alerts started arriving. These alerts suggested that by March 30 — less than 24 hours after the leak of my identity — fraudsters had used my identity to attempt to open accounts at multiple financial institutions, as well as pull my credit report. Working with a victim specialist, we carefully reviewed the suspicious activity and flagged each questionable inquiry. In total, 10 alerts arrived within that first day.

I also requested my ChexSystems report to track any new bank accounts opened in my name (ChexSystems is a consumer reporting agency that tracks deposit accounts across U.S. financial institutions). When that report arrived, it showed six fraudulent accounts had been opened within four days of the leak.

One account in particular stood out: as if to make a point, the fraudsters had gone so far as to mail a debit card linked to one of the fraudulent accounts directly to my home address. The card bore my name and came with a phone number I was supposed to call to activate it.

After the Storm: Analyzing the Long Tail of Identity Exploitation

After that first month, things went quiet. The alerts stopped, and I assumed the worst was behind me. I was wrong.

Just a few weeks ago, a letter arrived from the Lifeline Support Center in New York. For context, Lifeline is a federal program that provides monthly subsidies for phone or internet services to low-income individuals. According to the letter, someone had used my identity to apply for these benefits, and I was now being asked to upload supporting documents to complete the application.

I had never applied for Lifeline. This was a clear signal: my stolen identity was still actively being used, this time to exploit a government assistance program.

Realizing I’d grown complacent, I decided to dig deeper—this time using more sophisticated tools and data sources to see what was happening in the background. With access to internal databases from SentiLink, a major identity verification and fraud detection company I work with, I searched for any records of identity theft attempts tied to my name and Social Security number. What I found was eye-opening.

In total, there were 5 incidents in March 2022, three in April, two in May, then one in August 2023, and another in April 2024.

Zooming out, several patterns in the fraudsters’ behavior began to emerge. First, most of the applications used freshly-created email addresses, likely spun up for the express purpose of the fraud, and cycled through different contact details. Across the board, there was a consistent rotation of emails, phone numbers, and physical addresses, likely designed to evade identity verification systems. Interestingly, while some fraudsters used burner phones or untraceable contact information, others left behind real, personally identifiable phone numbers — even as they were in the act of identity theft.

Second, the fraud attempts showed how broad and adaptive the strategy had become. My identity had been used to apply for everything from consumer loans and property leases to telecom services, federal benefits, and even a tax-related service.

Third, the volume of activity slowed over time. By mid-2022, the pace had noticeably dropped — perhaps due to increased monitoring, the flagging of my data in fraud databases, or simply the reuse value of the leaked information.

But in August 2023, a new and unusual application surfaced — one that included a traceable phone number. For the first time, I was able to link the fraud back to a specific individual. The applicant, who appears to live in New Jersey, has a lengthy criminal record, including charges for breaking and entering, assault, and battery.

Then, in April 2024, my identity was used yet again, this time in connection with a tax-related service. Specifically, an account was created under my name with a tax preparation service, followed by an attempt to fraudulently file my taxes. Unlike the earlier flurry of activity, this attempt was targeted and seasonal, aligned with tax season, and likely designed to take advantage of high-volume government processing windows.

One final and important note from my analysis: it does not appear that any organized fraud ring was behind the continued misuse of my identity. Instead, the pattern suggests individual actors — likely monitoring Telegram fraud channels — picked up my information and incorporated it into their own schemes. My data had become part of a wider fraud supply chain, passed from one bad actor to the next, each adapting it to their own criminal playbook.

What This Means for You

My experience underscores a sobering reality: once your identity is exposed, you’re not a one-time victim. You’re probably a long-term asset in a criminal system where your personal data can be recycled, traded, and exploited for years. The fraud may come in waves, or return over time in stealthier, more targeted forms.

If this happens to you, here’s what I learned the hard way:

- Move quickly. File police reports, freeze your credit, and start monitoring, not just the three main credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian and TransUnion) but also the ones like ChexSystems that track checking and savings accounts.

- Stay Vigilant. Just because the alerts stop doesn’t mean the fraud is over. It tends to linger, waiting for the next opportunity to surface.

- Use the right tools. Visibility matters. Strong identity monitoring tools can help you spot issues before they escalate.

- Track everything. I have the advantage of working in the fraud space, but anyone can watch for suspicious patterns — look at emails, phone numbers, account applications. Free tools and a little online sleuthing can go a long way.

The initial incident is rarely the end. It’s usually just the opening move. In this harsh reality, the most powerful protection isn’t just a freeze or a lock — it’s awareness and proactivity. Once your information is out there, you’re not just guarding against fraud — you’re managing an active threat that learns how to adapt. Staying on top of how your identity is being used isn’t paranoia, it’s a necessity.