History of Tariffs in America

The history of tariffs in America is a long one. In fact, tariffs have been a part of the American fabric since the early days of the Republic. The first tariff legislation was introduced by James Madison, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, and enacted in 1789. He argued for modest tariffs, understanding the destructiveness of excessive tariffs. In today’s world, excessive tariffs – or the threat of them, has changed the dynamics of international trade. In addition, America is in a much stronger position today than it was in the early days. How have tariff rates changed over the years? Are tariffs an obstacle to economic growth? Do tariffs cause inflation?

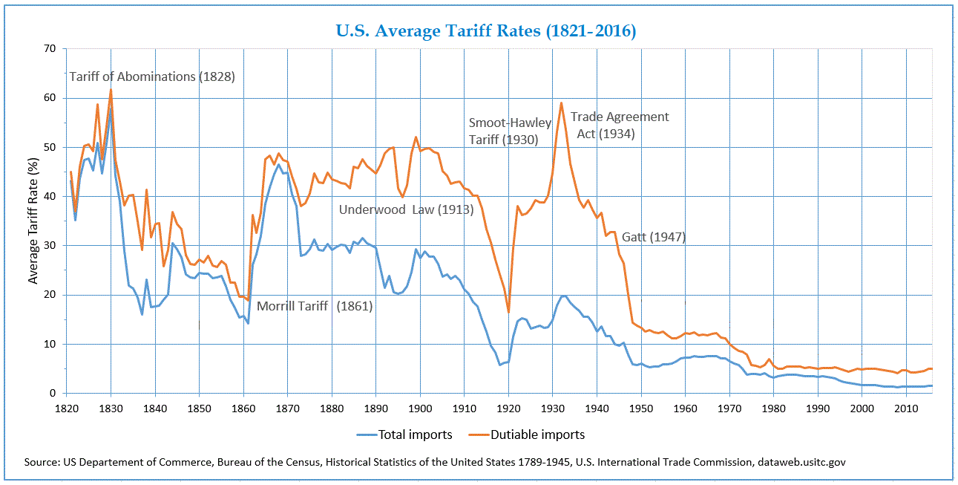

The following chart shows tariff rates on dutiable imports plus total imports from 1821 to 2016. Notice how they fluctuated significantly between 1821 and WWII before falling to historically low levels. On October 30, 1947, the U.S. signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947). This agreement was designed to promote international trade by reducing trade barriers such as tariffs. Thus, the stage was set for decades of open trade among nations.

The chart above lists six different pieces of tariff legislation. Not shown on the chart is the Tariff Act of 1789 signed by President George Washington and another round of tariffs after the War of 1812 to help pay war expenses. Just over 15 years later, Congress passed the “Tariff of 1828” signed by President John Quincy Adams. The 1828 act raised import tariffs to 60% and higher, which, at that time, was the highest tariff rate ever imposed by the U.S. This angered Southern cotton plantation owners who were very dependent on trade with Great Britain. Critics of the bill referred to it as the “Tariff of Abominations.” Why? Cotton plantation owners in the south were afraid that Britain would reduce agricultural purchases and retaliate with high tariffs. Not surprisingly, within two years of its passage, Great Britain was importing much less from the U.S., which angered the South even more.

Another round of tariffs occurred with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. This happened during the Great Depression as Congress was searching for a way to boost revenue and protect domestic businesses from cheap imports. The U.S. also had a trade surplus back then, which is not the best time to install tariffs. Tariffs are better suited when there is a trade deficit. Several economists believe the Smoot-Hawley Act made the depression worse and even prolonged it.

It’s interesting to note that prior to Smoot-Hawley, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1913 (Underwood Law). This act lowered the average tariff rate from 40 to 26 percent. The Revenue Act also created the modern income tax system with a one-percent tax on workers earning more than $3,000 per year, the equivalent of $94,909 in 2024. Most Americans made less than that. As tax rates rose, the income tax provided a greater source of revenue to the federal government and tariffs became less important. In essence, a higher income tax was a key reason tariff rates fell significantly following WWII and remained low until 2025. Enter Donald Trump.

Are Tariffs Good for the U.S.?

Again, President James Madison believed that modest tariff rates were acceptable since they are less likely to trigger a negative response from our trading partners. Apparently, the Trump administration doesn’t subscribe to Madison’s way of thinking. On April 2, 2025, President Trump announced massive reciprocal tariffs on imports from 25 trading partners. I should note that the EU is considered as one trading partner in that number. Days later he reduced tariffs to 10% on nearly all countries. Since then, tariff rates have vacillated quite a bit as negotiations with trading partners continued.

Three Types of Imports

According to a research paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco dated May 19, 2025, there are three broad categories of imports, which include consumption, intermediate, and investment. Consumption imports are final products that are imported and consumed by Americans. Intermediate imports are components of final products that are imported for production in America. Investment imports include equipment used in the production of final goods in the U.S.

Do Tariffs Cause Inflation?

Are tariffs inflationary? Not always. Why not? Because in the supply chain, the cost of tariffs may be absorbed at various points along the way. For example, the tariff on imports may be partially offset by the exporting company, the government where the exporting company is domiciled, or by the importing company. In each case, the end consumer would have to pay whatever tariff is left. Thus, if the entire tariff is allowed to fully flow to the consumer, then the customer will pay the bill.

Another reason tariffs may not cause inflation is based on finding a suitable replacement. If consumers can find an alternative to the import, inflation may not be triggered. However, if the replacement is much more expensive, it could cause a reduction in demand and a slowdown in the economy as consumers become increasingly careful with their spending.

We have just discussed a brief history of tariffs in America. Tariffs, which was a back burner issue, have now been placed at the center of today’s discussion. As early as the 1980s, long before he entered the world of politics, Trump was in favor of increasing U.S. tariff rates on imports. Today, during his second term as President, Trump is acting on his belief that U.S. trading partners have long been taking advantage of America. As the largest economy in the world by a wide margin, America is in a position of strength in that exporting nations need us more than we need them. Will Trumps strategy work? Will the result be a fairer system of trade with our partners? While no one can say for sure, we hope that all will end well.