Earlier this week, U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Doug Burgum announced a formal rescission of “18 obsolete or redundant Bureau of Land Management regulations.” The June 3 DOI statement announcing the recission called it “a decisive move to advance America’s energy independence and economic vitality.”

“This effort embodies our dedication to removing bureaucratic red tape that hinders American innovation and energy production,” said Interior Secretary Doug Burgum. “By rescinding these outdated regulations, we are not only reducing costs and streamlining processes but also reinforcing our commitment to energy independence and national prosperity — all while maintaining the highest standards of environmental stewardship.”

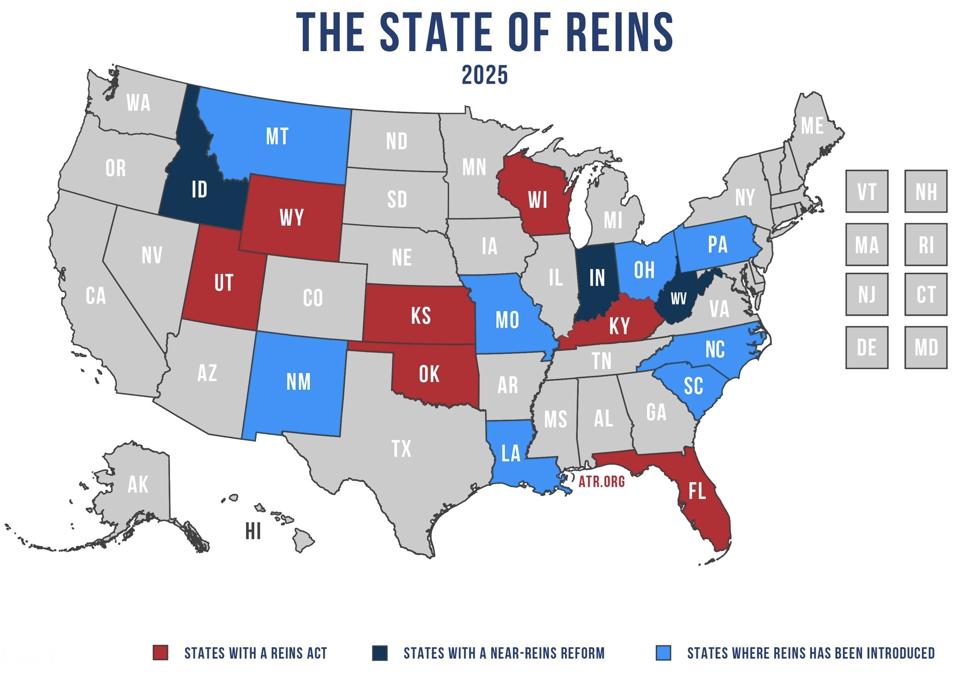

While the Trump administration continues to pursue reforms that reduce the federal regulatory burden, which now exceeds the combined cost of personal and corporate income taxes, governors and state lawmakers across the country are making progress this year when it comes to taming state regulatory burdens, namely by passing state-level versions of the REINS Act. The federal REINS Act, which would subject new regulations whose cost exceeds $100 million to congressional approval, is still awaiting consideration on Capitol Hill. In the meantime, the number of states with their own version of the REINS Act is continues to grow.

Eric Bott at Americans for Prosperity, which has been a driving force behind the nationwide expansion of the REINS Act, notes there has been a more than three-fold increase in the number of REINS Act states since Governor Scott Walker (R-Wisc.) signed legislation in 2017 making Wisconsin only the second state to have enacted this reform, with Florida being the first. Going into 2025 three states (Wisconsin, Kansas, and Florida) had a state-level REINS Act on the books, subjecting state regulations that exceed a specified cost to legislative approval. In three other states — Indiana, West Virginia, and Idaho — lawmakers had already approved reforms installing mechanisms similar to REINS, but with slight variations. New Hampshire has such a comparatively weak governor with so many checks in place, Bott explains, that the need for a REINS Act almost isn’t applicable in the Granite State.

“Florida has had REINS in the form of legislative rules ratification in place since 2010, and the process has earned the praise of regulators, legislators, and even the Florida Bar Journal,” notes Jon Sanders of the John Locke Foundation, a North Carolina-based think tank. “It causes regulators to work with legislators when they perceive the need for a costly regulation. This produces the coexistence between legislators and regulation that best serves people.”

Thus far in 2025, lawmakers in Kentucky, Wyoming, Utah, and Oklahoma have enacted REINS Act legislation. At least three more state legislatures are likely to pass a REINS Act this summer. REINS Act legislation introduced in Louisiana, Senate Bill 59, is now working its way toward Governor Jeff Landry’s (R) desk, with the Louisiana House passing SB 59 on June 2.

“Louisianans face multiple legal and regulatory barriers to starting and running a business,” said Daniel Erspamer, CEO of the Pelican Institute for Public Policy, a Louisiana-based think tank. “SB 59 by Senator Reese will empower legislative oversight committees to review, and approve or reject rules promulgated by agencies that will have a $200K per year or $1M impact over five years on regulated individuals or companies.”

On June 4, two days after the Louisiana House unanimously passed SB 59, the North Carolina Senate Regulatory Reform Committee held a hearing advancing HB 402, REINS Act legislation approved by the North Carolina House in April. The next stop for HB 402 is the Senate Rules Committee and then, supporters hope, the Senate floor.

As the REINS Act makes progress in North Carolina, opponents are speaking out. The Southern Environment Law Center, for example, testified against HB 402 during the North Carolina Senate Regulatory Reform Committee hearing this week, as did a representative for Democracy Out Loud, an organization that describes itself as a “peaceful activist community works together for a democracy that improves people’s lives.”

“We have regulatory agencies,” the Democracy Out Loud representative told lawmakers during the June 4 hearing. “You appoint people to the regulatory agencies. You have some control over major rules that come. You don’t need this law to take over.”

The irony of a pro-democracy group opposing a reform that would give democratically-elected officials final say on the costliest regulations, rather than unelected bureaucrats who are not accountable to voters, was not addressed during the June 4 hearing. It could, however, come up in the Rules Committee.

In addition to Louisiana and North Carolina, Ohio lawmakers are also on the cusp of passing REINS Act legislation. In a joint letter to Ohio legislators, a coalition of conservative organizations wrote that enactment of the REINS Act “will establish the necessary checks and balances by requiring legislative approval for new rules or regulations that impose a significant fiscal burden, ensuring that such decisions are made by elected representatives rather than unelected bureaucrats.”

If lawmakers in Ohio, North Carolina, and Louisiana enact the pending REINS Act bills in the coming weeks, as many expect, nearly a quarter of all states will have a REINS Act on the books going into 2026. What’s more, REINS Act legislation is primed for further expansion next year in South Carolina, Montana, Missouri, and a host of other states.

President Donald Trump has endorsed the federal REINS Act, the most recent version of which was introduced earlier this year by Congresswoman Kat Cammack (R-Fl.) and Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.). At the current pace, however, a sizable chunk of the country, maybe even most states, will have a state-level REINS Act by the time this reform is enacted federally.