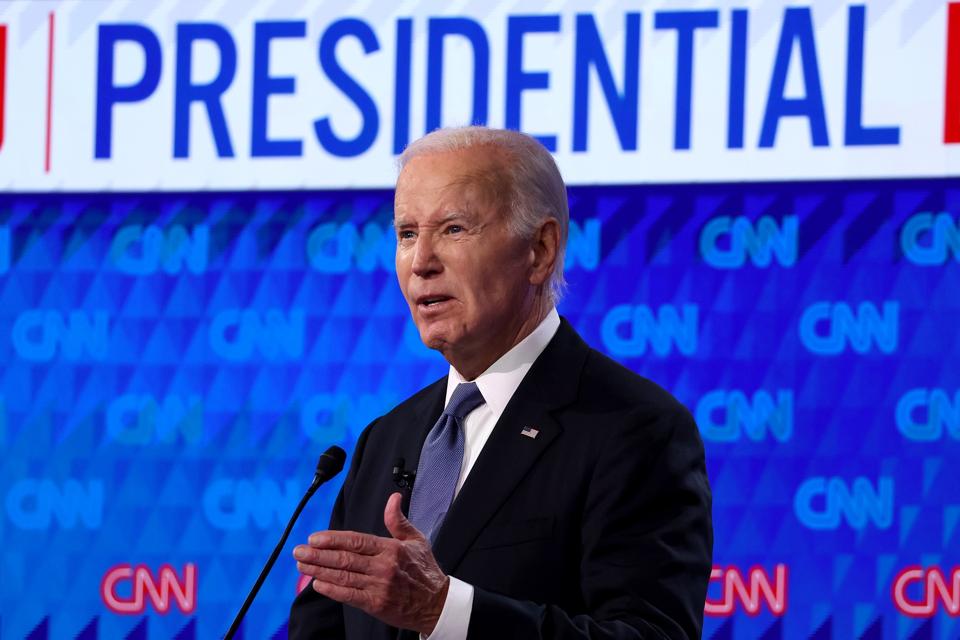

When and how should boards of directors prepare and respond to concerns and issues about the health of their CEOs? These governance-related questions could become top-of-mind for boards this week thanks to the headline-making revelations in “Original Sin.” The book, which will be published Tuesday, details how President Joe Biden’s aides and family members downplayed the impact of his health- and age-related issues during his presidency.

The failure of a board to act when it suspects or has evidence of the underlying health conditions of a CEO could create a crisis for the organization by affecting its activities, image and success. “That is why boards have to step in when a CEO’s health starts to compromise decision-making or firm performance. If a CEO is exhibiting signs of burnout, erratic behavior, or sound judgment, that is when the board has to step in,” Joosep Seitam, the co-founder and CEO of Icecartel, a men’s jewelry e-commerce platform.

It can be challenging and disheartening for boards to confront CEOs about issues related to their mental ability. “Addressing potential cognitive decline can be incredibly difficult—it’s a sensitive topic, much like approaching a loved one about similar concerns,” Danielle Sabrina, a crisis communication expert at Society22 PR told me in an email interview.

“However, very early-stage neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s can be subtle, especially in high-functioning individuals like CEOs, yet quietly begin to impact leadership, decision-making, and overall company stability long before a formal diagnosis. These symptoms often go unnoticed or are misattributed to stress, burnout, or personality shifts,” she warned.

A CEO’s Age Can Be A Touchy Subject

In some situations, the age of CEOs can be as much of a concern—and a touchy subject—as their health. “I’ve seen some aging CEOs demonstrate resistance to change, delay succession planning, and cling to legacy decision-making that no longer serves the business or market,” Sabrina observed.

An aging CEO can represent a slow and simmering crisis scenario that eventually catches board members by surprise. “Aging affects us all, but workplace and reputation implications can create unique challenges that develop gradually over time,” Sally Branson, director of Sally Branson Group, told me via email.

A corporate leader’s age does not have to automatically trigger a board’s concern. Consider 94-year-old Warren Buffet, the longtime leader of Berkshire Hathaway, who recently announced that he will retire at the end of this year. “Buffett announced the news at the end of a five-hour question and answer period without taking any questions about it. He said the only board members who knew this was coming were his two children, Howard and Susie Buffett,” according to the Associated Press.

Boards should not wait until the age of their leaders becomes a concern or problem. It’s always best —sooner rather than later—to establish and enforce policies and protocols that address the health and effectiveness of their corporate leaders. “Most organizations face legitimate questions about leadership capacity as CEOs age, creating clear and present repetitional vulnerabilities if they are not properly addressed….”, according to Branson.

Rationalizing A Board’s Inertia

Boards can be reluctant to discuss the age of their CEOs or plans to succeed them out fear of being labeled insensitive or discriminatory “I’ve worked with executives across industries and watched boards rationalize inertia in the name of respect. What gets buried under loyalty is often deep denial—about health, relevancy, and the unspoken toll of leading through era after era without pause or reflection,” Patrice Williams-Lindo, CEO of Career Nomad, observed in an email interview with me.

As CEOs and expectations about their performance change, boards should update their oversight of them accordingly. “We can’t all age like Rupert Murdoch and keep on keeping on well into our nineties—even if one could argue some of the key reputational issues his organization faces are now stemming from issues of a deeply personal nature, such as succession. We can not all demonstrate such longevity in leadership roles, these represent outliers rather than the norm, and boards should be governing for the most likely scenario,” Branson of Sally Branson Group pointed out.

To help prepare for those scenarios, Williams-Lindo suggests providing CEOs with “dignified ways to step back without feeling erased. Power doesn’t have to disappear; it can evolve into mentorship, chair roles, or strategic ambassadorship.” She also recommends making continuity plans part of the organization’s governance culture. The issue “isn’t just about old age. It’s about readiness—at any age. Whether it’s illness, controversy, or burnout, boards need real-time continuity plans.”

Just as important as dealing with these issues is having qualified people who are ready to fill unexpected leadership vacancies. As I reported four years ago, according to the 2021 Global Leadership Forecast, only 11% of surveyed organizations reported they have a “strong” or “very strong” leadership bench. The finding can be traced to a failure by companies to provide leadership development and transition training for newly hired and current executives, according to Development Dimensions International.

Companies and organizations should ensure that they have included in their crisis management plans provisions for health-related issues. And, because no one lives forever, businesses should also have succession plans in place—and practice responding to those issues when testing the effectiveness of their crisis management plans.