With the storm of anti-diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies unleashed by President Trump, and the subsequent retreat by federal agencies, companies, and universities, you might think DEI is finished as policy. But many states and cities—including Washington D.C., Chicago, and New York–remain committed to racial equity in their budgets and policies. They continue working through technical and administrative challenges while anticipating major conflicts with the Trump Administration.

What Is Racial Equity Budget Scoring?

As the Urban Institute notes in a 2022 report, “for nearly 50 years, Congress has created and frequently amended scoring processes that provide…fuller information about the potential consequences of legislative proposals and advance various policy priorities.” Many states and cities also have adopted scoring procedures to give governors, mayors, and legislators more information about the potential impact of proposed or existing policies.

At the federal level, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is legally required “to produce a cost estimate for nearly every (non-tax) bill approved by a full committee of the House of Representatives or the Senate.” The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) makes similar official scoring estimates for all revenue bills.

So racial equity budget scoring is not a radically new technique—rather, it draws on existing scoring practice, now seeking to assess proposed policies and programs on their racial impact. Most scoring work produces additional information for legislators and mayors; scoring policies on their own rarely require any concrete actions by government officials or legislators.

Some critics of racial equity scoring sometimes say it is simply too complicated to do accurately, and just leads to unnecessary complexity and delays in policy and legislation, or people taking unfair advantage of it. (Others go further, seeing the entire effort as discriminatory and calling for its elimination.)

The critique of too much complexity and delay recalls similar criticisms of industrial policy. Harvard economist Dani Rodrik once wrote:

Consider a set of policy interventions targeted on a loosely-defined set of market imperfections that are rarely observed directly, implemented by bureaucrats who have little capacity to identify where the imperfections are or how large they may be, and overseen by politicians who are prone to corruption and rent-seeking by powerful groups and lobbies.

Rodrik cleverly points out that such factors are not unique to industrial policy (and, I would add, to racial equity scoring). Instead, such problems plague policy domains “such as education, health, social, insurance, and macroeconomic stabilization.” But we don’t reject working on those issues because there are recognized complexities in getting them right.

Budget Scoring Is Normal Government Practice

Although racial equity budget scoring may seem controversial due to current divisions over DEI, it can be viewed as a logical and consistent expansion of budget scoring, a widespread practice in American government. Regular government practices already score budgets, legislation, and policies for their overall cost, revenue, and policy impacts, often for specific effects on particular groups of the population.

For example, the JCT estimates tax changes for their impact on households by income bracket. Other analysts have combined JCT estimates with other data to produce racial equity analyses of tax changes, as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities did for the 2017 Trump tax cuts. Detailed scoring work has also been done by the Social Security Administration, the Treasury Department, and other agencies.

There is no single inventory of racial equity scoring policies around the country.

In a 2022 report I co-authored with the Brookings Institution’s Xavier Briggs, we reviewed and analyzed racial equity scoring initiatives. Scoring and analysis were stimulated by the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and also by the COVID-19 pandemic, where both the impact of the disease and the public health responses to it differed significantly by race.

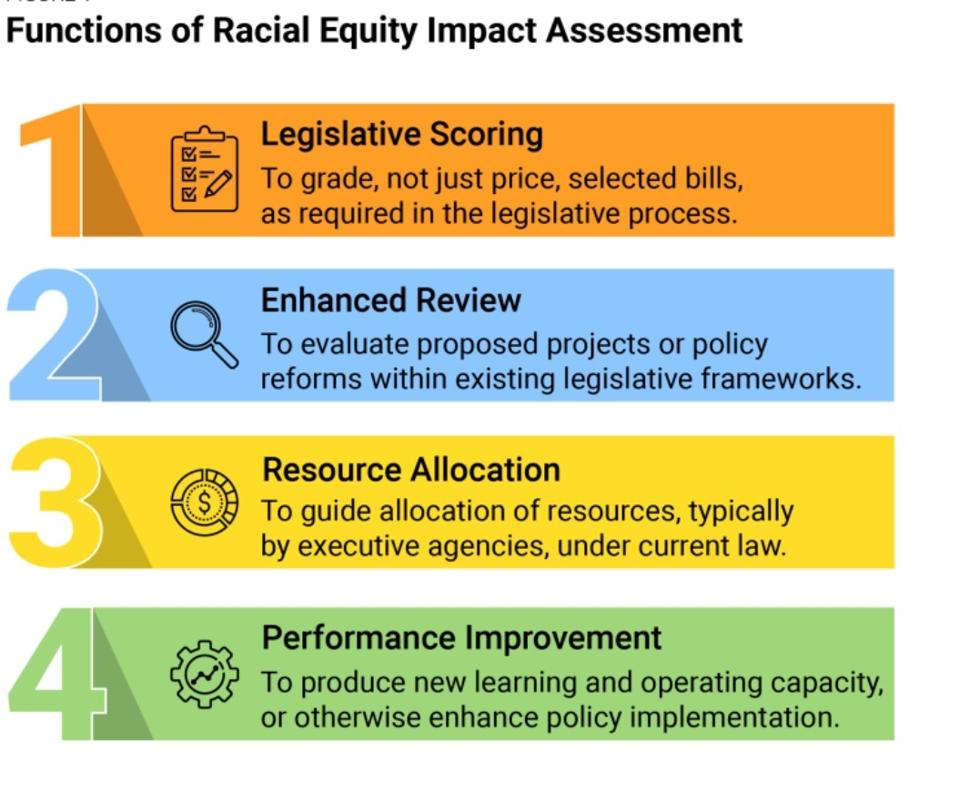

Briggs and I identified four functions of racial equity impact assessment:

—legislative scoring—grading, not just pricing, selected legislation;

—enhanced review—evaluating proposed projects and policies within existing legislative frameworks;

—resource allocation—guiding spending and resources from executive agencies; and,

—performance improvement—building learning and operating capacity, and helping policy implementation.

Racial equity analysis more often takes place for a specific topic, or within an agency or program. At least eight states have legislation requiring analysis for some aspect of criminal justice policy. And the Government Alliance for Race and Equity (GARE), which provides technical assistance and networking on racial equity, reports working with over 400 local, regional, and state governments.

The Trump Administration Pushes Back Against Racial Equity Policies

President Biden issued two executive orders requiring federal agencies to review their programs and policies on racial equity grounds, and develop agency practices, including appointing Chief Equity Officers and other steps. 23 agencies issued Equity Action Plans in 2024.

Of course, the Trump Administration has sharply reversed such actions by the federal government. They have issued executive orders against such planning and management, stopping spending and seeking to fire personnel working on racial equity, and prohibit the use of federal funds to universities, non-profits, and other organizations for DEI purposes. There is a tangle of lawsuits and cases against Trump’s actions, which are not yet fully resolved by the federal courts.

The political battle over scoring is just heating up. Many cities and some states carry out racial equity scoring on some or a broad range of their programs and policies. Others score selected legislation not only for budgetary impact, but for racial equity.

And some of those efforts are written into local law, or have even more legal forces. In 2022, voters amended the New York City charter—the governing document of the City—to require city racial equity plans. The charter amendments require the city to take a variety of administrative and policy actions in favor of racial equity.

What happens when such legal requirements at the state and local level meet the Trump Administration’s deep antipathy and use of federal policy to fight against DEI, especially where it is mandated by law? We don’t know how courts ultimately will rule on such conflicts.

But for now, some cities and states are still pursuing racial equity policies, improving on how they can be one, and developing data sources, analytic tools, and management practices to put them into place. Expect a large amount of bitter and deep political battles over these policies in the coming year.