It’s a testament to the lasting impact of Blade Runner that “like Blade Runner” has become all-purpose shorthand for describing virtually anything dystopian, neon-lit or cyberpunk — whether or not it truly resembles the world of Ridley Scott’s iconic 1982 film.

That the movie’s aesthetic has etched itself so deeply into our collective consciousness owes, in large part, to Syd Mead, the legendary concept artist and industrial designer who dreamed up the film’s decaying Los Angeles — a neo-noir visual cityscape that felt both distant and just within reach.

But long before Mead rendered the crumbling, rain-slicked world of Blade Runner and other famous sci-fi cinematic universes such as Tron and Aliens, he created immersive visions of the future that would go on to inspire generations of artists and designers.

A sweeping new exhibit in New York called “Future Pastime” steps back from Mead’s Hollywood years to trace the complete arc of the late artist’s six-decade career, which evolved from working in automotive design at Ford to creating futuristic concepts for Chrysler, General Electric, Phillips and Sony, among other corporations, and eventually answering cinema’s call.

“His work wasn’t just about aesthetics. It was about engineering optimism, crafting worlds where technology and humanity advanced together,” exhibit co-curator William Corman said in an interview.

“Future Pastime” — which opens March 27 and runs through May 21 — highlights a lesser-known side of Mead’s work that captures quiet moments of leisure, entertainment and beauty in apocryphal worlds. Visitors will be able to get close up with the rich and intricate details in 40 years of Mead’s gouache paintings, an experience that photographs of his work can’t possibly replicate. Mead died in 2019, at 86.

“What sets Mead apart is his ability to balance radical imagination with practical design logic,” Corman said. “His futures aren’t distant dreams. They feel like places we could eventually arrive at, as if they’re simply waiting for technology to catch up.”

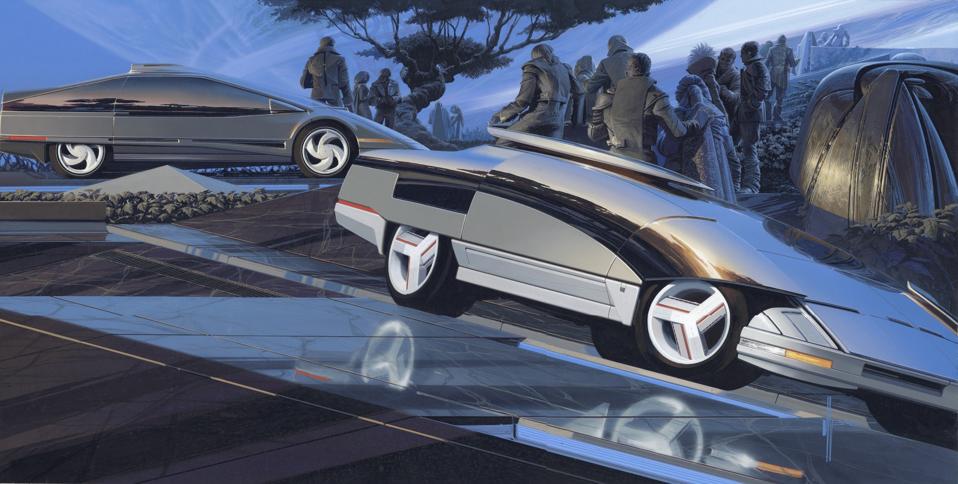

Picture boxy metallic vehicles a la the Tesla Cybertruck on an interstellar superhighway; giant racing robo-beasts; and a lavish retro-futuristic party where guests in sleek helmets and metallic garb lounge on furniture that looks like it’s crafted from recycled spaceships.

“These are not dystopias,” Corman said. “They’re nostalgic futures, familiar yet far off, where people still find time to drift, to gather, to dream. They remind us that Mead didn’t just design machines. He designed moments, capturing the emotional texture of the future.”

The artist, a 1959 graduate of the Art Center School in Los Angeles, often fused traditional methods with forward thinking. He cited Raphael’s mastery of scene setting and Caravaggio’s dramatic interplay of light and dark as influences on his own work.

“His use of classical technique to portray futures yet to be born was truly unprecedented,” exhibit co-curator Elon Solo said in an interview. “He was always showing us the future as if it were a world already known to us.”

What Shaped Syd Mead’s Sci-Fi Art?

Mead was born in 1933 in St. Paul, Minnesota and raised by a Baptist minister who moonlighted as an art instructor. He was, the curators say in a description of the exhibit, “a Midwesterner to his core — humble, honest, a small-town kid with a boundless mind.”

The Great Depression and World War II shaped Mead’s worldview as a child, and he spent his teenage years under the looming shadow of the Cold War and nuclear threat. These tectonic events not only impacted his belief system, but informed his creative direction.

“He believed that the bright future the world needed — in spite of the ‘insatiable consumption of its war machine,’ as he once said — could only come from careful planning and dreaming,” Solo said. “These works are the records of such dreams and aspirations for a future for us all to share, and as equals no less.”

In his enigmatic 1996 painting “Calvalcade to the Crimson Castle,” for example, humanoid figures mingle with alien-looking creatures amid metallic and organic structures.

Solo knew Mead personally and felt strongly about giving the public a chance to explore pieces like this one in person. “Future Pastime” runs at 534 W. 26th St., at the former Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery space in Chelsea.

“His work is masterful, emotional and bursting with complexity,” Solo said. “I don’t think there is a single major technologist, industrial designer, science fiction filmmaker, or innovator today that doesn’t credit Syd for at least a modicum of influence on how they got to where they are today.”