Weather modeling experts are being offered up to one million dollars a year in salary, Bloomberg reports. Hedge funds and commodity traders have led the charge to lure top weather quants to work. The broader implications of the data analysis trend apply across a wide range of disciplines.

Data analysis will continue to grow in importance across virtually all businesses. And if one company in a field is using good data analysis, the others must match that company or lose ground. Good data analysis seems to be expensive, it is being used because it has gotten cheaper. More data are available in digital format, so old-fashioned keypunching is not needed. Computers that can handle large batches of data are trivially cheap. The software has improved tremendously, relieving the analyst of most tedious programming. The result is companies that are more dialed in to demand for their products, more able to source the materials they need at the right time and in the right volume, and better able to adjust to changing conditions.

Matt Levine commented on the Bloomberg report, “I half-seriously argued recently that the attraction of quantitative finance might have ‘created conditions in which it is incredibly lucrative to get very good at statistical inference,’ and thus paved the way for modern artificial intelligence models.” He wondered if riches in finance help to incentivize young people studying fields such as physics or meteorology to get good at data analysis. Or maybe it’s a waste of talent for such bright people to work on commodity trading.

This approach to the connection between weather and commodity prices contrasts sharply with the old way, demonstrated by a hilarious anecdote from The Money Game by “Adam Smith” (a pseudonym for George Goodman), published in 1967. The narrator bought five cocoa futures contracts on advice from his friend The Great Winfield. When the price dropped, the narrator and the friend starting calling everyone who might know what was going on at Ghana’s cocoa plantations. Old contacts and friends of friends were questioned about the weather.

“Tell me sir, is it raining in your country now?”

“It always rains in August.”

Casual long-distance calls and telegrams were not working. “The Great Winfield decided we must send our man to West Africa to find out if it was raining and whether the Dreaded Black Pod Disease was spreading and whether indeed there was any cocoa crop at all.”

They dispatched a down-on-his-luck Brooklyn commodities trader who had never been to Africa before, who reported what he heard from other people staying at his hotel, and then got lost in the jungle.

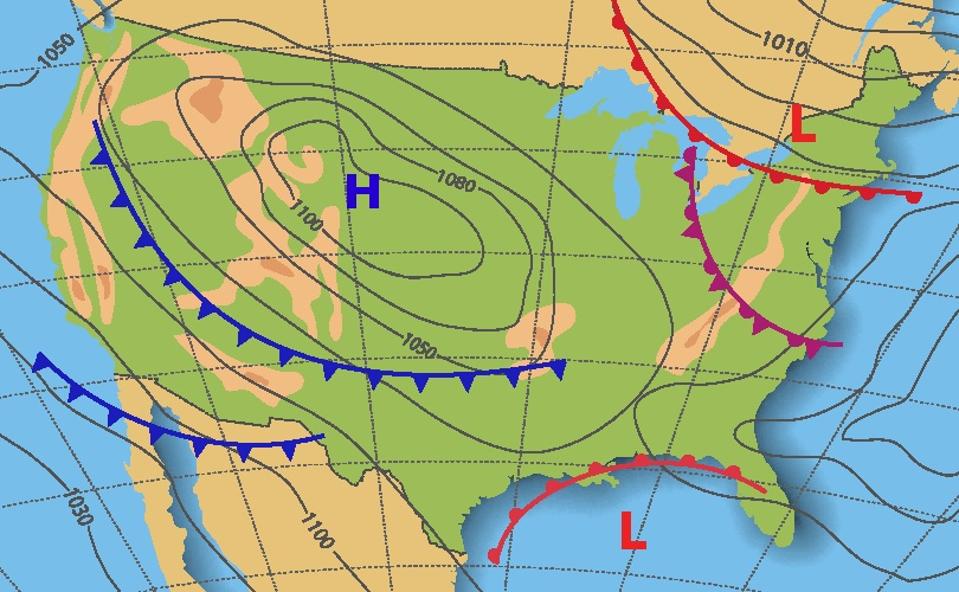

Today weather reports come from both on-the-ground meteorology stations and satellite reconnaissance. More data have led to better forecasts, including for local areas, as described by Chelsea Freas in an episode of the SailFaster podcast. (The episode is aimed at sailboat racers, but the weather forecasting discussion has broad applicability.)

These stories provide a great perspective: A forecast is not just a forecast; it’s a tool to make better decisions about a particular issue in a particular location. “Our man in Africa” didn’t really know what he was doing, but today’s data analysts have their game down.

Business leaders should spend some time wondering what they could do better if only some forecast were more accurate. After identifying a few key projections that could help the business, the data analysis effort begins by looking for analysts. Some may be available at the company already, or they can be hired or contracted for. Many people at the top of an organization don’t know all the information available both in their own computers and through publicly-available databases. And most certainly don’t know the techniques for of analyzing the data to create useful forecasts. But the top dogs don’t need to know the raw data or how to analyze it; just how to find some people who can. And a million dollars for a top analyst may be cheap relative to the value of the person’s work.