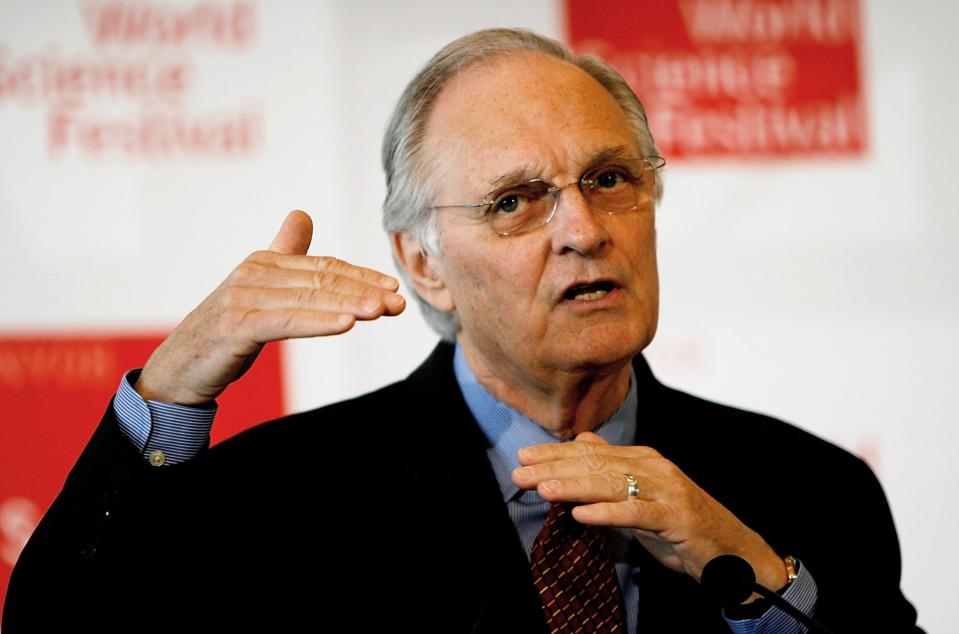

In Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of this interview series with Alan Alda, we covered a lot of ground, including the actor’s fascination with Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman and the Broadway play, Q.E.D., he made about Fenyman, fame, curiosity, fear, his podcast Clear+Vivid, the hit TV series M*A*S*H, Alda’s play about radium discoverer Madame Curie, Paul McCartney, and more.

Here, in Part 4, Alda tells us how as an actor he creates characters, discusses his ideas about influencial scientists of the 20th Century and the communicator Neil deGrasse Tyson, and more. Following are edited excerpts from a longer Zoom conversation.

Jim Clash: Your Alan Alda Center For Communicating Science at Stony Brook University helps scientists convey their technical knowledge in a way that the average person can understand it. You are a great actor, and you make it look easy. I’m sure it’s not. Explain to us non-actors how you do it.

Alan Alda: Last night, my wife and I were watching a TV series, and I said, “She’s really good, isn’t she?” My wife said, “Yes, she’s great.” I said she was so good that it didn’t look to be any effort, that she was really the person going through the experience. For my taste, good actors are like that. How they get there is different for different people. There are varying schools of thought regarding acting.

Some people believe that the way you understand the person to behave physically and vocally will convey the character to the audience. Others feel that you can express more without consciously making those efforts, but by working on your subconscious in a way that you’re not telling your face and body how to move. That way you get something more life-like. I’m more in this second camp. But there are wonderful, convincing actors who can put on a character like a cloak.

Paul Newman’s wife [Joanne Woodward] said that it takes 15 years to become a good actor, no matter what theory you work under, what training you do. I’ve seen people who showed no talent whatsoever, and, after 10 or 15 years of training, are able to do extraordinary things – moving, lifelike, inspired. You keep at it. I like to think each time I start a new project I’m inventing my method all over, trying to see what works best, experimenting.

Clash: If you were to make a list of the best science minds of the 20thCentury, who would you put on it?

Alda: I’m not so good at that. I find it hard to rank people’s talents and abilities. It’s not like a high-jump thing. The high jump is the same height for everybody. The person who figured out CASPEr [Cosmic Axion Spin Precession Experiment] is on a different scale than the person who figured out that there’s dark matter, dark energy.

Clash: Fair enough. How about a scientist that you think was influential?

Alda: The other night, I was with [Nobel Prize Laureate] Frank Wilczek, a pleasant guy. He invented a thing called the axion, which he says could possibly be what dark matter is, or closely related to it.

We were around a table of a dozen people and the question came up, “Is there a center to the universe or not?” The universe is expanding rapidly, in every direction. How come it’s hard for most to picture there not being a center to it? It’s the kind of question that demonstrates the difference between the way scientists are able to think, and the way the rest of us think.

Scientists can think mathematically, go over the edge of what we consider regular, everyday reality, and know something just as surely as if they could see it in reality, but by virtue of mathematics. But those higher mathematics are not readily available to most of us. So something like whether the universe has a center, and that it started from a big bang, is hard for most of us to picture, even be able to say it in words, because it seems so contradictory.

Let’s go back to [Richard] Feynman for a second. He said if you can’t explain it to a child, you may not understand it yourself. That really puts a burden on the explainer [laughs].

Clash: I’ve always thought of Neil deGrasse Tyson as a person who is able to take complex science subjects and make them understandable to us average Joes.

Alda: One of the things I admire about Neil that he does deliberately is keep track of what’s happening in popular culture. He knows what a great number of people in the culture are already aware of, and uses that as a doorway to explain more complex ideas in science. I think that’s a good idea. I don’t do it, I don’t keep that close a track on popular culture. I have to have somebody explain it before I know about it.