In the first two parts of this interview series with Alan Alda, we covered the actor’s fascination with Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman – including the Broadway play Alda made about the physicist in 2001, “Q.E.D.” – Dr. Edward Teller, fame, curiosity, fear and more.

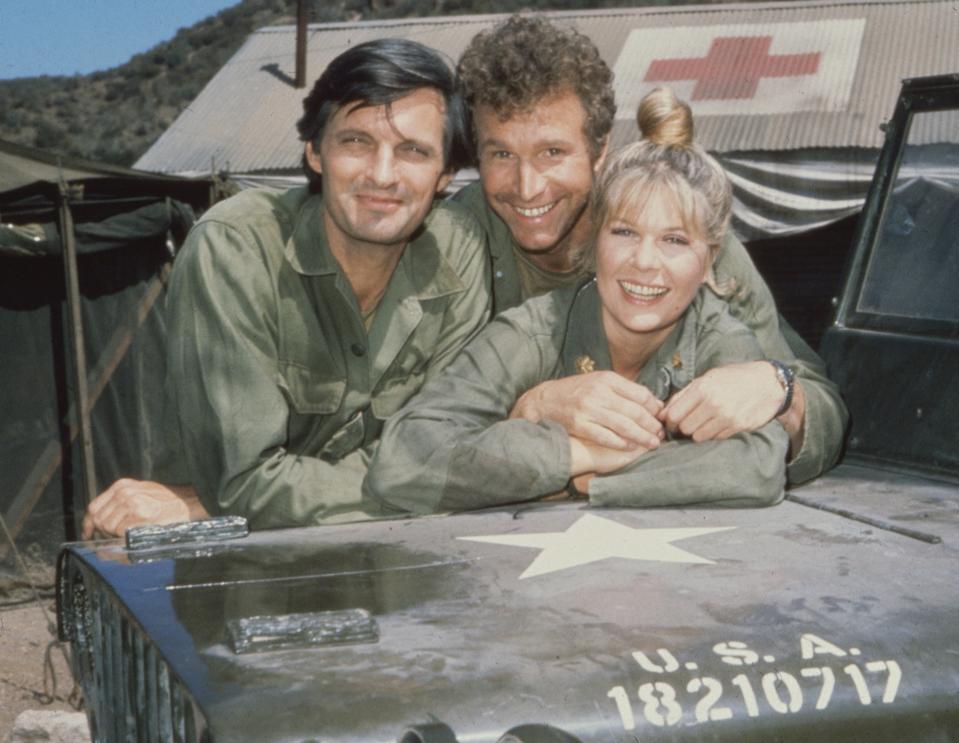

Here, in Part 3, we discuss Alda’s hit TV series M*A*S*H, his play about the discoverer of the element radium, Madame Curie, some of the more interesting guests he’s had on his podcast Clear+Vivid, including Paul McCartney, and more. Following are edited excerpts from a longer Zoom conversation.

Jim Clash: We have to touch upon your participation the TV series, M*A*S*H. What did you like best about doing the show?

Alan Alda: The most fun was learning to get better at what we all did. I got better as an actor, writer and director. It was thrilling to make those movements forward. There are few things more pleasurable than doing what you know how to do well. The only thing better is learning how to do it better.

Clash: Any favorite episodes that come to mind?

Alda: There are a number of them, usually ones where the story was told in an unconventional way. One in particular I enjoyed was one I wrote about the dreams of the people in the compound, the unit. But they weren’t just casual dreams, mostly the nightmares they were having. I thought it was an effective episode. Turns out later on the Internet I found out it was some people’s favorite and some people’s most hated show, because it wasn’t that funny, I guess. I don’t know.

I thought we had a deal with the audience that we could tell stories in an unconventional way, sometimes maybe not all that funny. But the next week we’d come back with more of what they expected. So we worked in many different styles, and that was part of the joy of making the show. I haven’t watched it much since we did it, though.

Clash: You also produced “Radiance: The Passion Of Marie Curie.” Why do a play about the discover of the element, Radium?

Alda: One thing I was interested in was that women in science never have had an easy time. There have been studies where the same resume had been submitted for work at a lab, both identical except that one had a women’s name on it, the other a man’s. When questioned, lab directors would say that the women was not as interested in science as the man. That interested me about Curie.

But also the story she lived was very dramatic. She suffered from being a woman in a time where women were not expected to be able to work the way men did. She was very depressed after her husband died in an accident involving a horse and carriage. She was comforted by another scientist. Eventually they had an affair as he was unhappily married. When that was revealed, around the time of her second Nobel Prize, the people in Sweden told her not to come pick up the prize because of the scandal.

The first time she won it, the committee only wanted to nominate her husband, Pierre, because the two had worked together. It figured because he was the man, he had really done the work. But he said that they had to give her half of the credit or he wouldn’t accept the Prize. When they got there, he was told that he would give the acceptance speech, not her. It was unfair.

Clash: Let’s discuss your current podcast, Clear+Vivid, a bit.

Alda: Because I like science, I’m interested in how scientists communicate. I try to make each show a model of communicating. If I don’t get it, don’t understand it, I keep after the guest until I do. The hope is that at least some of the podcast listeners will be on that same hunt for understanding, get somewhere they hadn’t been before.

It’s not only scientists, by the way. They are only a small part of who I have on. I talked to a guy who used to be a skinhead and realized one time when he was beating up a Jew, he was actually hurting a real person, and decided not to do it anymore. He spends his time helping other skinheads get out of that movement now. Another guest was one of the chief hostage negotiators with the FBI. So a lot of different kinds of communicators – actors, musicians, politicians. Sometimes the link to communicating is not so clear at first.

Clash: How do you choose guests?

Alda: There are three of us – executive producer, Graham Chedd, associate producer Sarah Chase, and me. Publishers send us requests because a book is coming out, or maybe we see an interview with someone interesting on YouTube. It’s importand that those people not only have an interesting thing to talk about, but can also come to life, that they can actually make contact with the audience.

A lot of it is about what you and I are doing right now. You can either bring someone out, or turn them off. Sometimes people with good intent wanting to bring out somebody just flatten their voice because they don’t express a genuine interest in the guest. I don’t mean to flatter you, but from the word go, you connected with me, made it much easier for me to talk to you.

Clash: Who is one of the most interesting guests you’ve had on so far?

Alda: I had a really good time with Paul McCartney. When he came into the studio, everyone was so excited. There was a piano in the room, and three guitars leaning up against the wall under a spotlight. So when he comes in, has asks me “What’s all that?” I told I had nothing to do with it. We were excited you were coming, so the staff put it out to get you in the mood.

As soon as Paul and I started our conversation, we did some vocal exercises together, just kidding around. Four of five minutes in, I said, “You’ve got the most memorable melodies in the world. How do you come up with them, find them?” He says, “Oh, I just play some oobly chords on the piano.” So I asked him what an oobly chord was. He says, “You’ve got a piano over there, I’ll show you what I mean.” So going from “what’s that” to playing a piano and looking for melodies was great fun. He’s really a good guy.