Neanderthals. Egyptian mummies. King Richard the III. Science continues to bring historic faces to view in extraordinary detail. The latest: an influential 6th century emperor whose DNA has yielded insights into his appearance, health and ancestry.

Emperor Wu, born Yuwen Yong, ruled the Northern Zhou dynasty in China from 560 to 578, during which time he built a strong military and unified the northern part of the country after defeating the Northern Qi imperial dynasty.

In 1996, archaeologists excavated Emperor Wu’s scattered bones and nearly intact skull from a mausoleum in northwestern China. Years later, using the contours of that skull and DNA extracted from a limb, researchers from China have created a modern-day portrait of him. In a new study published in the journal Current Biology, they detail their findings and methods, including how they verified the reliability of the DNA (the variable quality of archaic genetic material can pose significant challenges to forensic scientists).

“I find such facial reconstructions very interesting, since while I am interested in great currents of history, I am also interested in the particular people who moved within those great currents,” Professor Scott Pearce, a Western Washington University expert in Chinese history who was not involved with the study, said in an email interview.

The research team spent about six years studying the DNA, which contained information on physical traits such as hair and skin color. They combined that data with additional physical details suggested by a statistical model that predicts visible human traits using 41 genetic variations.

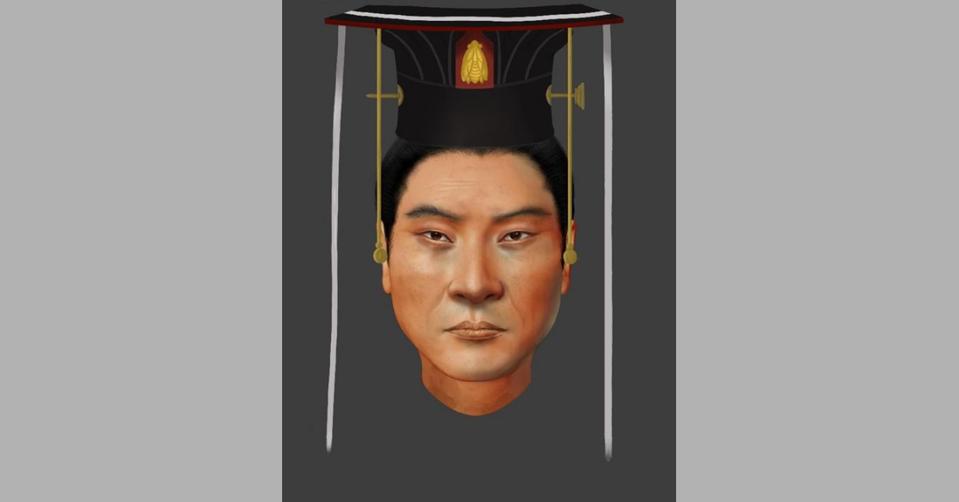

Using facial reconstruction software, they were then able to add those characteristics to a digital representation of the skull to produce a 3D portrait that further enriches the historical record of the emperor, allowing anthropologists and history buffs to see a photorealistic image that goes beyond centuries-old artistic portraits.

The digital reconstruction shows a heart-shaped face, brown eyes, black hair and intermediate to dark skin and high cheekbones. Emperor Wu was ethnically Xianbei, an ancient nomadic group that lived in what is currently Mongolia and northeastern China and played an active role in the country’s history for at least 7 centuries. The analysis showed Emperor Wu “had typical East or Northeast Asian facial characteristics,” according to a statement.

“Previously, people had to rely on historical records or murals to picture what ancient people looked like,” said study co-author Pianpian Wei of Fudan University’s Institute of Archaeological Science.

While we’ll never know for sure precisely what Emperor Wu’s face looked like, skulls are the most relevant discriminating elements for reconstructing faces, according to Philippe Charlier, a French forensic anthropologist at the Université Paris-Saclay who has extensively studied historical remains, including Adolf Hitler’s teeth. Craniofacial reconstructions resulting from skulls are reliable and efficient, he said.

DNA can offer complementary details on appearance, but “these elements are purely statistical, and are in no way certain, at least not definitive,” Charlier, who was not involved with the study out of China, said in an email interview. Still, he added that facial reconstructions have advanced in the last decade and now are “very reliable, provided that a computer engineer, an anthropologist and a paleopathologist are involved in the creation process.”

More Than Skin Deep

The DNA extracted from Emperor Wu’s bones goes beyond appearance, however, to offer potential clues into why he died suddenly at 36. Some archaeologists say the ruler died from illness, others say he was poisoned by rivals.

The researchers behind the new study found 698 single-nucleotide mutations in total, 42 related to pathogenic variants such as an increased susceptibility to gout, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and stroke. The team says further study with higher sequencing depth is needed to confirm this.

Nonetheless, while the team can’t say for sure how Emperor Wu died, they posit a stroke may have been at least partially responsible. That conclusion corresponds with written accounts of the emperor suffering from aphasia, drooping eyelids and an irregular gait.

All in all, the study offers yet another example of ancient-DNA analysis opening an intriguing window into the past. “I very much support DNA research,” Pearce said. “It’s a very important development in multiple ways, including the study of history.”