In 2019, the Starfish Institute, a non-profit advisory group I founded, conducted research for a Fortune 50 company on the challenges to recruiting and retaining front-line health workers in South Africa. Among all the reasons identified, one stood out: Nurses and midwives were undervalued as a profession. In some languages, “midwife” was a derogatory term. Lurking beneath the prestige challenge, interviewees explained, was the gendered nature of the profession, in which 70% of the workforce was female. The care-taking that front-line health workers did was seen as women’s work; it was undervalued and less prestigious; and, as a result, salaries were lower.

I had to travel halfway around the world to understand something that was happening to teachers in my own backyard: Women’s work is systematically undervalued and underpaid across every sector of our economy. Teachers’ persistently stagnant pay, usually treated as a technocratic problem of public finance or teachers unions, was, at its root, a cultural problem. Teaching, which is 75% female, has become coded as women’s work. Though teachers might be special in myriad ways, in this way, they are just like every other domain in which women predominate: underpaid. To change teacher salaries, we need to change how we value women’s work.

A massive study looking at U.S. census data from 1950-2000 found that “the proportion of females in an occupation affects pay, owing to devaluation of work done by women.” A new study by the University of Zurich found that men are twice as likely to leave fields that are “feminizing.” In a gendered version of the phenomenon dubbed white flight, as women enter fields that have been male-dominated, men leave, and the jobs they’ve left behind begin paying less, controlling for education, work experience, and skills. In case we think it has to do with the complexity of the job, the hours worked, or the degrees required (all arguments for teachers’ lower salaries), an analysis of medical specialties found that when female doctors begin to predominate in previously male-led specialties, it is associated with a “relative decline in earnings for physicians in these specialties over time.”

Teaching wasn’t always seen as women’s work, and when it happens in colleges and universities, where men predominate, it still isn’t. Catherine Connors, author of The Feminine Revolution, told me that “it was long believed that women were unsuited to teaching, because they weren’t as ‘rational’ as men. Once it became a norm for girls to be educated, education became more associated with childcare, and so with feminine-coded work, which is less valued. The less education looks like care, as in high school and post-secondary education, the more likely there are to be men, and the higher the salaries are.”

Paula England, a sociology professor at New York University, told The Upshot that when women start doing a job, “It just doesn’t look like it’s as important to the bottom line or requires as much skill.” Marianne Cooper, a Stanford sociologist, explains why: “There’s a reluctance to value things deemed to be intrinsic. So if women are just ‘naturally nurturing and good with children,’ then why pay them for it?”

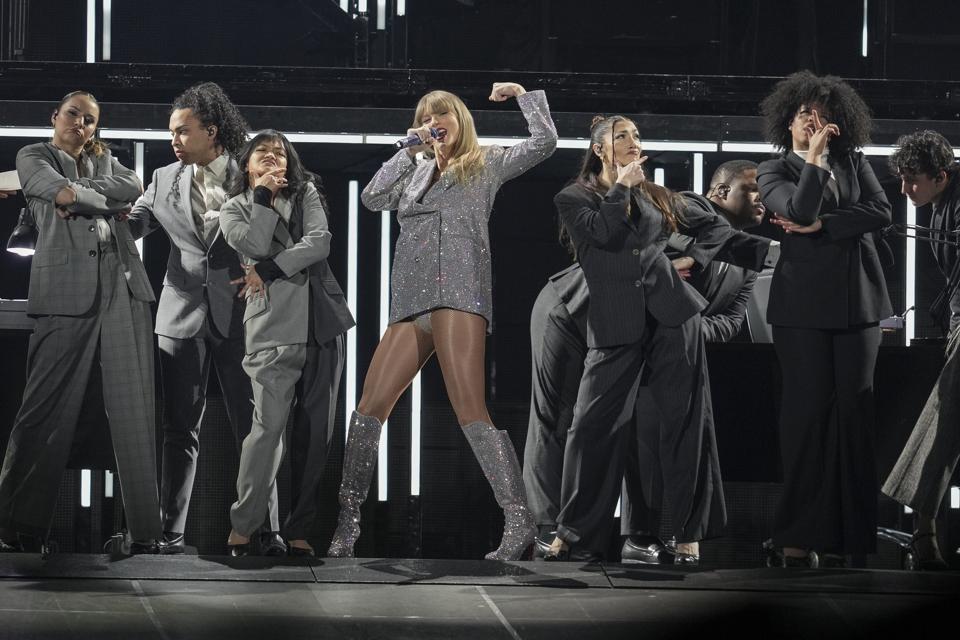

On the flip side, “we also see a lot of skepticism and outrage when women and their work cost top dollar,” says Rachel Sklar, longtime expert on gender equality and founder of women’s professional networks TheLi.st (disclosure: I’m a member) and Inner Circle. “There’s certainly been a lot of chatter about how expensive a ticket to Taylor Swift’s Eras tour is,” she continued, “but no one blinks at the price of a Super Bowl ticket.”

Eve Rodsky, author of Fair Play and founder of the Fair Play Institute (whose careforce I am on) believes that an unspoken message about women’s time is at the root: “What I found so pervasive all over my interviews,” she writes, “was the view that men’s time is finite and a woman’s time is infinite.” Women’s time is like air, and men’s time is like diamonds. Because women have infinite time, it doesn’t need to be valued like men’s. Rodsky’s on a quest to value all time equally.

Basic rules of supply and demand predict that a sector faced with shortages will increase wages to attract more people to the vacant jobs. The persistence of low teacher salaries in the face of longstanding shortages is puzzling until you apply the lens of gendered occupations and the resulting wage suppression.

Despite recent growth in teacher salaries in response to crisis-level teacher shortages, teachers still earn 24% less than comparable college graduates, with salaries that have barely budged since the 1990s. While real median earnings for full-time workers increased by 2.6% from 2010 to 2019, median earnings for teachers declined by 4.4% for high school teachers and 8.4% for elementary and middle school teachers.

The impact on the teaching profession is profound. Despite a slight uptick since 2019, enrollment in teacher preparation programs is down 20-30% over the past decade. Twice since 2016, Beyond100K, the nonprofit I founded, queried more than 500 people about why. The first time, the gendered nature of the profession barely registered. But more recently, when we asked the same question again, the perception that teaching, especially at the elementary level, is women’s work, “which tends to be undervalued and underpaid in our society”, showed up as among the highest-leverage of more than 80 unique challenges.

“The field of teaching has become devalued and feminized. Thus it is seen as less prestigious and salaries are lower,” one interviewee shared. Another said, “Teaching is a low-paying field, whereas other STEM careers are often high paying, because we consider education to be ‘women’s work’ and in the public sector, whereas other STEM careers are coded ‘“masculine’ and in the private sector.” Dr. Angela Jackson, professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, concurred: When you layer working in the public sector on top of the gender dynamic,” she explained, it’s no surprise that these regulated wages are stagnant.”

Yet raising teacher salaries could be the surest-fire way of improving learning and life outcomes for children. Barbara Biasi, a labor economist at Yale University, has found that increasing teacher salaries accelerates student learning, retains teachers, reduces student dropouts, and even narrows the achievement gap, leading some to advocate for the six-digit teacher salary. Biasi and other scholars question whether taxpayers would be willing to foot the bill, though they don’t attribute that reticence to gender.

To successfully change teacher salaries, we will need to change how we value women’s work. I can see the outlines of a powerful alliance of women — and men — working in women-led fields like nursing, teaching, social work, and certain medical fields coming together to advocate for a fundamental realignment of how we value women’s time and work.

Amanda Casner, an engineering major who decided to become a teacher, faced unrelenting pressure to reconsider: “At first, I was beyond excited,” she said, but at a Society of Women Engineers meeting, a colleague questioned her choice by describing teaching disparagingly as “stereotypically feminine.” A classmate said to her, “‘oh… but you’re so smart. Why would you settle for teaching?’” She began to question her choice and lie about her career aspirations.

It was a summer teaching fellowship that turned things around for her. “The experience was exhausting. Each day, we had to plan and rehearse lessons, teach three classes and an elective, co-lead a homeroom, manage behavior, connect with students during mealtimes, and meet with a coach for a feedback meeting. Managing all these tasks and more while keeping a positive attitude every day was exponentially harder than any engineering class I’d taken. It was also the happiest I’d been through all of college.” Now several years later, Amanda is a math and science teacher in Denver. “I finally began to understand that teaching is not ‘settling’; it requires huge amounts of ambition and skill. Teachers’ effects on our country’s future citizens,” she knows, “makes us some of the most important people in the workforce.”

Amen.

On this International Women’s Day, whose priority is “Invest in women,” let’s flip the script and double down on changing how we value the time women (and men) spend doing the essential work of unlocking the potential of every other person on the planet.