We live in times of high uncertainty. That fact prompted the Drucker Forum, just ten days ago, to announce a five year initiative to re-frame the very concept of management. In implementing the initiative, the Drucker Forum could learn much from what the military itself, in both the U.S. and Europe, has learnt about managing in the quintessential context of high uncertainty—the battlefield.

Tackling the wicked problem of managing forces on the battlefield involves a recognition that warfare is probabilistic and unpredictable, with large elements of disorder and uncertainty. Some parts of the military have learned to cope by a combination of decentralization, spontaneity, informality, loose rein, self-discipline and initiative. This can result in acceptable decisions made faster. The approach requires the involvement of all echelons, with communications characterized by interaction, both vertical and horizontal, rather than one-way and top-down.

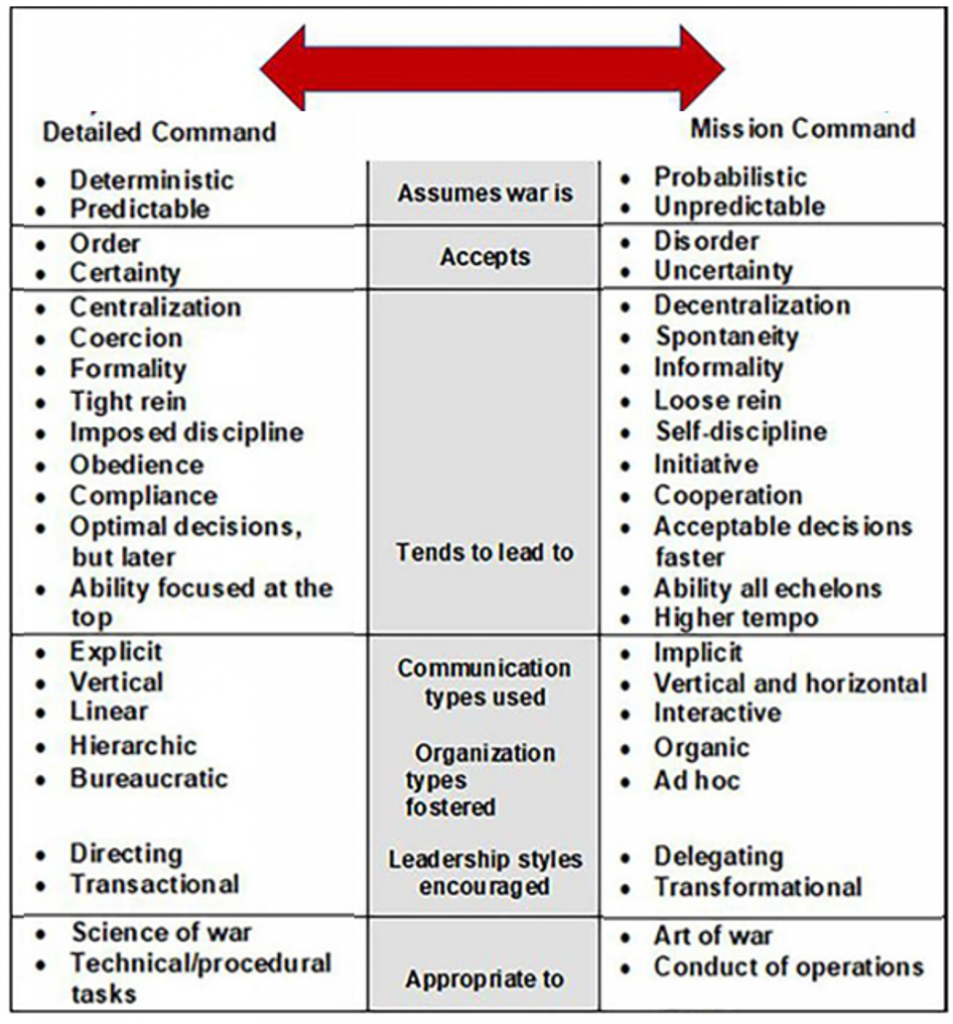

This way of managing is described in detail in the U.S. Army’s manual, Army Doctrine Publication Mission Command 6.0, (2003, D0D) which brilliantly depicts the essence of organizational agility in the table shown in Figure 1. It is called “mission command,” which contrasted with top-down bureaucracy, which it called “detailed command.”

The necessity of agility is obvious on the physical battlefield: soldiers who are not agile are likely to die. The Army Doctrine Publication Mission Command of 2003 noted that “historically, commanders have employed variations of two basic command-and-control concepts: mission command and detailed command. Military regimes have frequently favored detailed command, but an understanding of the nature of war and the patterns of military history point to the advantages of mission command.”

In 2003 in the U.S. military, however, aspiration was not yet reality. As General Stanley McChrystal discovered when he was leading the Joint Task Force in Iraq, the U.S. Army was still deeply embedded in a top-down system of “detailed command.” McChrystal found himself being asked to make decisions and give approvals on matters on which the teams themselves were better placed to make the call.

It was just too slow, even against an under-skilled, under-equipped and under-resourced adversary. “In the time it took to move a plan from creation to approval,” writes McChrystal in his wonderful book, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World (Penguin 2015): “the battlefield for which the plan had been devised had changed. By the time it could be implemented, the plan—however ingenious in its initial design—was often irrelevant. We could not predict where the enemy would strike, and we could not respond fast enough when they did.”

McChrystal saw that the problem wasn’t collaboration within the teams themselves, but rather collaboration between the teams. “The bonds within squads are fundamentally different from those between squads or other units. In the words of one of our SEALs, ‘The squad is the point at which everyone else sucks.”

The teams “had very provincial definitions of purpose: completing a mission or finishing intel analysis, rather than defeating [the enemy]. To each unit, the piece of the war that really mattered was the piece inside their box on the org chart; they were fighting their own fights in their own silos. The specialization that allowed for breathtaking efficiency became a liability in the face of the unpredictability of the real world.”

He saw that the ability to adapt to complexity and continuous unpredictable change was more important than authority and carefully prepared plans. Rapid horizontal communications were more important than vertical consultations and approvals. Teams had to be able to take decisions as needed, without seeking approvals higher up the command.

McChrystal’s approach was to create a “team of teams.” This meant turning the Task Force from a top-down bureaucracy into a network. Each team needed to look beyond its own goals and concerns and see its work as part of the larger mission of the collectivity.

Yet in 2019, there was also a major step backwards at the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Even the aspiration for agility was lacking at upper levels of the DoD. Thus the Mission Command publications of 2003 and 2012 were “superseded” by a new version of Mission Command 6.0, which put the main emphasis on hierarchical command-and-control and top-down bureaucracy.

“Mission Command” was now to be a matter of explicit delegation. Instead of delegation within “the commander’s intent” being the norm, now there had to be explicit delegation from the hierarchy. In effect, “mission command” in 2019 had morphed into the 2003 concept of “detailed command”, a term that curiously is not even mentioned in the Mission Command 6.0 of 2019.

While “mission command” back in 2003 looked like a remarkably far-sighted articulation of 21st century management, “mission command” in 2019 had degenerated into traditional top-down bureaucracy. “Mission command” had essentially been defined out of existence at DoD.

Steps are under way to redress the situation. As Israel re-discovered on October 7, 2023, even the most sophisticated surveillance systems are not immune to surprise.

“Mission command” is not an American invention. Its origins can be traced to Helmuth von Moltke, who was appointed Chief of the Prussian (later German) General Staff in 1857. The dictum that made him famous was: “No plan of operations extends with any degree of certainty beyond the first encounter with the main enemy force.”

Von Moltke can be seen as the godfather of mission command in particular and Agile management more generally. To cope with uncertainty, von Moltke developed and applied the concept of Auftragstaktik (literally, “mission tactics”), a strategic approach stressing decentralized initiative within an overall strategic design. Von Moltke had no time for perfect comprehensive plans. He believed that, beyond calculating the initial mobilization and concentration of forces, leaders at all levels of the force needed to make decisions based on an assessment of a fluid, constantly evolving situation within an overall strategic design.

In the 20th century, von Moltke’s thinking grew steadily more influential in the military and in due course became the formal doctrine of the US Army—at least on the battlefield. The Army in its formal theory of warfare thus contrasts information-based “detailed command” with action-oriented “mission command.”

Mission Command Across The Entire Economy

Yet the issue is broader than the military. With the increasing role of government in our lives, it is vital that governments as a whole operate with genuine organizational agility. In government, as in the private sector, only the Agile will survive.

On December 1, the Drucker Forum declared that “that we cannot continue as we have been doing. We must change what Drucker calls the practice of management, and the discipline of management behind it.” Its five-year initiative to re-frame management could learn much from what we already know from the experience of managing in high uncertainty in the military.

And read also:

The Drucker Forum Proposes Re-framing Management For The 21st Century