The big market moving event of the week was supposed to be the February jobs numbers on Friday (March 10), but there was nary a mention of those numbers in the financial media, upstaged by the second largest, and completely unexpected, bank failure in U.S. history, i.e., Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). The real issue here, and something that will be answered over the next few weeks, is whether or not this was a systemic event, or a one-off.

Because they were a lender to the tech sector, especially tech start-ups, some commentators have concluded that this was a one-off event. In fact, CNBC reported that on Wednesday, SVB was a well-capitalized bank seeking to raise some capital. “Within 48 hours, a panic induced by the very venture capital community that SVB had served and nurtured ended the bank’s 40-year-run.” Relevant here is the level of uninsured deposits. As of 12/31/22, of the $175 billion of deposits, $150 billion were not insured (i.e., over the $250K limit). The run on the deposits appears to be from entities that had deposits that were significantly uninsured. Events like this raise fear in the minds of the public, especially from depositors (usually companies) with large uninsured balances. As a result, we can’t conclude that this won’t happen elsewhere, and we should ask why this bank, whose balance sheet showed significant capital as of 12/31/22, turned out not to have such capital and failed in a matter of hours.

It’s the Bond Portfolio (Stupid!)

When a bank suffers large deposit withdrawals, it must either borrow funds from another bank or the Fed (usually collateralized – normally by the bank’s bond portfolio). If the bank has reached its lending line, it must sell bonds from its portfolio.

Prior to March 2022, bond yields were miniscule and had been so since the end of the Great Recession. The Fed, don’t you know, had kept interest rates near zero until it decided to go on the fastest hiking spree since the early 1980s. Because of the length of time interest rates were low, in order to garner any sort of yield, banks had to buy long duration (time to maturity) bonds. When rates rise, longer duration bonds suffer much higher price depreciation than do shorter ones. And when rates rise spectacularly fast…

We don’t believe that SVB is a loner when it comes to the value of their bond portfolios. It’s been a year since the Fed began hiking. So, the question becomes: If most banks have this bond problem, why aren’t there more bank solvency issues? To protect bank earnings and capital from tumbling when interest rates rise, thirty or so years ago, the accounting profession and the bank regulators set up a “Held to Maturity” classification for bank bond portfolios. Bankers could elect to put bonds in that designation, or into a separate pool called “Available for Sale.” Bonds in the former classification don’t have to be marked to market (i.e., from the purchase price, these bonds amortize or accrete toward the maturity value). The logic is, since they are “Held to Maturity,” market prices do not matter (until they do). Bonds in the “Available for Sale” account are regularly marked to market prices. The one caveat is that a bank cannot not “sell” a single bond from the “Held to Maturity” account. If it did, the entire “Held to Maturity” pool would have to be marked to market.

As noted, because of the miniscule rates from the Great Recession till last March, most of the bonds in that classification were longer-term in nature (because they had some yield when purchased during the Fed’s zero interest rate regime). As rates have dramatically risen over the past year, the market value of those bonds tanked. Clearly, in SVB’s case, the losses in the “Held to Maturity” portfolio were enough to deplete its capital and cause its insolvency.

Likely, most banks would suffer a significant depletion of capital, if not insolvency, if their “Held to Maturity” bond portfolios were marked to market. The truth is, in today’s interest rate world, there is much less capital supporting the bank than what is shown on their balance sheets. Not to fear, like any corporation, the institution survives if it has enough liquidity to continue operations. Nevertheless, this is what poor Fed policy (both keeping interest rate too low for too long, and then spiking them) has done to the banking system. This is what happens when there is a singular goal (2% inflation) that is pursued without regard to the health of the entire system. The danger, today, is that there could be similar such runs on other small/medium sized institutions; all it takes is a rumor. Let’s face it, depositors, especially those with more than $250K in deposits (the FDIC insurance limit) can easily become jittery, especially when a bank like SVB appears to have failed “out of the blue.”

Payrolls

Meanwhile, at 8:30 am on Friday, the jobs numbers for February showed up. While not as hot as January’s, the +311K Seasonally Adjusted number was hotter than expected (market consensus was +225K). Once again, seasonal factors appear to be at play. The Leisure/Hospitality sector led the way (+105K), and, if you can believe it, Retail (+50) and Construction (+24K; despite tanking new home sales and starts) (Hence, our skepticism). The survey showed that the all-important manufacturing sector shed jobs, and the workweek shrunk again (-0.5%), now down in three of the past four months. In addition, overtime fell -3.2% and it has been flat or down in 11 of the last 12 months. So, like January’s jobs numbers, take this one with a grain of salt.

The sister Household Survey showed up with job growth of +177K. However, when this is adjusted to the same basis as the Payroll Survey, it comes out as -106K, a more believable number. The all-important Unemployment Rate (U3), which comes from this survey, rose 0.2 percentage points to 3.6% from 3.4%, as did the broader Unemployment Rate (U6) (to 6.8% from 6.6%). Expect to see these rates rise each month for the foreseeable future.

Layoffs & Unemployment

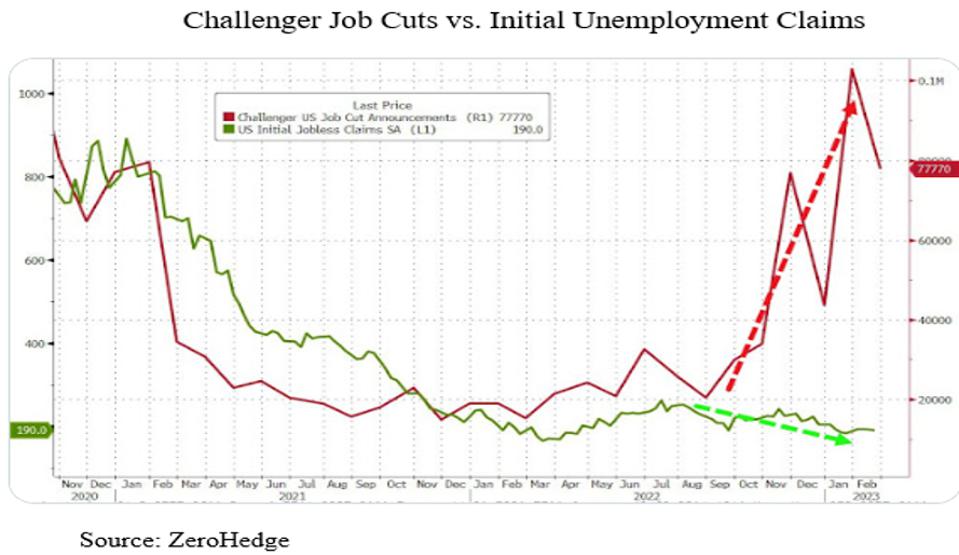

With all the layoff announcements, one would have thought we would have seen a higher U3 by now, and what’s more puzzling is that the weekly unemployment claims have been benign. The chart at the top of this blog shows the rapid rise in the Challenger Job Cuts data vs. the flat line for Initial Unemployment Claims. (Note: the week ended March 4th is not shown on the chart, but that week showed a little spike in claims – Initial Claims +21K; Continuing Claims +69K).

The answer appears to be the lag between layoff announcements and the actual layoffs themselves. And, don’t forget, many layoffs come with extra pay which also might delay unemployment filings. The chart below quantifies that lag. This occurs primarily because of the WARN Act (1980s vintage) which requires employers of more than 100 people to give a 60 day notice (90 days in CA) if the layoff is of 50 people or more. So, the fact that the weekly unemployment claims have not yet spiked is not surprising. They will soon.

JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) has been used by the Fed to justify its rate increases. However, data is now emerging, both in the JOLTS itself and from other data providers, that shows a significant falloff in job openings (see chart). More reasons to expect a rising unemployment rate in the months ahead.

Inflation

The chart below shows the close relationship between the prices paid index of manufacturers in the ISM Survey (with a four-month lead) and the CPI.

Note where prices could go if the current scenario comes close to mimicking any of the last three Recessions. This chart is relevant because we will be getting the next installment of CPI data on Tuesday (March 14).

Final Thoughts

Inflation continues to be the hot topic, not only for the Fed, but also the media. We openly wonder if the SVB insolvency will temper their hawkishness. We believe it should since their policies are ultimately responsible for that failure. But we aren’t holding our breath. In fact, the Fed remains a wild card. Powell’s hawkish testimony before Congress last week had markets concerned that a 50-basis point rate hike was in the offing at the Fed’s March 21-22 meeting. After the nearly overnight failure of SVB, perhaps the Fed Governors will recognize how fragile they have made the financial system, and that, given the rapid rate hikes of the past year, many banks, on a mark to market basis, are likely also insolvent. All it would take is a rumor and a run on any bank’s deposits.

We suspect they will be weighing all of this when they meet. They need to ask themselves: “Will a 25-basis point increase, instead of the 50 that was almost promised by Powell at his Congressional testimony, send the wrong signal to the financial markets which could then possibly move financial conditions toward ease?” (We discuss this Fed dilemma in detail in the appendix below.) On the other hand (although a low odds play), perhaps they will recognize that they have already tightened enough and that inflation will continue to fall if they just let things be. All eyes will be on Tuesday’s CPI number!

(Joshua Barone contributed to this blog)

APPENDIX: The Fed’s Communication Dilemma

For several months, we have discussed the issues surrounding the Fed’s recent “transparency” policy. Prior to this cycle, the Fed and its Governors never communicated their intentions to the markets. The beginning of the new era of “transparency” began in 2012 with the publication of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), which the markets nicknamed “the dot-plot.” So, while the dot-plot has been around for a while, this is its first significant tightening regime.

In today’s world, by communicating its intentions to markets, not only via the dot-plot, but also by the jawboning of various FOMC members, especially in the “tightening” phase of the current cycle, the Fed induced markets to immediately tighten financial conditions to the dot-plot’s terminal interest rate. Markets rapidly moved interest rates higher, and stock and bond prices lower, according to their reading of the Fed’s future “intentions.” The Fed had to do little.

Every tightening cycle comes to an end, and when the economic data began to convince the financial markets that a Recession was brewing, markets began anticipating the Fed’s moves toward less tightening (rate “step-down” and/or “pause”) or toward outright ease (known as a “pivot”). As a result, much to the Fed’s chagrin, through the first month and a half of 2023, markets were easing financial conditions, believing the Fed would first “step-down” rate increases then “pause,” and finally “pivot” to lower rates as Recession evidence mounted. “Step-downs” occurred at its December meeting (raising rates by 50 basis points after four 75 basis point hikes) and then again on February 1 (+25 basis points).

While inflation was retreating as supply chains eased, the Fed clearly isn’t convinced that it’s time to ease financial conditions. Thus, for most of 2023, the Fed has been, in effect, fighting with the market’s move toward beginning the easing process.

Finally, market commentators other than ourselves, have begun to recognize the Fed’s communication dilemma. This past week, Citadel’s founder and CEO, Ken Griffin, made financial news headlines when he said: “Every time they take their foot off the brake, or the market perceives they’re taking their foot off the brake, and the job’s not done, they make their work even harder.” He further commented that the Fed should not make its job harder by confusing markets.

In the Fed’s defense, they have continuously told markets that the rate hiking cycle hasn’t ended nor do they see an end to it just yet, and they have continued to tell markets that they are “data dependent.” Last week, Powell told Congress: “We are not on a pre-set path.” Thus, in our view, their hawkishness is a direct reaction to, what in their view, is the financial markets’ premature easing of financial conditions.

Our our view is that the Fed should go back to the pre-dot-plot era when the Fed insiders never discussed current or future policy. In this scenario, all the market knows is what actions the Fed took. Markets might react, but if the Fed is poker faced, eventually the markets won’t. We think this would make the Fed’s job a lot easier with no chance of “adding to market confusion.”